Cathay Williams / William Cathey: Buffalo Soldier

My father was a freeman, but my mother was a slave, belonging to William Johnson, a wealthy farmer who lived at the time I was born near Independence, Jackson County, Missouri.[1]

So begins the story of Ms. Cathay Williams, the first documented woman to enlist in the U. S. Army. Although her military service did not begin until November 15, 1866, Cathay made her career choice based on her experience with the Union Army, which began in late 1861 when she was “impressed” by Colonel William P. Benton of the 13th Army Corps. She and her family had moved from Independence to Jefferson City, but her master died there and his slaves were evidently cut adrift:

United States soldiers came to Jefferson City they took me and other colored folks with them to Little Rock. Colonel Benton of the 13th army corps was the officer that carried us off. I did not want to go. He wanted me to cook for the officers, but I had always been a house girl and did not know how to cook. [2]

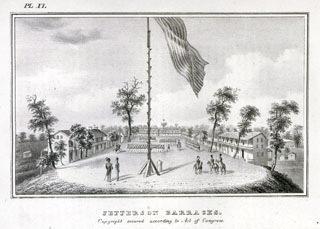

Seventeen-year-old Cathay learned to cook, however, and accompanied the 13th to Pea Ridge. After that battle, the command moved throughout Arkansas and Louisiana, burning cotton. Cathay went with them and was present when rebel gunboats were captured and burned on the Red River at Shreveport during the unsuccessful Red River Campaign.[3] She continued her cooking duties, following the army to New Orleans, then, by way of the Gulf of Mexico, to Savannah, and finally Macon, Georgia. Cathay claims in the interview from which these quotes are taken that she was eventually sent to Washington City, serving as both a cook and washerwoman for General Phillip Sheridan and his staff. Near the end of the war, she ended up at Jefferson Barracks, in eastern Missouri, remaining there until at least April 1865. Jefferson Barracks was the site of a major medical hospital that served soldiers on both sides of the war. In 1862 the Western Sanitary Commission built its largest hospital there as well.[4] Cathay may have stayed in Missouri, cooking and cleaning for one of these institutions until her services were no longer needed. The fact that the regimental headquarters for the 38th U. S. Infantry was located at Jefferson Barracks was probably instrumental in her future.

After the Civil War, employment opportunities were scarce for many African-Americans, especially in the South. Many of them looked to military service, where they could earn not only steady pay but education, health care, and a pension. When Congress reorganized the peacetime regular army in the summer of 1866 it recognized the military merits of black soldiers by authorizing two segregated regiments of black cavalry, the Ninth United States Cavalry and the Tenth United States Cavalry and the 24th, 25th, 38th, 39th, 40th, and 41st Infantry Regiments. Orders were given to transfer the troops to the western war arena, where they would join the army’s fight with the Indians. White officers commanded all of the black regiments at that time. Cathay already had experience living in an army camp and she decided that in order to earn her way, she would enlist. On November 15, 1866, Cathay Williams joined the Army using the name William Cathey. She informed her recruiting officer that she was a 22-year-old cook. He described her as 5′ 9″, with black eyes, black hair and black complexion. An Army surgeon examined Cathey and determined the recruit was “fit for duty,” thus sealing her fate in history as the first documented African-American woman to enlist in the Army, although U.S. Army regulations forbade the enlistment of women until 1948. Cathey was assigned to the 38th U.S. Infantry, became a Buffalo Soldier, and traveled throughout the west with her unit.[5]

The regiment I joined wore the Zouave uniform and only two persons, a cousin and a particular friend, members of the regiment, knew that I was a woman. They never “blowed” on me. They were partly the cause of my joining the army. Another reason was I wanted to make my own living and not be dependent on relations or friends.[6]

The muster rolls reveal that William Cathey was an average soldier. She neither distinguished herself nor disgraced her uniform while in the service. She was never singled out for praise or punishment. She was one of the tallest privates in her company, and she probably never experienced close physical scrutiny during her service, despite hospital visits. From her enlistment date until February 1867, William Cathey was stationed at Jefferson Barracks. Her time there would have been spent in training and getting used to the daily routine of army camp life. It is uncertain, though, just how long she actually was present at the installation. On February 13, Company A of the 38th Infantry was officially organized, and William Cathey, along with 75 other black privates, was mustered into that company. Shortly afterward, she was in an unnamed St. Louis hospital, suffering an undocumented illness. By April 1867 William Cathey and Company A had marched to Fort Riley, Kansas. On April 30, she was described as “ill in quarters,” along with 15 other privates. Because they were sick, their pay was docked 10 dollars per month for three months, so one might presume William Cathey was not malingering. She did not return to duty for two weeks. [7]

