On Watching Gone with the Wind in 2018

Patricia Dawn Chick (born Acker) was my mother. Her favorite movie was Gone with the Wind. It might seem odd since she was from Indiana, but her roots went back to the Dossett family of Kentucky. They were ripped apart by the Civil War. They fought on both sides, veterans of Fort Donelson, Vicksburg, Tullahoma, Brice Crossroads, Tueplo, Franklin, Nashville, and Selma. Some chased John Hunt Morgan during his Kentucky raids. One rode with Nathan Bedford Forrest. Another was on the staff of William Loring before he deserted and ran off with the horse he was given. Their fates were varied, from death and desertion, to chronic illness, dishonorable discharge, and fighting to the bitter end. My mother was no doubt drawn more to the romance and sweep of the film, but the family lore was clear that the Dossetts had some tense family meeting in the decades after.

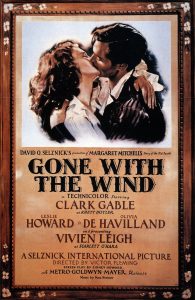

After Mom died in 2014, I avoided watching Gone with the Wind. Yet, a poster of it hangs on my wall. I had it framed as a Christmas present, a gift she never saw. As time went on I wanted to see it again, but then statues started to come down and a theater in Memphis decided to stop showing it. I worried if it would it now feel tired, dated, silly, and racist? It flies in the face of the current orthodoxy about the Civil War. It is considered a Lost Cause relic, and even a centrist historian like Jon Meacham thinks there is no value in this old interpretation.

The Prytania Theater, the oldest in New Orleans, did a showing on August 25, 2018. I half feared there might be some protest although there has been a bit of protest exhaustion after the statues came down. I wondered if anyone would be there. When I saw Chinatown and Escape From New York, neither film had a lot of people in attendance. Would I only see old white people? However, the audience was large, mostly white but not exclusively, and generational mixture was surprising. There were even teenagers who were shocked it did not end with Rhett Butler and Scarlett O’Hara together. All in all, surprising for 10am on a Sunday, when most are at church, hungover, or eating brunch.

On the big screen it is a captivating film. The music has a sweep and grandeur and the images are powerful. It is one of the only films where the paintings do not seem like dated special effects but masterworks deserving a place in the Met. The acting is uneven, but the film had to be carried by Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh and neither disappoints.

Watching the film, I was deeply moved by the first half. Scarlett calls out for her mother while Atlanta is shelled. Eventually, she sees her dead mother. More than that, there are qualities to Gone with the Wind that few Civil War movies capture. For one, it has the odd structure of showing life before, during, and after the war. Only The Deer Hunter comes to mind as using the same formula, and both films do not quite feel like war movies even if they are. Gone with the Wind is compartmentalized into four parts: eve of war, war itself, reconstruction, and a failed marriage. I like parts of each, but the reconstruction section is the weakest. The war section is the most powerful and unusual in that it deals with civilians and not soldiers.

In Gone with the Wind, war is hell. It is a very unheroic film, in that way a product of its time, an era artistically dominated by the popularity of the novel and film All Quiet on the Western Front. By contrast, Glory and Gettysburg both generally adhere to a heroic conception of combat. The tragedy in each is that of defeat: Battery Wagner does not fall and George Pickett’s division does not break the line. I believe these are the parts that make each film among the best. By the same token, Lincoln is a heroic film, although it is expressly political. It too ends with a kind of defeat, as Lincoln fails to implore the South to give up in 1865. He asks “Shall we stop this bleeding?” only for the film to cut to Richmond burning and Lincoln riding among the dead, images that invoke Scarlett’s flight from Atlanta.

