Herman Haupt: Reopening The Rail Lines To Gettysburg

“I am now at Hanover Station. A bridge is broken between this place and Littlestown. I will proceed at once to repair it, and commence to send off wounded; then return and take the Gettysburg Railroad and commence repairing it. It will be well to make a good hospital at York, with which place I expect in two days to be in communication by rail. Until then, temporary arrangements can be made for the wounded. I learn that the wire is intact for nine miles toward Gettysburg. I will have it repaired and communicate any information that I can obtain.”[i]

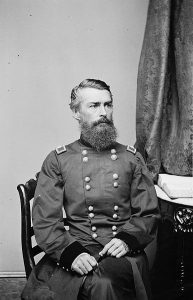

General Halleck received that message from Herman Haupt on July 4, 1863, and felt reassured that railroad lines to Gettysburg would be restored soon. Haupt – one of the best men for the job – had won the trust of Lincoln, the cabinet, and high ranking officers. If anyone could get the trains to the war zone in Southern Pennsylvania, this civil engineer would do it. Interestingly, Haupt had lived in Gettysburg for about ten years and knew the area well.

Herman Haupt, born March 26, 1817, grew up in Pennsylvania and attended West Point. Graduating in the Class of 1835, Haupt served in the military for only three months, resigning to start a career in railroad engineering. The following year he arrived in the Gettysburg area, searching for a route for the iron horses over South Mountain to Hagerstown. Haupt spent the next ten years in Gettysburg, teaching at Pennsylvania College, writing an engineering book, building a house on Seminary Ridge, and starting a family. He left Gettysburg to accept the powerful and strategic role of General Superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad. By 1861, Haupt had built six major railroad lines and had been recognized as a leader in the field of civil engineering.

As it became clear the divisive national conflict would last longer than ninety days and Union armies grew exponentially, the system of supplying the military network was in shambles. Quartermasters knew they needed supplies but did not always have the knowledge to coordinate large scale efforts to keep the wagon trains moving and the railroad cars rolling. In 1862, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton reached out to Herman Haupt, asking him to take control of army transportation. Haupt seemed reluctant and laid down a list of requirements, including stipulations that he would avoid all work on the Sundays for religious reasons and he would not accept a military commission or draw pay, allowing him to carry on personal business without reference to the military. Surprisingly, Stanton agreed – probably because he desperately needed someone to bring order to the situations. Haupt accepted the rank of brigadier general, but – as agreed upon – did not take a commission or pay.

Under Haupt’s direction, the railroads and transportation systems improved, a remarkable feature considering the Confederate’s continual attempts to disrupt the lines. When tracks were destroyed, Haupt rushed crews to repair the damages. He even gained President Lincoln’s approve and commendation for the construction of Potomac Run Bridge in May 1862. “That man Haupt has built a bridge…about 400 feet long and nearly 100 feet high, over which loaded trains are running every hour, and, upon my word, gentlemen, there is nothing in it but beanpoles and cornstalks.”[ii] Though slightly exaggerated, the bridge had been constructed by common soldiers who had no previous engineering skills. Haupt drafted the design, gave the orders, and watched two million feet of raw lumber felled from the nearby woods transform over the course of nine days into the bridge he envisioned.

Haupt quickly became a vital player in the Civil War, evidenced by his brief departure. Irritated by General John Pope who decided to put quartermasters in charge of all supply transportation, the civil engineer packed his bags and headed home to Massachusetts. Several days later, the War Department was proverbially on its knees begging him to come back. The telegram read: “Come back immediately; cannot get along without you; not a wheel moving on any of the roads.”[iii] Haupt’s skill and authority had been appreciated and recognized.

Thus, the man who studied the maps and heard the reports of rail damage during the Confederate Invasion of Pennsylvania in 1863 was well qualified, trusted by officials, and in a position to solve the problems. In Washington City on June 28, Haupt learned his West Point classmate George Meade now commanded the Army of the Potomac and decided to do a little scouting as he checked on the state of rail lines in southern Pennsylvania. As the armies clashed at Gettysburg, Haupt arrived in Westminister which was twenty miles from the fighting and the closest point of undamaged railroad tracks. No trains arrived however, and military officers rushed about, shouting the supplies they needed, waiting for Haupt to work a miracle.

