Mistake or Cover Up? Seven Pines, May 31, 1862

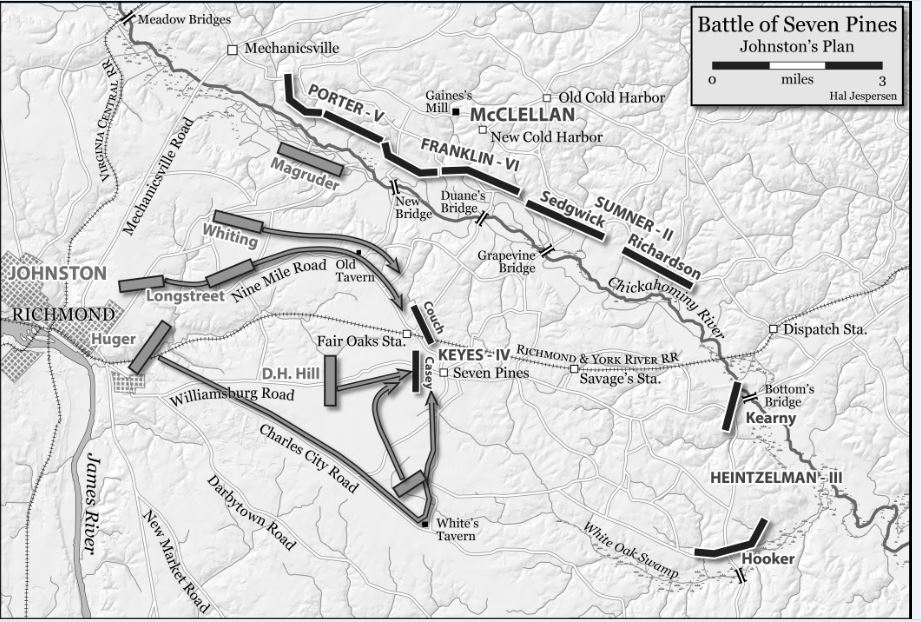

In late May 1862 George McClellan’s massive army was at the outskirts of Richmond, trying to move a few miles closer to the city so it could employ its massive siege guns. Confederate commander Joseph E. Johnston was desperately searching for an opportunity to strike and drive McClellan back. At the end of the month he found his opportunity. The rain-swollen Chickahominy River divided the Federal army. Three corps were positioned north of it, and south of the river Erasmus Keyes’ IV Cops was dangerously exposed at a place called Seven Pines. According to Johnston’s second-in-command, General Gustavus W. Smith, the Confederate commander planned an attack for May 31. D. H. Hill would move west and attack Keyes along the Williamsburg road. James Longstreet would move down the Nine Mile road and strike the Federal right flank. Benjamin Huger would march down the Charles City road and strike the Federal left. Keyes could be destroyed. It was a bold plan, but it held promise.

As so often happens in a battle, plans are soon ruined by faulty execution. Instead of taking the Nile Mile road, Longstreet moved his troops to the Williamsburg road, in support of D.H. Hill. In doing that he crossed a swollen stream called Gillies’ Creek… this took some time. Unfortunately, Huger needed to cross at the same place, and had to wait for Longstreet’s division. Huger was seriously delayed, and he also lacked clear instructions. As ordered, Hill attacked, the Federals were driven back a short distance, but by the end of the next day things were pretty much as they had been before the battle began, less some 11,000 unfortunate casualties (one of which was Johnston himself).

This is where things get interesting. In his Battles & Leaders article, “Manassas to Seven Pines,” Johnston stated, “Longstreet … was instructed verbally to form D. H. Hill’s division as first in line, and his own as second, across the road at right angles.” However, in his own B & L article (“Two Days of battle at Seven Pines”), Smith stated that Johnston wanted Longstreet to move down the Nine Mile road.

In his report in the Official Records, Johnston said “Had Major-General Huger’s division been in position and ready for action when those of Smith, Longstreet and Hill moved, I am satisfied that Keyes’ corps would have been destroyed.” Longstreet echoed this in a June 7 letter to Johnson, in which he said, “I can’t help but think that a display of his forces on the left flank of the enemy by General Huger would have completed the affair.” He continued: “The failure of the complete success on Saturday I attribute to the slow movements of General Huger’s command.” An interesting comment considering that it was his division that held Huger’s command up!