There is a mood of demise in Gone with the Wind that connects it more closely with one of the least talked about Civil War movies, but I believe among the best: Pharaoh’s Army. That is a story of moral ambiguity and bitterness, and in that sense the two are kin. Pharaoh’s Army though is about poor people and is a darker movie. Gone with the Wind is more about a civilization transformed, while Scarlett is transformed from a selfish flirt to a hard-nosed entrepreneur. Where Gone with the Wind always impressed me was in having a hero who is flawed, even despicable. Scarlett is not really that emblematic of the moonlight and magnolias view of Dixie. Indeed, there are precious few magnolias and the only time we see moonlight is to show that Tara still stands, but in a desolated land.

The film makes no bones that the Confederacy was a fool’s enterprise, encapsulated when Rhett Butler mentions the South has no factories but a lot of arrogance. Ashley Wilkes, the symbol of the old South, is depicted as weak, vacillating, and lost. Scarlett realizes only at the end she was a fool to keep any attachment to Ashley and therefore to a world that is gone. The film is in part a conflict between practicality and romance. Scarlett is practical, her attachment to the old South is an attachment to a past she rejected the moment she said she would never go hungry again, launching a personal war to save her home.

Death and destruction are not treated lightly in Gone with the Wind. To the bloodier minded the war was worth it since it ended slavery and saved the union. Yet, republics are not supposed to solve such things with death and destruction. When we cheer the North’s victory, and the falling of statues to common soldiers, we cheer the defeat of our fellow countrymen. Lincoln’s plea, which I quoted earlier, is itself a reply to Stephens asking a question often ignored in recent Just Cause scholarship: “How have you held your Union together? Through democracy? How many hundreds of thousands have died during your administration? Your union, sir, is bonded in cannon fire and death.” I do not come to say the South was right, only that the pain of defeat is treated too lightly as of late.

Gone with the Wind, better than any other film, masterfully depicts the shock of destruction, physical and emotional. It resonated in 1939 with a people still reeling from the Great Depression while across both oceans the fascists were on the march and a destruction greater than Atlanta in 1864 loomed. World War II even drew in the film’s actors. Leslie Howard died on a passenger plane shot down by the Luftwaffe while Clark Gable was nearly killed flying in a B-17 over Germany.

I recently read that Gone with the Wind was popular in Japan. Not when it came out. By that time anti-western feelings were on the rise and films were being banned. Yet, a few copies were found when Singapore fell and the people who saw it marveled at the technical skill and lavish production, some even doubting if Japan could win against an opponent capable of such feats. That technical skill produced the very weapons that would level Japan. In 1952, when the film got a formal release, it was a big hit. Japanese audiences admired Scarlett and no doubt saw themselves in her. They were moved by the scenes of Atlanta ablaze, drawing parallels to the destruction of their cities.

How one feels about war itself determines in part how you feel about Gone with the Wind. I became enamored with the movie during the lead up to the Iraq War. I watched Gone with the Wind and Tora! Tora! Tora! several times before the bombs fell on Baghdad. The big brash talk of war in the parlor of Twelve Oaks matched the same talk I heard in the cafeteria at the University of New Orleans. The Iraqis can’t fight. One American can whip ten terrorists! It was all brash stupidity. To be fair, few people are openly pro-war, but we do look for justifications to assuage our conscious. The idea that the South was “forced” to fire on Fort Sumter was the lie spread after defeat. So too is the myth that the war was inevitable and necessary and good. It is at heart a way to feel okay about killing each other 150 years ago.

Gone with the Wind resonated with me as a teenager because it was about the war. I loved the unusual story of a failed romance between two people of questionable moral character. Today, it resonates because my mother is dead and I know what that is like for Scarlett. Being from New Orleans, I also know what it is like to see your city destroyed and to rebuild in the wake of destruction, knowing that the world before the storm cannot be reforged. I at least though, unlike Gone with the Wind, do not rommantize pre-Katrnia New Orleans too much. It was wilder, cheaper, but also even less safe (if you can believe that) and very stagnant.

