“Whipt ’em Everytime”: The Poorly Titled Diary of Bartlett Yancey Malone

Researching the VI Corps of the Union Army of the Potomac has also made me quite familiar with Richard Hoke’s brigade of North Carolina infantry. These Tarheel regiments–the 6th, 21st, 54th, and 57th–frequently found themselves matched up against those whose blue kepis were adorned with the Greek Cross. At Second Fredericksburg, Rappahannock Station, and throughout the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, the VI Corps soldiers got the best of the North Carolinians. When writing about the first two battles, I can’t help but roll my eyes when I have to cite “Whipt ’em Everytime” while providing the Confederate perspective.

Researching the VI Corps of the Union Army of the Potomac has also made me quite familiar with Richard Hoke’s brigade of North Carolina infantry. These Tarheel regiments–the 6th, 21st, 54th, and 57th–frequently found themselves matched up against those whose blue kepis were adorned with the Greek Cross. At Second Fredericksburg, Rappahannock Station, and throughout the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, the VI Corps soldiers got the best of the North Carolinians. When writing about the first two battles, I can’t help but roll my eyes when I have to cite “Whipt ’em Everytime” while providing the Confederate perspective.

Bartlett Yancey Malone was born in 1838 in Caswell County, North Carolina. Upon the outbreak of the Civil War he joined the Caswell Boys Company, which was soon attached to the 6th North Carolina Infantry. Malone rose to the rank of sergeant and remained on the rolls through March 1865. He kept a diary from 1862 to 1865 that wound up in the special collections at the University of North Carolina.

William Whatley Pierson, Jr. was a fixture at Chapel Hill, as an instructor, professor, and finally a dean of the graduate school. In 1919, Pierson first published Malone’s memoirs in volume 16, number 2 of the North Carolina Historical Society’s James Sprunt Historical Publications. Pierson simply titled his typescript “The Diary of Bartlett Yancey Malone” for the academic journal.

Forty years later, as Civil War publications increased leading up to the centennial, Malone’s journal reached a wider audience. McCowat-Mercer Press (Jackson, TN) published Pierson’s annotated version of the diary in 1960. Needing a catchier name to draw sales, either Pierson or the publisher decided to title the book Whipt ’em Everytime: The Diary of Bartlett Yancey Malone, Co. H, 6th N.C. Regiment. Malone’s diary entry on May 9, 1862 provided the basis for the title. While retreating up the Virginia peninsula from Yorktown to Richmond, Malone wrote:

And the 9 day we rested untell about 12 oclock and then started out on our march again and befour we had gone a mile we hird that our Cavalry was attacked by the Yankees And then we had to stop and wate a while but we whipt them like we aulways do.

However that brief excerpt is not indicative of the style of Malone’s journal. The desire for catchiness unfortunately forced a braggadocious title onto the North Carolinian’s candid diary entries. As Pierson wrote in 1919:

Mr. Malone performed no extraordinary feat of heroism, at least none such was recorded; he participated with individual distinction in no political movement of importance; he played no role which would cause historians to single him out for particular notice. His diary is reproduced here as a document of human interest which reveals, with much quaintness of expression, the thoughts of a simple soldier of the ranks – the thoughts, it is to be presumed, of a mass of men, which have oftentimes been inarticulate.

There is a frankness about this diary that conveys inevitably, I believe, the conviction of sincerity. And there is a lack of emotion – as when in remarking on an event which, we are told, caused the soldiers great grief, the death of Stonewall Jackson, he merely said, “And General Jackson died to-day, which is the 10th day of May” – an absence of bitterness and of complaints which, considering the provocation of circumstances, make the diary of almost as much interest because of these omissions as because of what is included.

My interest in the VI Corps was first piqued while studying what was happening around Fredericksburg at the time of Jackson’s wounding. As an intern in 2010 with Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park I wanted to better understand the successful charge against Marye’s Heights on May 3, 1863, and the fighting that afternoon and the following morning around Salem Church. I soon noticed a trend among the VI Corps battles that defied our conventional understanding of the Civil War. The corps had mastered the frontal assault–the tactic that seemed suicidal to consider.

