A.P. Hill’s Death Wish?: The Problem with Using Quotes

Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill rode to his death during the immediate aftermath of the April 2, 1865 breakthrough at Petersburg. Hill sought to meet Major General Henry Heth at the division commander’s Pickrell house headquarters. Instead he encountered Pennsylvania soldiers John Mauk and Daniel Wolford just 800 yards from his objective. Some have speculated that the reckless nature of his final journey meant that Hill may have been going out in a blaze of glory—a suicide by Yankee. As proof, they quote Hill saying less than a week before his death that he did not want to survive a Confederate defeat. Historians, however, should be wary of interpreting anything more from that supposed statement.

Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill rode to his death during the immediate aftermath of the April 2, 1865 breakthrough at Petersburg. Hill sought to meet Major General Henry Heth at the division commander’s Pickrell house headquarters. Instead he encountered Pennsylvania soldiers John Mauk and Daniel Wolford just 800 yards from his objective. Some have speculated that the reckless nature of his final journey meant that Hill may have been going out in a blaze of glory—a suicide by Yankee. As proof, they quote Hill saying less than a week before his death that he did not want to survive a Confederate defeat. Historians, however, should be wary of interpreting anything more from that supposed statement.

A skilled brigade and division commander, Hill failed to duplicate that success at the corps level. He had feuded with Stonewall Jackson and could not live up to the high expectations as his somewhat successor (Jackson’s command was divided between Hill and Richard S. Ewell). Hill suffered from illness frequently during the last year of the war. His Third Corps played an important role in the Petersburg campaign, but the general was a relative non-factor.

On March 20, 1865 Hill took a brief leave of absence to restore his health. He stayed at his extended family home in nearby Chesterfield County. Both the Thomas and Henry Hill families are shown to be living or seeking refuge on the property. Uncle Henry worked as a Confederate paymaster in Richmond and the general accompanied him into the city on March 29th. George Powell Hill, one of Thomas’s sons, also worked in the paymaster department. He afterward wrote that A.P. Hill did not wish to live if the city fell. Here is the relevant excerpt from G. Powell Hill’s statement:

During this visit to my father’s home he accompanied Colonel Hill to Richmond, and while seated in our office talking with several prominent citizens who had called to pay their respects, the subject of the evacuation of the city was touched upon, which seemed to annoy the General, and he remarked that he did not wish to survive the fall of Richmond.

Thus it should be noted that the quote is just a secondhand source and not an actual written or documented statement. However, if an author writes that Hill said he did not “wish to survive the fall of Richmond” it implies that it is a direct quote, which can therefore be construed as proof that Hill was indeed trying to get himself killed on April 2nd. The author might not even have such an agenda. It is awkward to work the G. Powell Hill postwar account detail into a narrative flow. Footnotes allow for clarification but there is no guarantee the reader will consult them. It is too easy to simply see “did not wish to survive the fall of Richmond” and accept it as fact.

The entire account from George Powell Hill should also be treated as what it is. Though an incredibly useful resource for learning about the first of three burials for A.P. Hill, Powell’s statement is not a window into the general’s mind. The article was written in 1891 when Hill’s body was being dug up for the second time to be reinterred as the centerpiece for new development north of Richmond. Recalling events after a quarter century is challenging enough, determining someone else’s personal opinion is nearly impossible.