The muster rolls reveal that William Cathey was an average soldier. She neither distinguished herself nor disgraced her uniform while in the service. She was never singled out for praise or punishment. She was one of the tallest privates in her company, and she probably never experienced close physical scrutiny during her service, despite hospital visits. From her enlistment date until February 1867, William Cathey was stationed at Jefferson Barracks. Her time there would have been spent in training and getting used to the daily routine of army camp life. It is uncertain, though, just how long she actually was present at the installation. On February 13, Company A of the 38th Infantry was officially organized, and William Cathey, along with 75 other black privates, was mustered into that company. Shortly afterward, she was in an unnamed St. Louis hospital, suffering an undocumented illness. By April 1867 William Cathey and Company A had marched to Fort Riley, Kansas. On April 30, she was described as “ill in quarters,” along with 15 other privates. Because they were sick, their pay was docked 10 dollars per month for three months, so one might presume William Cathey was not malingering. She did not return to duty for two weeks. [7]

On July 20, 1867, Company A arrived at Fort Union, New Mexico, after a march of 536 miles. On September 7, they began the march to Fort Cummings, New Mexico, arriving October 1. The unit was stationed there for eight months. When the company was not on the march, the privates did garrison duty, drilled and trained, and went scouting for signs of hostile Native Americans. William Cathey participated in her share of the obligations facing Company A. There is no record that the company ever engaged the enemy or saw any form of direct combat during this time.[8]

I was as that paper says, I was never put in the guard house, no bayonet was ever put to my back. I carried my musket and did guard and other duties while in the army,[9]

In January 1868, after about eight months off the sick list, her health began deteriorating. On the 27th of that month, she was admitted to the post hospital at Fort Cummings, citing rheumatism. She returned to duty three days later. On March 20, she went back to the hospital with the same complaint. Again, she returned to duty within three days. On June 6, the company marched forty-seven miles to Fort Bayard, New Mexico. This was the last fort at which William Cathey lived during her army stint. On July 13, she was admitted to the hospital at Fort Bayard, and diagnosed with neuralgia.* She did not report back to duty for a month. This was the last recorded medical treatment of William Cathey while in the military. The fact that five hospital visits failed to reveal that William Cathey was a woman raises questions about the quality of medical care available to the soldiers of the U.S. Army, or at least to the African-American soldiers. Clearly, she never fully undressed during her hospital stays. Perhaps she objected to any potentially intrusive procedures out of fear of discovery. There is no record of the treatment given her at the hospitals. There is every indication that whatever treatments she received, they did not work.

On October 14, 1868, William Cathey and two other privates in Company A, 38th Infantry were discharged at Ft. Bayard on a surgeon’s certificate of disability. William Cathey’s certificate included statements from both the captain of her company and the post’s assistant surgeon. The captain’s statement read that Cathey had been under his command since May 20, 1867:

. . . and has been since feeble both physically and mentally, and much of the time quite unfit for duty. The origin of his infirmities is unknown to me. He is of . . . a feeble habit. He is continually on sick report without benefit. He is unable to do military duty. . . . This condition dates prior to enlistment.[10]

Cathay Williams, also known as William Cathey, served her country for just over two years. The interview she gave to the St. Louis Daily Times in 1876 gives us the only clues as to what happened to her after leaving the service:

After leaving the army I went to Pueblo, Colorado, where I made money by cooking and washing. I got married while there, but my husband was no account. He stole my watch and chain, a hundred dollars in money and my team of horses and wagon. I had him arrested and put in jail, and then I came here. I like this town. I know all the good people here, and I expect to get rich yet. I have not got my land warrant. I thought I would wait till the railroad came and then take my land near the depot. Grant owns all this land around here, and it won’t cost me anything. I shall never live in the states again. You see I’ve got a good sewing machine and I get washing to do and clothes to make. I want to get along and not be a burden to my friends or relatives.[11]