After successfully breaching the stone wall, whose defense depended more on the memory of the December bloodbath than the two living Mississippi companies who manned the sunken road, the corps slowly pushed west along the Orange Turnpike to Joseph Hooker’s aid at Chancellorsville. Their progress was halted at Salem Church that afternoon, by which time Hooker had entirely given up on the prospects of a successful campaign.

John Sedgwick, commanding the VI Corps, received conflicting orders to both come to Hooker’s assistance by way of the turnpike and by crossing the river and to remain in place. Sedgwick ultimately settled into position with both flanks anchored on the river. In doing so he lost his connection with the two brigades of John Gibbon’s II Corps division who remained in Fredericksburg. Robert E. Lee sought to exploit Sedgwick’s isolation and further divided his own army, sending brigades east from Chancellorsville to try and destroy the VI Corps.

While the VI Corps was storming Marye’s Heights on May 3rd, Hoke’s brigade (with the majority of Jubal Early’s division) remained on the hills stretching southeast toward Hamilton’s Crossing. They retreated south to rally those who escaped Marye’s Heights and found that Sedgwick declined to pursue in that direction. Malone wrote, “for some cause we we all ordered to fall back about a half of a mile to our last breast works.” With the VI Corps’ attention drawn to the presumed attack from the direction of Chancellorsville, Early thus had an ideal position from which to attack the next morning.

The attack along the turnpike never materialized on May 4, causing Early to attack alone. Though he succeeded in regaining Marye’s Heights without contest, the VI Corps stood firm in their U-shaped position, shuffling reinforcements to the threatened sector. The Confederate attack overlapped itself before reaching the target, producing confusion and further dooming any chance of success. Cut off from a direct connection with the rest of the Union army and confused by Hooker’s conflicting orders, Sedgwick pulled the corps back across the Rappahannock at Banks Ford.

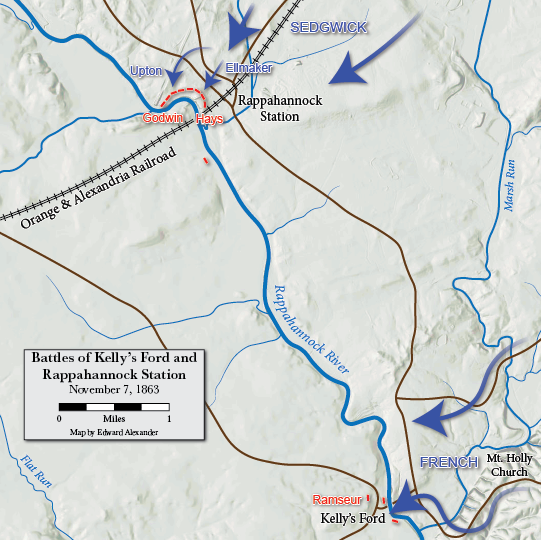

The VI Corps brought up the rear of the Union march into Pennsylvania and saw little combat at Gettysburg. Their next notable engagement occurred on November 7, 1863 at Rappahannock Station. After failing to outflank the Army of the Potomac during the offensive that resulted in the October 14th battle of Bristoe Station, Robert E. Lee settled into winter camp below the Rappahannock River. He left a pontoon crossing and bridgehead just upstream from the destroyed Orange & Alexandria Railroad bridge over the Rappahannock.

Lee believed that active campaigning had ended for the year but planned to utilize the Rappahannock Station crossing in case George Meade wanted to continue operations. Lee expected that if Meade did advance, the Union general would maneuver to Kelly’s Ford, downstream from Rappahannock Station. Lee would then cross a portion of his army at Rappahannock Station to attack Meade’s column as it marched. Meade instead divided his army into two and sent it forward on November 7th. The I, II, and III Corps marched for Kelly’s Ford while the V and VI advanced straight toward Rappahannock Station.

Harry Hays’s Louisiana brigade manned the fortified bridgehead. The sudden appearance of the Union forces came as a surprise but the Confederates chose to reinforce rather than withdraw. Three regiments from Hoke’s brigade crossed the pontoon to reinforce Hays. Hoke was absent and the 21st N.C. was back in its native state at the time. Colonel Archibald Godwin assumed command of the 6th, 54th, and 57th, and placed them among Hays’s regiments. Malone wrote:

The 7th about 2 o’clock in the eavning orders came to fall in with armes in a moment that the enemy was atvancen, Then we was doubbelquicked down to the river (which was about 5 miles) and crost and formed a line of battel in our works and the yanks was playing on ous with thir Artillery & thir skirmishers a fyring into ous as we formed fyring was kept up then with the Skirmishers untell dark.