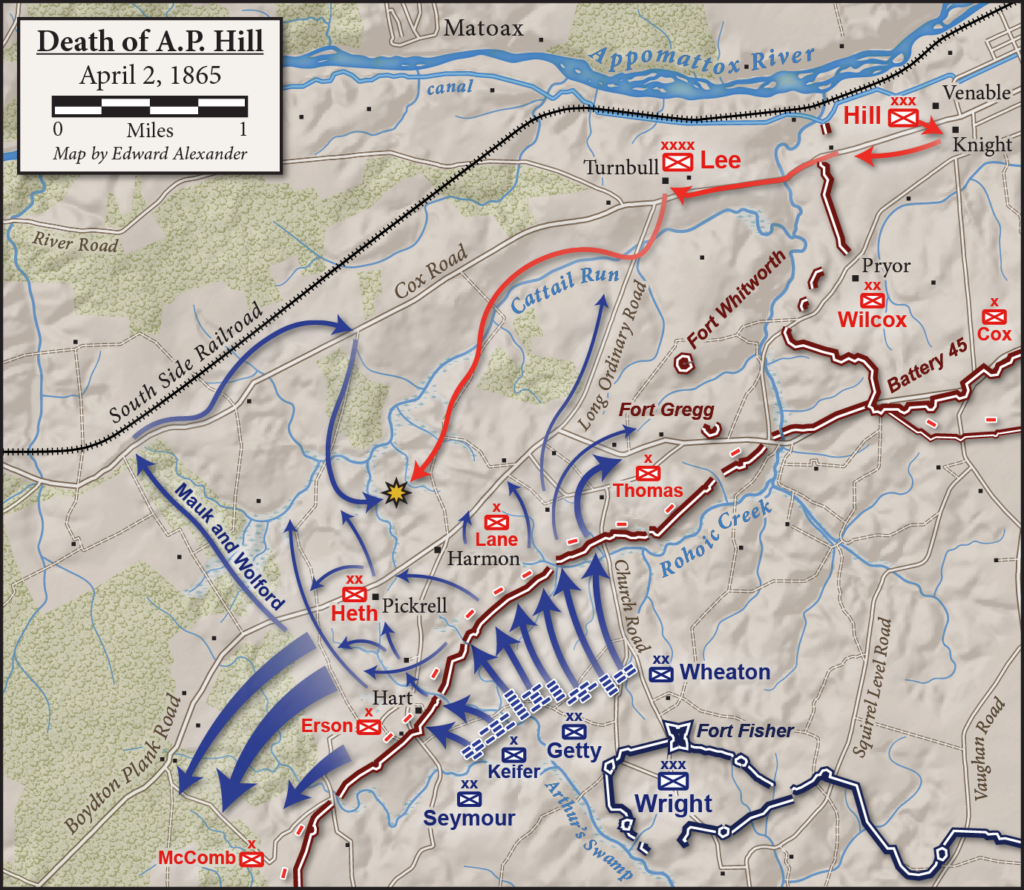

Regardless of his mindset at the end of the campaign, General Hill returned to command on April 1st. He spent the last day of his life inspecting his lines from Hatcher’s Run to Battery 45, and settled in for a restless night at the Venable house on Petersburg’s outskirts, where his pregnant wife and two young daughters slept. Kept awake by Union artillery fire, Hill saddled up at about 3 a.m. to ride to Lee’s headquarters a mile and a half to the west at Edge Hill. Along the way he learned that his own lines were under attack. He discussed strategy with Lee and James Longstreet until sometime after 5 a.m. when Lieutenant Colonel Charles Scott Venable brought news that Federal infantry had broken through along the Third Corps position.

Hill immediately wanted to meet with Heth, the division commander responsible for the Confederate fortifications from the Hart house south to Hatcher’s Run. He was accompanied by Venable and couriers George Washington Tucker, William Henry Jenkins, and George Percy Hawes during various stages of his ride from army toward division headquarters. A small component of infantry briefly attached themselves as escorts but Hill shed his companions along the way until only Tucker remained for the final showdown with the Pennsylvania pair.

Corporal Mauk’s bullet struck Hill but Private Wolford missed Tucker and the courier hastily escaped to inform Lee of Hill’s death. In 1883 Tucker wrote his recollections for the Philadelphia Weekly Times “Annals of the War” series. The account is highly reliable as a guide to the progress of Hill’s last ride and in describing the encounter with the Pennsylvanians. Mauk also wrote several accounts of his shot that killed Hill. The Union and Confederate versions proved remarkably consistent.

Tucker’s article portrayed the general as distant and impatient. He claims to have ridden along Cattail Run at Hill’s side but the general hardly spoke to him.

Proceeding still further and General Hill making no further remark, I became so impressed with the great risk he was running that I made bold to say: “Please excuse me, General, but where are you going?” He answered: “Sergeant, I must go to the right as quickly as possible.” Then, pointing south-west, he said: “We will go up this side of the branch to the woods, which will cover us until reaching the field in rear of General Heth’s quarters, I hope to find the road clear at General Heth’s.”

… When going through the woods, the only words between General Hill and myself, except relating to the route, were by himself. He called my attention and said: “Sergeant should anything happen to me you must go back to General Lee and report it.”

Tucker claimed that he spurred his horse ahead of Hill as they crossed an open field in order to reach a swampy forest opposite Heth’s headquarters on the Boydton Plank Road. When two-thirds of the way across the field they spotted Mauk and Wolford in the treeline running perpendicular to the plank road and additional Union soldiers further into the woods.

I looked around to General Hill. He said: “We must taken them,” at the same time, drawing, for the first time that day, his Colt’s navy pistol. I said: “Stay there, I’ll take them.” By this time we were within twenty yards of the two behind the tree and getting closer every moment. I shouted: “If you fire, you’ll be swept to hell! Our men are here – surrender!” When General Hill was at my side calling “surrender,” now within ten yards of the men covering us with their muskets (the upper one the General, the lower one myself,) the lower soldier let the stock of his gun down from his shoulder, but recovered quickly as his comrade spoke to him (I only saw his lips move) and both fired. Throwing out my right hand (he was on that side) toward the General, I caught the bridle of his horse, and, wheeling to the left, turned in the saddle and saw my General on the ground, with his limbs extended, motionless.

Tucker’s narrative is wonderfully quotable and all modern versions rightfully utilize his dialogue, even though the exact exchange had likely been altered after eighteen years. Removing those quotes and all others in similar situations would certainly make history rather boring, but, if they are to remain, readers should be wise to not accept them as gospel.