At some point in late 1889 or early 1890, Cathay Williams was hospitalized in Trinidad, Colorado for nearly a year and a half. She filed in June 1891 for an invalid pension based upon her military service. Her application brought to light the fact that an African-American woman had served in the Regular Army. Her original application for the pension, sworn before the local County Clerk gave her age as forty-one. She stated that she was one and the same with the William Cathey who served as a private in Company A, 38th U.S. Infantry for just under two full years. She claimed in her application that she was suffering deafness, contracted in the army. She also referred to her rheumatism and neuralgia. She declared eligibility for an invalid pension because she could no longer sustain herself by manual labor. On September 9, 1891, a medical doctor, in Trinidad, employed by the Pension Bureau, examined Cathay Williams. The doctor described her as 5′ 7″, 160 pounds, large, stout, and forty-nine years old. He reported that she could hear a conversation and therefore was not deaf. He also reported no physical changes in her joints, muscles, or tendons indicating rheumatism or neuralgia. Most horrifying, the doctor reported that all her toes on both feet had been amputated, and she could only walk with the aid of a crutch. This did not happen during her time in service, however.[12]

In February 1892 the Pension Bureau rejected her claim for an Invalid Pension. After this, Cathay Williams disappears from the pages of history. She is not listed in the 1900 Federal Census, so from this may be surmised that she probably died between 1892 and 1900, at the age of eighty-two. A pioneer even if she did not know it, Cathay Williams was the first female Buffalo Soldier. This improbable, independent, strong black woman should not be overlooked. In July 2016, a bronze bust of Cathay Williams, surrounded by a small rose garden, was unveiled outside the Richard Allen Cultural Center in Leavenworth, Kansas.

General Barbara Lynne Owens, one of two black female generals currently serving in the Army Reserve, said she learned about Williams “a long time ago.” Owens called her an early trailblazer who set the path for all black female soldiers who have followed, saying:

If she had not done what she did, I would not be standing here today.[13]

* * *

[1] St. Louis Daily Times, January 2, 1876 [online version available at

http://www.buffalosoldier.net/CathayWilliamsFemaleBuffaloSoldierWithDocuments.ht (accessed February 14, 2018)].

[2] Ibid

[3] United States Government Printing Office, Congressional Serial Set, (reprint, Ulan Press, 2012), 270-273. [online version available at https://books.google.com/books?id=PIQZAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA273&lpg=PA273&dq=rebel+gunboats+burned+near+shreveport&source=bl&ots=nhuQqRtlHG&sig=bULfdTAw0z7u2P9a6lt_vT4IXRk&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjy44TD-ajZAhVpyoMKHSeVAocQ6AEINTAE#v=onepage&q=rebel%20gunboats%20burned%20near%20shreveport&f=false (accessed February 13, 2018)].

[4] Jefferson Barracks Museums, St. Louis County, Missouri Parks and Recreation. [online version available at https://www.stlouisco.com/ParksandRecreation/ParkPages/JeffersonBarracks/JeffersonBarracksMuseums (accessed February 12, 2018)].

[5] http://www.amazingwomeninhistory.com/cathay-williams/ and http://web.archive.org/web/20080616094119/http://www.goarmy.com/bhm/profiles_williams.jsp (accessed February 10, 2018).

[6] St. Louis Daily Times, January 2, 1876 [online version available at

http://www.buffalosoldier.net/CathayWilliamsFemaleBuffaloSoldierWithDocuments.ht (accessed February 14, 2018)].

[7] http://www.buffalosoldier.net/CathayWilliamsFemaleBuffaloSoldierWithDocuments.htm

[8] Ibid.

[9] St. Louis Daily Times, January 2, 1876 [online version available at

http://www.buffalosoldier.net/CathayWilliamsFemaleBuffaloSoldierWithDocuments.ht (accessed February 14, 2018)].

[10] http://www.buffalosoldier.net/CathayWilliamsFemaleBuffaloSoldierWithDocuments.htm

[11] St. Louis Daily Times, January 2, 1876 [online version available at

http://www.buffalosoldier.net/CathayWilliamsFemaleBuffaloSoldierWithDocuments.ht (accessed February 14, 2018)].

[12] http://www.buffalosoldier.net/CathayWilliamsFemaleBuffaloSoldierWithDocuments.htm (accessed February 14, 2018)].

[13] Miranda Davis, “Monument to female Buffalo Soldier is dedicated in Leavenworth,” The Kansas City Star, July 22, 2016. [online version available at http://www.kansascity.com/news/local/article91412232.html (accessed February 13, 2018)].

