Railroads: “I took to it quite naturally.” Beauregard as Railroad Executive

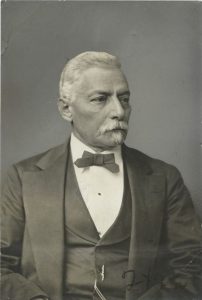

In 1865 P.G.T. Beauregard entered upon his next act of life widowed, defeated, and without much money. Beauregard returned to New Orleans, which had escaped the destruction that laid waste other cities. It was still a premiere commercial center and offered opportunities. Beauregard was not a plantation owner and although he came from wealth, he did not live a lavish lifestyle. Before the war he was exclusively a renter. He was a superb engineer in a society that was mechanizing.

Beauregard’s first employment following the war was in October 1865 as chief engineer and general superintendent of the New Orleans, Jackson, and Great Northern Railroad Railroad. In short order Beauregard got the railroad going again, but the company’s finances were in ruins due to the war and unpaid bond interests. In 1866 he was promoted to president of the railroad. Beauregard went to Europe in 1866 on business and met with Napoléon III to discuss naval technology. While in Europe, Romania, offered Beauregard command of their army, and a large cash reward, but he declined. Instead, he convinced European creditors that the Jackson Railroad had a future. The company was saved.

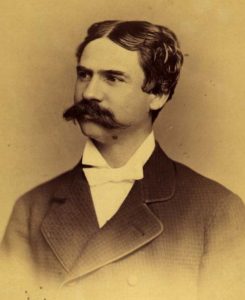

Beauregard’s success on the Jackson Railroad brought him to the attention of the New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad Company, which connected the Crescent City to the town of Carrollton just to the west. It was a German immigrant town and local resort spot. During the Civil War the Union used it as a major camp, but its bars were popular with Union officers. Grant famously visited the town after Vicksburg fell, got drunk, and fell off his horse.[i]

The railroad was failing and in 1866 Beauregard overhauled the line, updating its locomotives and equipment. However, his business partners, Thomas May and A. C. Graham, were financially negligent. The result was a scandal. Beauregard it was agreed was little at fault, but there was guilt by association and Beauregard feared his reputation would not recover. Regardless, he stuck with the railroad and made it profitable in the years ahead.

To Lee he wrote “I took to it [railroads] quite naturally.”[1] However, after years of success there was trouble ahead. The Jackson Railroad’s stock was mostly owned by the state of Louisiana. In 1870 Henry Clay Warmoth, the Republican governor, decided to sell the stock. Warmoth was the archetype of the corrupt Gilded Age politician. W.E.B. Du Bois dubbed him an “unmoral buccaneer, shrewd, likable, and efficient.”[2] Warmoth decided to sell the railroad to Henry C. McComb of Delaware, who in turn loaned Warmoth $30,000. [3] McComb was the founder of the Southern Railroad Association, which sought to create a regional monopoly. Warmoth, for his part, believed the path to Republican power in Louisiana was through prosperity, which meant the railroads. When questioned about his aggressive support for railroad schemes he boasted, “It is just the policy pursued in Illinois, in Indiana, and in Iowa. It is just the policy pursued in Missouri, where they have six or seven thousand miles of railroad, and are not a dollar in debt.”[4]

Beauregard refused to turn over the stock to McComb and a bitter fight ensued. The company split between those supporting Beauregard and McComb. At one time McComb and his backers entered Beauregard’s office and demanded a new board election. Beauregard declared “This is an illegal election. I order you out.”[5] Some men offered to throw them out. Beauregard refused to go that far but he did have the men arrested.

On June 17, 1870 the court sided with McComb, who personally came to remove Beauregard. The old general accepted his fate and pleaded that his employees not be ousted. McComb, perhaps to add insult, told Beauregard if he had not fought him he would have been retained. At any rate, Beauregard was right to say “We took it [Jackson Railroad] when it was in ruin, and turn it over to you now in pretty good condition.”[6] In the corrupt world of nineteenth century American politics, Beauregard was a novice. McComb paid off Warmoth while Beauregard failed to marshal political support in his fight. The railroad though later proved to be a milestone around McComb’s neck. The railroad fell into debt of $21,391,000 by 1874 and McComb could not pay his workers. By that time, state aid was nonexistent, in no small part because corruption weakened the allure of railroad subsidies.

In the end, Beauregard’s greatest achievement after the war was his railroad work in Carrollton. Despite efforts by Republicans to investigate the company, it became successful. In 1869 he demonstrated a cable car and was issued U.S. Patent 97,343. He implemented a system of cable-powered street railway cars that were the genesis for the iconic streetcars of New Orleans. Yet, in 1876 Beauregard was removed by stockholders who wished to take direct management of the company. In the game of institutional politics, he was again defeated.

Beauregard was a talented and successful general and engineer. Yet, he lacked a knack for politics. During the war it led to a bitter feud with Jefferson Davis. After the war it meant that despite being a scrupulous and successful railroad executive, he ended up being forcibly removed from both of the railroads he saved from ruin.

Sources:

[i] Rose, Grant Under Fire, page 254.

[1] Williams, Napoleon in Gray, page 278.

[2] Du Bois, The Black Proletariat in Mississippi and Louisiana in Black Reconstruction

[3] Summers, Railroads, Reconstruction, and the Gospel of Prosperity, page 103.

[4] Ibid., page 142.

[5] New Orleans Picayune April 26 1870

[6] New Orleans Picayune June 18 1870

Yes, politics wasn’t his strongest suit although he was oft engage in politics in some way or other. Maybe a bit too earnest of a man for the horror that is American politics.

Beauregard is in part to blame for his shelving by Jefferson during the war (another political failing on Beauregard’s part), although I think Jefferson is more to blame in not realizing he had to use what men he had… and Beauregard was one of his better men. Maybe if Beauregard and Jefferson had some interaction to form a relationship, as Lee and Jefferson had, things might have gone different.

Beauregard lived an interesting life.

Davis and Beauregard were very friendly before Bull Run, and he functioned in the early months as a kind of unofficial advisor. The trouble was in part political, as Davis’ enemies rallied around Beauregard, who for his part was not conciliatory in the political battles. If I fault Davis it is in not giving Beauregard his due for his victories in 1863-1864. Without a doubt, it should have been Beauregard instead of Johnston or Hood in charge of the Army of Tennessee, as Lee advised Davis on both occasions.

Beauregard ran for mayor of New Orleans in 1858 and lost. He advocated for equal rights but was booed. All of his forays into politics were disasters.

Yeah, I understand that. The anti-Davis politicos in the Confederate Congress championed Beauregard and Beauregard seriously ruffled Davis after Manassas with his impolitic letters to Davis. I guess my point is to say Beauregard wasn’t physically around Davis for that long. There relationship was one of distance for the most part. Yes, Davis would visit him in camp and Beauregard transited through Richmond, but they mostly were sending letters to one another. Lee, on the other hand, was in Richmond working side by side with Davis which proved important for the two of him. No doubt Lee had more sense in dealing with Davis.

Grant’s horse accident, coincidentally, occurred along the tracks of the New Orleans & Carrollton Rail Road and was apparently caused by the horse’s taking fright at the appearance of a locomotive.