William Freret: From Folly to War to Success

William Freret Jr. enjoyed one of the most unusual careers during the Civil War, including brief service in the Washington Artillery. He also had one of the most successful postbellum professional careers; by the time of his death, he was one of the elite architects of New Orleans, a city considered one of the architectural gems of the world.

Freret was born in 1833 to New Orleans mayor William Freret and Fanny Salkeld. He studied engineering in Britain and returned to New Orleans to become an architect, becoming a pioneer in the use of cast iron to create taller buildings in the city. The 1850s was the heyday of the city’s growth and wealth, and the rich showed off their wealth by commissioning grand homes. However, architects were not paid much, and it was a busy life. Freret used what money he had to build a set of speculation homes in the Garden District, hoping to attract wealthy buyers. They were finished in 1861, but the onset of war led to an exodus of Garden District residents, many of which were unionists. Freret was ruined and the homes are still today called “Freret’s Folly.”

Following his folly, the Louisiana militia expanded in order to repel an invasion. Freret joined the Orleans Light Horse in November 1861. His brother Frederick joined the unit in March 1862 and eventually made sergeant. When General P.G.T. Beauregard called for troops after the fall of Fort Donelson, the Orleans Light Horse volunteered to be sent north to Corinth. At Shiloh, they acted as escort and scouts to Major General Leonidas Polk.

Freret’s stint in the cavalry was short. On May 5, he joined the 5th Company Washington Artillery, an elite New Orleans unit. Captain Cuthbert H. Slocomb took him in, and Freret was supposed to make maps. However, on July 25 his time in the artillery ended when he was transferred to the engineering corps. The next month he joined the staff of Major General Edmund Kirby Smith, accompanying him on the Kentucky offensive. In September, Smith asked to have Freret promoted to lieutenant. Smith also requested that Freret be released from the rolls of the Washington Artillery.

By January 1863, Freret served as acting assistant engineer. He moved to the Trans-Mississippi with Smith but became ill in the summer. Promoted to captain in 1864, he worked as the acting chief of engineer at Shreveport. Smith was in the habit of promoting men without waiting on Richmond’s blessing, and he made Freret a Lieutenant Colonel.

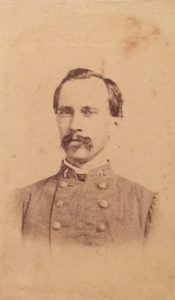

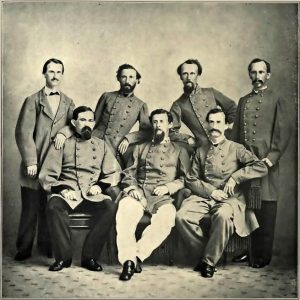

Freret became ill in 1865. He did not accompany Smith to Texas, but instead took his parole. Along with some other officers, he had his picture taken in Shreveport, making it one of the last photographs of active Confederate officers in uniform. Freret’s war career was unusual. He served in the cavalry, artillery, engineers, and as a staff officer. Few men had enjoyed such a wide number of experiences and responsibilities.

Compared to many of his contemporaries, Freret had an excellent postbellum career. He became one of Louisiana’s premier architects. One on 2504 Prytania Street became the New Orleans Women’s Opera Guild in 1965. He used the unusual Swiss Chalet style to build a home for Senator James Eustis. Both are today fixtures on Garden District tours.

Freret was a Democrat and benefited from the election of Grover Cleveland. In 1885, William was appointed the Head of the Office of the Supervising Architect, a sub-office of the United States Treasury that was in charge of building government buildings from 1852-1939. From this position, he and his staff designed post offices throughout America, often in the Romanesque Style. With the victory of Benjamin Harrison in 1888, Freret lost his government job but left his mark on the national landscape.

Of all his buildings, though, Freret’s most impressive was his work on the Louisiana State Capital. The building had been burned by Union troops, and Freret was tasked with keeping its unusual Gothic Castle Style, but he fully rebuilt the inside, adding a magnificent staircase and stained glass dome. Although no longer used as a capital building, it is today open for tours.

William Freret died in New Orleans on the December 5, 1911 at the age of 78. He was buried in the Army of the Tennessee Tumulus in Metairie Cemetery, final resting place for a number of veterans of the army. Freret, by virtue of being a Shiloh and the Kentucky Invasion, was entitled to a place. Buried near him was Beauregard, the man who prompted Freret to come north and begin his unusual military career.

I would like to thank Katrina Horning for helping me with research for this piece.

Interesting article.

I wonder if he is related to Jules Freret, 2nd Company Washington Artillery?: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7840717/jules-freret

Thank you for the information. I am going to look into that.