Excellent piece. Thank you.

You are most welcome. Thanks for reading ECW.

What a fascinating story. Frontier service after the war was pretty awful for all the Army, but especially for the Buffalo Soldiers. I am glad she has been honored, though like Henry Johnson of WWI fame, the recognition comes very late.

I agree. We ECW writers were tasked to find some uncommon examples of African-American contributions to the war effort, and I thought Cathay was an excellent example.

I find it hard to believe that she was ‘examined’ by a doctor when she enlisted and wasn’t ‘discovered’ to be a woman. Was the service so desperate for bodies that the only real criteria to consider was whether the recruit in question was breathing?

Pretty much yes. There were a fair number (in the hundreds) of women who were sworn into federal service (at least in the Union Army) that were enlisted into service and not discovered to have been of an unapproved sex until they were either wounded or gave birth.

If you would like to do some reading, I can give you some sources.

By all means Rosemary. I appreciate that..

Apparently breathing was just about all that mattered. I can imagine not dropping trou, but not even a chest exam for the breathing part? But–we are finding more and more examples of women masking their gender and serving. I think it says more about the medical world than anything else. Thanks for reading.

Thank you for writing this article. You are very busy preparing for presentations thoughout California and you are finishing your book on Elmer Ellsworth. Im looking forward to attending your presentation in Redlands, California in March. It is great to hear of great African-American heroes of the United States Civil War and that era.

It takes a village! Thanks for your help.

A remarkable story, outside of the mainstream narratives about the USCT and Buffalo Soldiers. Thanks for digging around to find the sources you used, putting this together and sharing it with all of us.

Google her up and look at the variety of images. We didn’t use any here because they are “art” and belong to someone else, but they are fascinating. Thanks for your thoughtful comment.

The Difficult Truth related to the “Cathy Williams” Story

From Dr. Leo Oliva:

Because the story of a female buffalo soldier has been out there for a long time and at least 3 biographies have pieced together a story based on undocumented claims, many people will never give up the fiction for the fact.

There are two documents that claim William Cathey was a woman, the Jan. 2, 1876 St. Louis newspaper article quoting Cathey Williams (it is amazing how the detailed story is based on one primary source) and the 1880 census in which Cathey Williams is identified as black, female, married, living alone, giving birthplace of parents and herself as New Mexico.

There is not one mention in any of the military records that William Cathey was identified as a woman.

William Cathey was examined by a military surgeon on enlistment and identified as “he” throughout.

Private William Cathey spent several weeks in at least 3 and probably 4 or more military hospitals. It would be impossible to hide true identity there, and all records record “he.”

The discharge papers never mention female even though the 1876 newspaper article quoting Cathey Williams states she allowed herself to be identified as a woman and was discharged.

The discharge is a medical discharge and includes a statement that medical conditions predated enlistment.

Thus, when William Cathey, as a man, sought a military pension, it was denied because conditions predated enlistment.

Again, no mention in any of those records of Cathey being a woman.

There is no corroborating documentation of Cathey Williams serving with the 8th Indiana Infantry during the Civil War as a female slave taken as contraband.

William Cathey may well have been a servant in the Civil War army, but so far no records have confirmed that.

The photo that some biographers claim shows Cathey Williams serving Gen. Phil Sheridan in the field during the Civil War has no documentation of the identity of that person who cl(e)arly appears to be a man.

The date on the photo is in 1863, but the 8th Indiana Infantry did not arrive in Virginia until 1864.

The photo of Cathey Williams or her mother reportedly taken in the early 1870s at the Abraham Lincoln Orphanage for Black Children in Pueblo CO is suspect.

The Lincoln Orphanage was founded there in 1906. Williams’s mother would have been 81 years old at the time.

Williams was living in the Pueblo Insane Asylum in 1906, having been adjudged insane in 1897. The fantastic story of a female buffalo soldier is based on one document, the newspaper article in 1876.

The military records of William Cathey’s service in Co. A, 38th U.S. Infantry, never mention woman or female, but the records do show Williams was in military hospitals at St. Louis, Fort Riley, and Fort Bayard, and may have been in hospitals at Fort Leavenworth, Fort Harker, Fort Union, and Fort Cummings.

There have been or now are markers about Cathey Williams, female Buffalo Soldier in New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas (including the statue at Leavenworth), Virginia, and Florida.