Recently, the time capsule in the pedestal of the P.G.T. Beauregard statue was opened. A reporter asked why there was a Confederate memorabilia stuffed in it 49 years after the war was over. It is a question, I dare say, steeped in ignorance and judgment. Some are appalled that anyone could feel sad the South lost or that they clinged to the memory of the war. If they do they must be racist. Yet, the answer lies in part in the graves across America and the shared regional experience of defeat. A woman I dated recounted that her grandfather worked on civil rights in the 1960s, but was proud of his ancestors’ Confederate heritage. What she saw as dumb and silly, I saw as a wonderful complexity that gives me hope. Hamilton Basso, himself a civil rights advocate, also wrote a sympathetic biography of P.G.T. Beauregard, who was himself an advocate for civil rights. One need not adhere to the current Manichean sensibility in our culture. I find the racism in Gone with the Wind a liability, as well as its class dynamics. The film is very harsh towards “poor white trash” which aptly describes my ancestors trying to survive in Tennessee poverty. I also recognize there is more to the movie than that.

I am glad Gone with the Wind still exists. It is not an accurate depiction of history, but nor is any movie. It is another interpretation, at times ridiculous, but we impoverish ourselves if we explain away its past popularity as some marker of backwardness. The scenes of death and destruction, the very waste that Rhett Butler curses in the wake of Gettysburg, cannot be dismissed. The sweeping camera in the Atlanta rail yard is one of the most stark depictions of war ever put to film.The war devastated the South. It left a bitterness that resonates even today with every condescending remark about how we should “get over it,” often coming from people obsessed with other past calamities. My ancestors on my father’s side survived the war, lived as Tennessee farmers for generations after, while my Irish ancestors scrapped by in New Orleans. The story of enduring defeat and deprivation is real, and talking about it need not eclipse or weaken the parallel story of civil rights. The two are not mutually exclusive and form the fabric of the South and of America.

I felt the sweep of war watching Atlanta fall in a dark movie theater. My heart raced and I was moved nearly to tears as Scarlett moved about a blighted land looking for her home and her mother and a world that never was. That world was never real, we only saw it from her point of view. The reality was the world she had to make for herself. She survived in that world, and although she made money, she never thrived. She lost two husbands, friends,family, love, and respect. In that way, Gone with the Wind is honest about what happened after the war. In the South, we survived but we never healed. We still cannot heal, and the pessimist in me says we are not likely to, so long as empathy is reserved only for chosen groups and not for others. Yet, when I cleaned my mother’s apartment in 2014 I found a Gone with the Wind music box that plays the main tune. I wind it up on occasion. Mostly it sits on my Civil War bookshelf, where I sometimes look at it when times are hard.

I felt the sweep of war watching Atlanta fall in a dark movie theater. My heart raced and I was moved nearly to tears as Scarlett moved about a blighted land looking for her home and her mother and a world that never was. That world was never real, we only saw it from her point of view. The reality was the world she had to make for herself. She survived in that world, and although she made money, she never thrived. She lost two husbands, friends,family, love, and respect. In that way, Gone with the Wind is honest about what happened after the war. In the South, we survived but we never healed. We still cannot heal, and the pessimist in me says we are not likely to, so long as empathy is reserved only for chosen groups and not for others. Yet, when I cleaned my mother’s apartment in 2014 I found a Gone with the Wind music box that plays the main tune. I wind it up on occasion. Mostly it sits on my Civil War bookshelf, where I sometimes look at it when times are hard.

It is no wonder the Japanese enjoyed the film; they have the code of Bushido and formal etiquette

Great point David.

It always fascinates me which movies are hits elsewhere. For instance, Liar Liar was popular in Iran because culturally they are interested in the value of telling the truth. It goes all the way back to the Persian Empire.

There can be no doubt of the grandeur of the film as a movie. As a statement about the events of the period, it is as some medieval churchmen characterized women: a temple built over a sewer. The representation of the Reconstruction is outright perjury; a massive tissue of bald-faced lies. It should be seen for what it is: a masterpiece of cinema. As history, it ranks up there with Sleeping Beauty.