Smith was having none of this. To him, Huger was, in today’s terms, being “thrown under the bus.” In his book The Battle of Seven Pines, he repeated his assertions as to Johnston’s plan, and further stated that Huger’s instructions were not clear (Johnston’s orders of May 30 & 31). He also cited a letter from D.H. Hill of May 18, 1865, in which Hill said, “I cannot understand Longstreet’s motive in coming over to the Williamsburg road, nor can I understand Johnston’s motives in shielding him.” On June 13, 1885, Hill wrote to Smith about Longstreet’s June 7, 1862 letter to Johnston saying, “I can’t understand how he (Longstreet) had the brass to write such a letter.”

The most damning evidence of all was mentioned in Smith’s B & L article, on which he quoted a June 28 letter to him from Johnston. The latter mentioned “two subjects which I never intended to make generally known, and which I have mentioned to no one but yourself…. I refer to the misunderstanding between Longstreet and myself in regard to the direction of his division… as it seems that both of these matters concern Longstreet and myself alone, I have no hesitation in asking your to strike them out of your report.”

Did Longstreet’s mistake result in the unraveling of Johnston’s plan? Were the casualties pointless? Was Huger unfairly made the scapegoat? If you’re interested, be a detective. Look into it yourself and decide!

I think that Longstreet protesteth too much. However, what always amazes me is that Keyes was sticking out like a sore thumb in the first place. McClellan was always whining about being being in imminent peril of being swamped by overwhelming hordes of rebels. So why did he even create such an inviting target as Keyes? Why was Porter and the AOP main supply depot later left on the north bank, even after the extended delay of McDowell’s advance? The only obvious conclusions are one of two: either McClellan really did not believe he was outnumbered; or worse, he thought the Confederate command mirrored his own timidity and would not attack. After Seven Pines, and Jackson’s boldness-even recklessness- in the Valley, McClellan’s misreading of the Confederate will was negligent in the extreme.

One of the theories out there is that McClellan kept two guys he didn’t like – Keyes and Heintzelman (add the latter’s two division commanders) – away from where he thought the fighting would take place. Aside from that poor prognostication, the alignment made no sense by having Keyes’ weaker division (Casey) at the front and the Third Corps well away from the front.

Dangling Keyes out there kinda worked in luring the Confederates out of their defenses to fight in the open but I highly doubt that was McClellan’s plan. Evaluate what his strategy did accomplish through the Peninsula and Seven Days, however, and you can’t help but think that U.S. Grant would have loved to provoke the rash, haphazard attacks that Johnston and Lee launched on McClellan. McClellan could not see his plan through to victory in 62 and the Confederates would not oblige Grant the same way in 64.

Would be curious to know if the June 28 letter exists. If so, it would be fairly convincing evidence that Johnston and Longstreet are guilty of covering up the botched orders and using Huger as a scapegoat. I think we have yet to see a definitive study of the Battle of Seven Pines.

Very true. It often is just seen for the opportunity it gave Lee to rise to command. By the way, Smith is actually buried in New London Connecticut. But keep it quiet, a lynch mob may head to his tombstone!

Steve Newton’s book is still the best. It’s fairly thin and the maps are primitive, but the analysis is solid.

I don’t know if anyone can explain the “seniority” debate at the crossing in a way which makes Longstreet appear to be reasonable. The result was that Longstreet crossed first and delayed Huger getting across. That’s entirely aside from the fact that Johnston chose to issue verbal orders to Longstreet and imprecise written orders to the others for a complicated set of movements.

What? Say WHAT? Commanders in the Civil War assigning blame while not taking any on their own? Say it ain’t so. Longstreet has always been an enigma. At times he appears to be brilliant, at others he seems to be quite ‘ordinary’. He often comes across as flat out insubordinate. No one can argue his fighting ability, but given how many times his leadership did contribute to Confederate successes, it’s fair to ask if his actions might have PREVENTED a real chance for the Confederates to prevail.