There is no documented image of William Cathey, but there are about a dozen artists’ speculative images. The story of William Cathey should be a lesson in historical research: never base a story on a single document for which there is no corroboration.

Unfortunately, the fiction will continue regardless of the absence of documentation.

I think the documentation of a man who served in the military and became a transwoman who claimed to have been a female Buffalo Soldier is a story that should be told with plenty of documentation.

I continue to seek more information and attempt to tell the true story. If I can be of any help, let me know.

I challenge anyone to find a document in William Cathey’s military record that mentions that Williams was a woman or female.

From Dr. Frank N. Schubert

Cathay Williams/William Cathay

Grant, Kay. “Working Undercover: An unusual Buffalo Soldier kept an extraordinary secret,” New Mexico Magazine, 85(June 2007), pp. 52-55.

Buffalo Soldier “a nickname given to the all-black regiments by Indians because of its members thick curly black hair and strong fighting abilities.” (KGrant, p. 52.)

medical exams were cursory: could recruit march and shoot? Then, OK, fit for duty. (KGrant, p. 52.)

Melodie Lynn Clark Thompson: reenactor who frequently portrays Cathay Williams in her play “Only a Woman” (KGrant, p. 53.)

This was the opening event for Women’s History Month, Smithsonian Museum of American History, 1 Mary 2002, according to Blue Bulletin, 17 (19 Feb 2002), published for SI staff for office of public affairs, SI.

“Williams” contracted cholera on long march to Ft Union, NM [not small pox] (KGrant, p. 54.)

“…performed with diligence and always to the best of her ability.” (KGrant, p. 55.) (Not substantiated with documentation wwg)

Kay Grant. “This Buffalo Soldier Had a Secret Life That Must Have Been Hard to Conceal,” Wild West, 25 (April 2013), pp. 22-23.

Appears to be reprise of earlier article: lived in fear of discovery, performed same duties as others, showed no signs of femininity during long march, marched and performed duties conscientiously and stayed out of trouble, never in guard house

Army provided black men with inadequate supplies and equipment. (This is an old story that even William Leckie suggested that he would remove from his book, “The Buffalo Soldiers” if he had had the opportunity to revise it another time (personal conversation between Bill Leckie and Bill Gwaltney)

Swain, Charles B. and Kathleen Linder. “The Woman Who Was a Buffalo Soldier,” 2 pp., in A Celebration of Black Cowboys, Buffalo Soldiers and Black Pioneers of the American West, Charles B. Swain, ed. (NP: np, nd), 14 pp, on sale, State Museum of New York, Albany, 1998.

Swain identified as Minorities Historian of Green County (Athens), New York; folklorist in area since 1970s

Swain as of 1999 gave Harriet Tubman tours, lists this pamphlet among “several” books that he has written, claims to be only minorities historian of a US county http:// http://www.hopefarm.com/harriet.htm#Charles%20B.%20Swain, accessed 20 Nov 2007.

Swain paints portrait of hero unsupported by evidence:

“….saved 2 comrades from being shot by outlaws, for which “she was given an award for bravery.”

“ambushed by Indians while building a road, she shot 3, “one of whom was about to kill her!”

“…a truly great African American woman, one of the founders of the West. She is one of the very few African-American women who served with the Buffalo Soldiers. Even as she served very courageously while as a Buffalo Soldier, there is nothing written in history about her life after she left the Army. History would truly be benefitted if more details of her post-Army life were to be revealed.”

in Swain’s hands, this indifferent soldier morphed into a Pauline Bunyan of the post-CW west

Cynthia Savage, “Cathay Williams, Black Woman Soldier, 1886-1887 [sic],” oral presentation to West Texas Historical Society, 11 April 1997,” accessed and printed from http://www.female buffalosoldier.org/cynthiasavage_pg1.html, 17 February 2001.

“in company with discipline problems, she did her duty, avoided guard house “

Michelle Frempong, “William Cathay–a one-of-a-kind Buffalo Soldier…,” Bronze Warrior, 1 (March 2001).