Haupt sent them away for a few moments. “I asked them to give me a few minutes to think, and to escape the crowd I crept into a covered wagon and hid myself.”[iv] When he climbed out of the wagon, Haupt had a plan. The trains might not get to Gettysburg in time to transport battle supplies, but it was vital to get the lines open to bring the wounded out and get medical supplies and rations to the survivors.

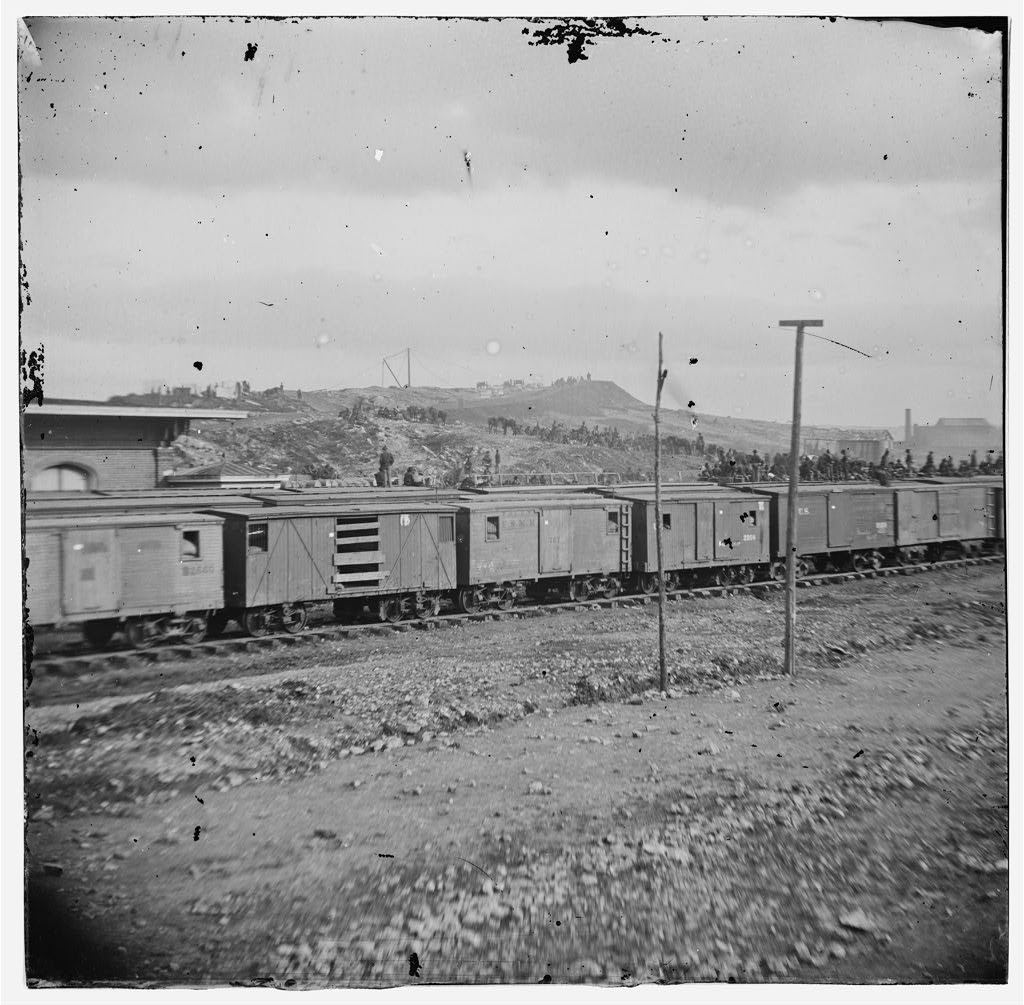

The local civilian superintendent of the railway begged Haupt to take over, willing to step away from the nightmare. The un-commissioned general took charge, bringing in his own railroad crew of four hundred men and a supply train with railroad ties, track, and tools. Over twenty miles of single track and several bridges had to be built or repaired before a welcome whistle could pierce the air at Gettysburg. He posted guards to keep Southern sympathizers from messing with the repaired tracks and issued orders to get supply trains moving to Westminister. Thirty trains a day arrived at that point, ensuring the Army of the Potomac had rations arriving which could be moved by wagon toward Gettysburg.