I think the first half holds up well as history as far as movies go. Few American films are as honest about the horrors of war for the civilian population and I respect it for avoiding a heroic interpretation.

The Reconstruction part is the weakest, but not wholly without merit. The struggle to keep Tara illustrates the financial woes of Reconstruction. Reconstruction is also thankfully the shortest part, since the last hour is a grand marriage drama.

In terms of films which are utter fantasy, I would say The Patriot and Braveheart are worse offenders. Yet, I would not suggest Gone with the Wind is anywhere near something like Tora! Tora! Tora!

This is the best piece on the Civil War/Lost Cause/”memory” I’ve read in quite some time.

Nicely done and thoughtful article. Thank you

GWTW is a movie–not an accurate depiction of a historic event. I still get goosebumps when I think of that scene of Atlanta’s field hospital, and I feel terrible for the images of returning Confederate soldiers, but those goosebumps and empathy are no different from the feelings I get from a speech John Buford never really gave or from the piles of Union corpses in theatrical sand dunes being lapped by–no doubt–computer generated waves. All are well worth watching repeatedly, imho.

I agree Meg. I love Buford’s speech. One of the best in film history.

In Glory it is the scene where they charge and when they breech the walls. All is chaos and yelling, and you are impressed with their courage and the music is going but then out come the cannons. The next scene for the Rebel flag goes up is superb and sad.

I saw Glory when I was 8. I reeled back when the officer gets his head blown off at Antietam. I still do.

In terms of watching GWTW this time I actually forgot about the enormity of the wounded in the rail yard. Upon seeing it I had a sudden shock I will never forget.

What a thorough and thoughtful review. I must admit, I never quite made it through the entire move, only watching parts here and there. I’ll have to watch the whole thing and try to understand the feeling that you have for this movie. Thanks for your view on this!!

A very beautiful,deep and meaningful article about so much more than GWTW…thank you !!

Thank you for writing this. Many people from other regions of this country may never understand why southerners feel the way they do. It took the south over 100 years to recover economically from the destruction, total war, the north waged on the south and the civilian population. There was no Marshall plan to help the south recover, she was left to fend for herself. Prior to the war, those visiting the U.S. noted that there were 2 distinct cultures in America, divided by the Mason Dixon line. In many ways it’s still there.

From a purely cinematic viewpoint, many of the propaganda films produced by the Nazi regime of Hitler were excellent, even ground breaking. The same can be said of the horribly racist Birth of a Nation. Gone with the Wind, in my view, is in the same category.

The movie’s supposed cinematic excellence cannot hide its many historical flaws. It’s depiction of life in the Old South is a laughable fantasy. The majority of white Southerners at the time lived in illiterate poverty. To black slaves, Southern plantations resembled Nazi concentration camps. Only a relative handful of oligarchs lived like the inhabitants of Tara. And, of course, racism permeates most of the film.

For my money, Gone With the Wind is way too long and in many spots downright boring. It reminds me of a bad daytime soap opera.

Obviously you know very little of history when making comparisons.

Feel free to fill us in. And while you’re at it, explain how many of the African American actors in the film were invited to the premiere in Atlanta.

You make a good point about Griffiths’ salute to the Klan. Even more than GWTW, that movie broke all sorts of new cinematic ground. It’s unfortunate that the script was something white supremacists loved.

Something that troubles me about Birth of A Nation is comparing it to Griffith’s Intolerance, The Rose of Kentucky, and some of his short films. There is an incoherence to the man that is baffling.

I don’t think Gone with the Wind is the same league as Nazi films, communist films, or Birth of a Nation. The later truly is as awful as described. GWTW, whatever its limitations on race, is not a KKK propaganda movie and Mammy is probably the sharpest person in the film. Birth of a Nation glorifies martial violence. GWTW does not. I also do not think it romanticizes the Old South as much as advertised.