Buffalo Soldier: “…a name of honor and respect given to them by the plains Indians due to their demonstrated strength, courage and perseverance as soldiers in combat, as well as their ethnic physical trait of short, black and curly hair.” (No evidence provided)

“unlike mil doctors, who were not held to strict standards in appraising the gender of prospective recruits, corrections officers at DC jail were held to high standard

strip-searched a woman named Virginia Grace Soto, failed to realize she was in fact she, assigned her to male detention unit, where allowed to shower with male inmates.”

she came in contact with 9 jail employees, 3 of whom (got) fired

(David Nakamura, “D.C. to Fire 3 Over Woman’s Detention as a Man,” Washington Post, Thur, 16 Aug 2007, p. B1; David Nakamura, “Union Criticizes 3 Firings After Inmate Mis-Up,” Washington Post, Tue, 21 Aug 2007, p. B4)

La Tanya J. Maxey, “First Female Buffalo Soldier,” The Messenger, May 2003, pp. 8-9, 23, 27.

“good upbringing, as a house servant on a plantation in MO: “…the influences of the Black culture on the plantation helped to instill in her a sense of honor, integrity and strength, which would serve her well in the years to come,” especially when she lied about her sex to join the army, I suppose.” (Maxey, p. 8)

“…Cathay left a lasting impact on America. Cathay was a beacon of light during one of this nation’s darkest times. Although she never had any children of her own, she left a lasting legacy.” (Maxey, p. 27)

Philip Thomas Tucker, Cathy Williams: From Slave to Female Buffalo Soldier (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002).

I read manuscript and found it full of suppositions, assumptions, and assertions.

Sarah Eppler Janda, reviewer on H-Minerva (May 2002), agreed:

“…Tucker fails to demonstrate what was so noteworthy about this one woman who pretended to be sick in order to avoid service that she herself willingly entered.”

“,…sources do not support his claim that she was a trailblazer and she served as an inspiration, “

“H-Net Reviews in the Humanities and Social Sciences,” http://www2.h-net.msu.edu/reviews, accessed and printed 5 Sep 2002.

“New Mexico Women Historical marker Initiative gives reception to thank supporters at Governor’s Mansion.” Artesia (New Mexico) Daily Press, 29 Jul 2007.

1st of 4 roadside markers honoring notable women in NM history dedicated Saturday, 8 December 2007, in Santa Fe: next 21 include “Cathay Williams of Luna County.”

“Sisters of Loretto opened first New Mexico School,” Santa Fe New Mexican, Sunday, 9 Dec 3007.

Cathay Williams

In a tiny shotgun cabin

Martha’s baby girl was born.

A baby born to slavery

That no one could forewarn.

Cathay Williams was determined

And never was deterred

As she began her life as a house girl

Being seen but never heard.

Then the Civil War broke out

And the Union soldiers came

And taking Cathay with them

Her life would never be the same.

Cathay learned the ways of military life

And became an accomplished cook.

She was sent to General Sheridan

A job she proudly undertook.

Then the Civil War was ended

And Cathay was finally free

And in seeking out her freedom,

She found her place in history.

Her own way she needed to make

And a burden to no one be

So as a Buffalo Soldier she joined up

In the 38th U. S. Infantry.

Cathay Williams became William Cathay

And no one was to know

The secret of her identity

As a soldier she did grow.

The troops moved west to Ft. Cummings

To keep the Apache at bay.

There were one hundred and one enlisted men

And among them was William Cathay.

After two years as a soldier

In the 38th Company A

William went to see the doctor

And her secret came out that day

Discharged as a Buffalo Soldier

Cathay did her very best

As she continued to make her way

In this land they called the West.

Because of her illegal enlistment

Her pension passed her by

But she picked herself up and moved on

And never questioned why.

Life ended for Cathay Williams

At the age of eighty-two

She lived a long independent life

A life that was tried but true.

A salute to Cathay Williams

The hero of this rhyme

A special woman of the west

A legend in her time.

© July 1999, Linda Kirkpatrick

found by Irene Schubert at:

http://www.buffalosoldier.net/CathayWilliamsFemaleBuffaloSoldierWithDocuments.htm

“Official Scenic Historic Marker,” Cathay Williams, nr Deming, on NM Rte. 26, at milepost 10.2,

“Born into slavery, Cathay was liberated in 1861 and worked as a cook for the Union army during the Civil War. In 1866 she enlisted in the U.S. Army as Private William Cathay serving with the Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Cummings and Fort Bayard until 1868.

“She is the only documented woman to serve as an enlisted soldier in the regular U.S. Army during the 19th Century.”

http://www.hmdb,org/map.asp?markers=38211, accessed 9 June 2011.

Information from Dr. John Langellier redacted until a publication date in the near future.