The VI Corps drove Hays’s skirmishers back into the entrenched bridgehead. The Confederates thought that the late hour meant the engagement had ended but Union division commander David Russell sent brigades under Peter Ellmaker and Emory Upton to storm Hays and Godwin’s position.

Ellmaker attacked first, the 6th Maine and 5th Wisconsin overrunning the Louisiana Guard Artillery. Godwin shifted his regiments out of the fortifications to counterattack the two Union regiments but Ellmaker brought the 49th and 119th Pennsylvania forward at the same time. While combat continued at close range, Upton’s brigade formed to the northwest. As darkness closed around the still-contested position, Upton sent the 5th Maine and 121st New York forward. They stormed over the works whose numbers had been reduced by Godwin’s counterattack toward Ellmaker. Upton’s two regiments swept the line in both directions while several companies pushed onward to cut the Confederates off from retreating across the pontoon.

Hays managed to escape across the bridge, and some Confederates swam the river to avoid capture, but the battle’s result was among the most lopsided of the war. In a direct attack against two fortified Confederate brigades, six VI Corps regiments successfully stormed the position and captured nearly the entire garrison.

Barlett Malone was among those captured. “About dark the yanks charged on the Louisianna Bregaid which was clost to the Bridg and broke thir lines and got to the Bridge we was then cutoff and had to Surender,” he wrote. Malone was sent to Point Lookout where he remained until paroled in late February 1865.

It thus seems a bit disingenuous to imply that Malone and the 6th North Carolina Infantry indeed “whipt ’em everytime” but I’m not surprised to see it at the centennial of the war. Unfortunately that sentiment continues through this day. Despite evidence to the contrary, many visitors with whom I interact are still convinced that no one in the Union army knew how to fight or were willing to do so. Perhaps if I ever compile the various VI Corps frontal attacks into one book I can borrow a name for the title…

Just saw over on our partner site–Emerging Revolutionary War–a post providing the inspiration for the title “A Single Blow” of their recent book on Lexington and Concord.

https://emergingrevolutionarywar.org/2018/04/19/a-title/

As Jack Webb used to say, “Just the facts”! Historians, guides, rangers, docents, etc. should hug the middle of the interpretative road. I’ve worked for history museums in both NC & VA. I could provide plenty of examples of poor Union leadership and ineffectual fighting over a long four years. The NC veteran who wrote this book is certainly entitled to name it anything he likes. If you’d like to point out book titles that aren’t supported by facts – try “War of the Rebellion”.

Thanks for commenting.

Neither the soldier-diarist Malone nor editor Pierson called the original manuscript or the first publication “Whipt em Everytime.” Malone died in 1890, three decades before Pierson’s first published the diary. It was only during the centennial of the war when either an older Pierson or the publisher wanted a catchier name for the reprint. This was also at a time when the popular opinion of the war was that the south kept whipping the Yankees until there were just too many to whip. This does not line up with how Union armies and generals actually won the war but I still hear this opinion nearly every day as a public historian.

My contention with the title is its woeful inaccuracy, even in misrepresenting the theme of Malone’s original diary entries. As Pierson noted, Malone wrote humbly and reserved, not arrogant and boastful.

But what I found humorous about the title is how it completely misrepresents Malone and the 6th’s war record, particularly at the most influential battle for Malone–Rappahannock Station–after which he will remain sidelined for the next fifteen months. It pitted two brigades attacking two entrenched brigades and yet was one of the most lopsided northern victories of the war. Malone and the bulk of Hays and Godwin’s men were captured. The defining moment of Malone’s service is a battle that highlights northern leadership and fighting ability. Yet the publisher nonetheless chose the title “Whipt ’em Everytime” and I’ll chuckle every time I cite it when writing about Rappahannock Station.

“War as I remember It”, the author of the book had a long time to think about his fighting in a P.O.W. camp. The author had his “readers” who he wanted to focus on and influence. He could sit on his porch in his rocking chair, like Granny, and hold his rifle at his side saying to everyone, “I wipt em every time”. Its more inspiring then, “We fought hard and lost”.