At times though, it is like a bad soap opera, but Rhett Butler is always there to remind you how ludicrous Ashley Wilkes really is.

Birth of a Nation had a plot that partly pivoted around racism and enforcing White supremacy. It would not be the same story without those elements.

Gone With the Wind, on the other hand, could of treated its black characters with dignity. Those characters could of been given a voice, that part of the story could of been changed to one which was sympathetic, and I think it would of actually been a better story. The plot could of stayed EXACTLY the same.

GWTW, yes, has racism in it and a very Southern point of view who’s time has come and gone. But the main characters and the story actually don’t revolve around putting down nonwhites. The actual message is about Feminism and the lack of choice women had at the time. I see so many reviewers getting upset about African American rights in the film, and forget Scarlett was as helpless legally as a 5 year old, like almost all women at that time, and had to rebuild her family finances in a culture very hostile to working women.

My grandparents on my mom’s side were from large Southern families who owned slaves before the civil war, and lost everything after. They were steeped in bigotry from the moment they were born. Brainwashed and threatened to never, ever believe anything else. Sadly, otherwise, they were wonderful grandparents, well liked and respected in the community as well.

Bigotry is a horrible disease, and I agree it needs to go away, but, understand, if you were white, and went against the racist rules of the time, your life would be destroyed. People put each other under huge amounts of pressure to spread and maintain the lie. It took brave people to leave their families and reach out to a group outside of their own.

I saw my own grandfather take out a bible and strike my cousin’s name from it when they found out she had dated a black man. The rest of my family rallied around my cousin, and made my grandparents realize times were changing, but it was not a good time for any of us. Growth takes pain, and many people still want to avoid it.

From the article:

“Yet, republics are not supposed to solve such things with death and destruction. When we cheer the North’s victory, and the falling of statues to common soldiers, we cheer the defeat of our fellow countrymen.”

I think it should be remembered that it was the leaders of the rebellion that chose to initiate war rather than using a political or legal process to validate their secession claims.

And when we cheer the victory, it is the victory of the Nation, not the victory of the North.

From my article:

“The idea that the South was “forced” to fire on Fort Sumter was the lie spread after defeat.”

So as you can see, I make it clear who choose the war.

Also it was a victory it was for the North. If it had been a true national victory there would have been a Marshall Plan for the South and no curtailments of civil rights legislation. Neither the Gilded Age political ethos nor even the later Progressive one offered good solutions to these problems.

A any rate, I will always despair at the thought of my family literally shooting at each other. It is one of many things that gives the war its particular tragic sensibility.

In my opinion, labeling the victory as for the North rather than a victory for the Nation, ignores Unionists in the South, southerners who fought for the Union, and Blacks in the South. Many southerners aligned themselves with the Nation, or at least were not aligned with the rebellion.

It’s interesting that the Japanese liked the movie. The Japanese have had more difficulties in figuring out how the second world war is treated in cultural memory, as compared to the Germans. Perhaps there are similarities between the Japanese and the Lost Cause adherents.

That is a fair point about Southern Unionists of any variety. That said, those groups did not have a great postwar experience. Arguably, outside of a few New South boosters, few people did. So the scars are still there and the victory has a ring that is tragic for some and incomplete for others.

I think the degree to which the Germans have “figured out” their defeat in World War II is overstated; the lines of debate are still there and it is debate with no real end, since it will shift as circumstances shift.

Few peoples or countries ever “take blame.” Part of the emerging comparisons between the Confederacy and the Nazis (more a symptom of limited historical imagination than anything useful) is the idea that the South did not take responsibility. The more I read about other wars, the more I see that idea is really just a recent phenomena in the west (Mongolians love their Genghis Khan statues), and itself incomplete among those countries.

Japan took an interesting path. Admit nothing, but also put in place rules and mores to make sure you never do it again. I do like that the horror of war and defeat is a consistent motif in their post 1945 art.