Furthermore, Tucker’s account showed that it was Hill who acted recklessly during the ride. Colonel William Henry Palmer, Hill’s chief of staff, believed that Tucker misrepresented which of the pair was aggressive that morning. Palmer remained at Third Corps headquarters until he received news from Edge Hill that the Confederate lines were under attack. He traveled to Major General Cadmus Wilcox’s division headquarters inside Petersburg’s Dimmock Line (the main set of entrenchments surrounding the city) and then rode toward army headquarters by way of the Boydton Plank Road and Long Ordinary Road.

Palmer claimed that he encountered Tucker at that road junction as the courier frantically returned from Hill’s death site. Supposedly Tucker informed the chief of staff about what happened as the two rode together to Lee’s headquarters. In a November 8, 1902 letter to Captain Murray Forbes Taylor, a Third Corps aide-de-camp, Palmer stated that Tucker had changed his story in between that fateful April morning and the 1883 publication. Palmer believed Tucker did so to shift blame from himself, writing:

Gen’l Hill lost his life doing a chivalrous thing. When Tucker rushed forward, & ordered the two skirmishers behind the tree, to surrender, Gen’l Hill for the moment remained behind on a slight elevation. He saw that they were going to fire on Tucker, & were not going to surrender. It was no longer a Lieut General and his courier. He spurred his horse to Tucker’s assistance. It was man to man. Tucker told me that he had no idea that Gen’l Hill was near until he heard the snort of the Gen’ls horse, just as the two skirmishers fired.

Palmer believed that he would have been a better escort to Hill that morning and regretted that the general had ordered him to remain at corps headquarters for further instructions.

If the General had have allowed me to accompany him [I] have always felt assured that I could have impressed him with the importance of avoiding scattering parties of the enemy & the keeping well to the right near the Cox Road… I say this because I had influence with him about such matters, & feel assured that on two occasions during my service I saved him from wounds by cautioning him & taking precautions for him.

The chief of staff believed that Hill acted as he normally would in battle and that Tucker’s careless desire to capture Mauk and Wolford led to the general’s death. Of course that cannot be proved either, but Palmer’s objection to Tucker’s account demonstrates that there are plenty of rational reasons to explain the bizarre encounter between Hill and the Pennsylvanians.

During the lectures and tours I have led about Hill’s death I have found the “suicide by Yankee” scenario is nevertheless popular. Those who promote that idea use the same reasoning, based in part on Hill’s illness and a speculated but ungrounded desire by the general to restore his legacy, but primarily reliant on the quotes from George Powell Hill and George Tucker. Eliminating those quotes dries up the story so I’m not advocating their exclusion entirely. I freely used them in my chapter on Hill’s death in Dawn of Victory. With disclaimer, I will continue to do so. But what worked for narrative is unreliable for analysis.

Many people are drawn to the Civil War because of its rich personalities, but we should be cautious in trying too hard to think that we can therefore fully understand them. The quotes that make Hill’s last ride compelling portray him as acting too reckless but they were written several decades after the war. Despite their appearance in quotation marks, they were not the general’s actual dialogue. Remove that hearsay evidence from the notion that Hill willingly rode to his death and that theory falls apart.

Sources:

George W. Tucker, “Death of General A.P. Hill,” Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume 11 (Richmond, VA: Published by the Society, 1883).

G. Powell Hill, “First Burial of General Hill’s Remains,” Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume 19 (Richmond, VA: Published by the Society, 1891).

William H. Palmer to Murray F. Taylor, November 8, 1902, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park.

Bud Robertson spells Mauk as Mauck with a C in his book “General A. P. Hill – the Story of a Confederate Warrior”. I am curious where you got the Mauk spelling from. You may have found a better source.

I’ve seen the Mauck spelling in a few postwar newspaper articles but his service and census records, mentions in the official reports, headstone, and everything else says Mauk. Not sure why Bud spelled it the other way. A few short obituaries, like the one in the August 26, 1898 Everett Press, even give us his middle name–Watson.

Thanks for the clarification on the spelling. I have enjoyed your articles on the loss of A. P. Hill, you have answered a lot of my questions. I can’t imagine that Hill would let somebody kill him on purpose.

I’ve read it many times about Hill and Tucker trying to get the the two Union troops to surrender. I’ve always wondered: WHY? If getting to Heth was his priority so that decisions could be made as to how to contain the Union attacks and/or breakthroughs, why bother with such a task? Did they think they could get some useful information out of them? Did they HAVE to neutralize them so they could proceed? They were in the open and the Union troops in the wood line. Seems to me that they could have spurred their horses out of danger, given the difficulty of hitting moving targets with muskets. Regardless, it always seemed rather wasteful to do such a thing, given the situation.

Exactly what i was thinking. It cant be true. His only objective was to get the Heth and discuss and strategize about the overall prob of the breakthrough. Taking prisoners ends that idea immediately. Unless they planned on interrogating them to find out more but I’d say just seeing them there answers most of those questions.