By 11p.m. on July 4, 1863 – hours after Haupt sent the original message to Halleck – he followed up, reporting that the bridge near Oxford would be in working order the next morning. In a race to save lives, Haupt was just seven miles from Gettysburg, having already repaired about eighteen miles of track. The following morning Haupt arrived in Gettysburg (by buggy) to evaluate the situation. Ironically, it was Sunday when he arrived in the town where he had lived for a decade, a day he had bargained not to work. However, necessity and extreme situation at Gettysburg prompted Haupt to revise his principles just for that day. He worked on Sunday, bringing the trains closer and closer to the horrible scenes.

The entire Gettysburg area was one vast field hospital with wounded lying in every structure, in the fields, in the woods, and directly in the rain. By this time, Jonathan Letterman’s battlefield medical system called for injured men to be moved from the field hospitals to larger hospital facilities; the railroads were key to this process, and Haupt had worked toward this goal for days.

By July 7, 1863, just three days after the fighting ended, Haupt’s crews had brought the railroad tracks to the outskirts of Gettysburg. The bridge over Rock Creek which ran east of town still needed repair (the Confederates had burned it on June 26th), but Haupt, confident the military quartermasters in Gettysburg could oversee that final project, headed back to Washington to report on the situation.

Two days later Haupt returned to Gettysburg to make sure everything ran smoothly and found the still-unrepaired bridge, stacks of desperately needed supplies pushed off the trains in the fields, and 4,000 wounded men waiting for transportation by rail car. Livid, Haupt seized control of the rail line from the civilian operators, oversaw the repairs at Rock Creek Bridge, and set up a time table for the trains.

Two days later Haupt returned to Gettysburg to make sure everything ran smoothly and found the still-unrepaired bridge, stacks of desperately needed supplies pushed off the trains in the fields, and 4,000 wounded men waiting for transportation by rail car. Livid, Haupt seized control of the rail line from the civilian operators, oversaw the repairs at Rock Creek Bridge, and set up a time table for the trains.

Gettysburg only had a single track in and out of town, and Gettysburg was the “end of the line.” Haupt and the other military officers who oversaw the operations after he left set up a train schedule to effectively bring in the cars, off load the supplies, and place the wounded in the cars.

Haupt stayed with the Union Army only two months after his work at Gettysburg. Frustrated by the pressure to accept commission, pay, and orders, he went back to Massachusetts, leaving the military to figure out its own transportation problems. Haupt believed he had been a victim of politics, but perhaps his effectiveness and power had frightened some in the government. Though not his intention to cause a problem, Haupt showed he could solve logistical problems without the army and without bureaucracy when he brought the trains to Gettysburg. With his military partnership over, Haupt launched into the next part of his career, publishing reams of engineering and technical papers and eventually becoming manager of the Northern Pacific Railroad, overseeing the completion of the rail lines to the west coast in 1881. Throughout his brilliant and recognized career, one of Haupt’s greatest triumphs remained quiet in the pages of history.

If Herman Haupt had not started working on the railroad tracks before the fighting even ended in Pennsylvania, the loss of life could have been worse than it was. His efforts to bring food, medical supplies, and an effective evacuation method to the battle area literally saved lives. The railroad cars rocked, swayed, and jerked over the miles of track Haupt and his men had laid or repaired, and thousands of wounded men on their journey from the horror fields and overcrowded medical facilities at Gettysburg did not know who to thank for their comparatively swift evacuation. Similarly, in the rows and rows of books about Gettysburg, few pages are devoted to the work of this remarkably tenacious civil engineer.

Sources:

[i] Gerard A. Patterson, Debris of Battle: The Wounded of Gettysburg. (1997), page 37.

[ii] Ibid, page 34.

[iii] Ibid, page 34.

[iv] Ibid, page 35.

Haupt is one of the best of the “B” list players in the war–great stuff!

I think I know what you meant but I doubt that anybody who studies this area regards Haupt – or Meigs or Letterman – as “B List” players.

Excellent work revealing this logistical master

An unsung hero who saved many lives.Thank you

What a guy… and what a story! Thanks. There should be a monument to him, at Gettysburg or in Washington.

Looking, looking, looking for a photo or sketch of that bridge before it was burned.

postmaster@sandhillcity.com