I’m reluctant to credit Japan with too much. They have pretty much just ignored the extensive Nazi-like activities they undertook in China and, to a lesser extent, in Korea. Part of the problem with that sort of “non-memory” is evident in the fact that we still “debate” the cause of secession even though its advocates were quite clear about the cause and had no reluctance in saying so. My ancestor fought on the Union side and I have no reluctance in admitting that he appears to have shared some of the extant racial views of many at the time (including Lincoln) and that those views objectively are wrong. Same goes for the so-called “Indian Wars”. A nation has no greatness if it cannot admit to shortcomings in its past. Obfuscation, concealment, and distortion should have no role in that process.

The money quote: “we impoverish ourselves if we explain away its past popularity as some marker of backwardness.” Indeed. The bane of modernity with so many things.

Nothing like those good old days.

Richard:

I have nothing against looking back at the good old days. After all, like all ECW fans, I’m a Civil War fanatic. But one of the great things about history is that it allows us to put things in perspective. We can analyze the good and the bad in ways that people living at the time could not do accurately.

For instance, throughout the 19th century (and much of the early 20th century) a majority of whites – both in the South and North – believed blacks to be intellectually inferior. We now know – with the perspective of history – that this thinking was terribly wrong-headed.

Not so long ago, women were thought to belong in the kitchen, not in the work place. Women were not perceptive enough to vote. Native Americans should forget their heritage and become “Americanized.” Gay life styles were thought to be a matter of choice rather than being born that way. Gone with the Wind was an Oscar-winning hit at the box office when it was first released, rather than being damned for its racism.

You get my drift.

We have to balance out the parts of the past that hold less value for us and those that mean something. GWTW has its limitations, but those have been discussed at length. I wanted to discuss why it still has power and popularity.

I hold to a tragic and cyclical view of history instead of the progressive one. In that sense, what a historical artifact means changes over time. Certainly GWTW meant more to me after Katrina, monument removals, and the personal experience of losing family as well as going through failed relationships.

Perhaps because of our era’s current call out culture, and the current social justice trend in art, I am much more interested in why people like something than discussing its particular social value.

Then there’s this: I am currently reading a book on prisons during the Civil War. I would not have known about leasing teams of prisoners for labor is not for GWTW.

Meg, please let me know if it is all inclusive, I may like to read it. Here in DE, at Fort DE, confederate POWs were sometimes chained outside of the fort when the tide was out and left to drown when it came back in. War brings out the worst in humans.

The book is Penitentiaries, Punishments, and Military Prisons: Familiar Responses to an Extraordinary Crisis during the American Civil War, by Angela M. Zombeck. I am reviewing it for a Civil War publication. It is very interesting and relies on some interesting primary sources.

What is truly amazing about ‘GWTW’ is that it is still being shown in these days of revisionist history and efforts to erase significant aspects of our history. Maybe all should make a recording of it the next time it plays on a TV channel, or go out and buy a DVD of it, because it just might become a collector’s item if certain folks ever have their way. I look at ‘GWTW’ as a period piece, but not one of the 1860s. I look it at it more as a reflection of late 30s America. It does hold up via its cinematic scope. As far as racial portrayals, the ones shown to be of true positive character are Mammy and Big Sam, and of course Melanie. It is the magic of movies that we can actually pull for someone as despicable as Charlotte, just like we pull for gangsters in movies and TV shows today. Regardless, I always make it a point to watch it when it comes on TCM.

Thank you for this article. Movies are limited by time and what the public will pay to watch. In the 1930’s, Civil War movies were seen as box-office poison.

When I watch the movie (and I am a fan of it) I see a study of the effect of the Civil War Era on Southern women. It is a story about how strong women (Scarlett, Belle Watling, Mammy) survive by developing the skills they need .

Your last paragraph hits on its persistent popularity among women. Most of its fans that I know are professional women, often but not always of Southern background. My love of the film has actually served as a bonding agent with some people, and of course it was among the first old films my Mom watched that I was interested in.