Christmas in the Hospitals: Bringing Cheer to a Dreary Holidays

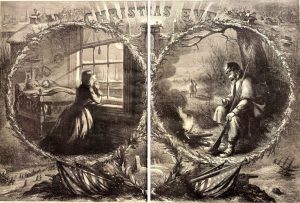

It is never fun to spend the holidays in the hospital and it was no different during the Civil War. Soldiers in pain from battle wounds or suffering from diseases or infections, sometimes exasperated by wartime shortages, made the holiday difficult to enjoy. Yet, while celebrating the holidays during the Civil War was always a challenge, soldiers, surgeons, and civilians did what they could to make the holiday a pleasant one for as many as they could.

Christmas in 1861 was particularly a challenge since it was the first winter of the war. In the spring and summer many thought the war would be over by Christmas; instead many soldiers suffered outside in winter camps for the first time in their lives in unsanitary living conditions that sparked diseases that spread throughout the camps. Diseases such as meningitis, measles, yellow fever, typhoid, and pneumonia raged through the camps costing thousands of lives at the beginning of the war. For example, at Camp Jones in Bristow, Virginia, hundreds of soldiers from Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia died from diseases and other ailments caused by poor sanitation, though only soldiers from the 10th Alabama have been found.

For the soldiers in the hospitals, everyone did what they could to try to bring some joy and hope to the soldiers for the holidays. In 1862 and 1863, President Abraham Lincoln visited soldiers at various hospitals around Washington D.C. One year he even took his son, Tad, with him. Tad was so moved by his visit with the soldiers that he sent gifts to the soldiers including books and clothing. Local women, Soldiers’ Aid Societies, and Relief Associations banded together to try and provide for the soldiers in the hospitals. While collecting hospital supplies throughout the rest of the year, during the Christmas holiday they helped to collect and prepare decorations for the hospitals including flags and greenery as well as a feast for the local hospitals, making sure that the soldiers had not only enough food to eat, but quality food including turkey, duck, vegetables, pies, and sweets.

One letter in the Anne Arundel County Trust for Preservation’s archives describes what Christmas was like for Northern soldiers towards the end of the wary. Benjamin Barrows of the 31st Maine Infantry was a patient at the U.S. Army Hospital in Annapolis in 1864, wrote a letter on Christmas Day that tells of the celebrations provided to soldiers:

Christmas has passed off very pleasantly here. We have celebrated by eating a better dinner than common. Our dinner consisted of roast turkey, ham, potatoes, pickles, plum pudding and apple pie, and each of us (got) a mug of lager bier, thanks to our surgeon, Mynheer Dutchman. This is what those on full diet had. … Others had extras suited to their condition.

… Out in town last evening there was considerable shooting in honor of this day, something like our celebrations of the Fourth of July … There have been numerous sleigh rides. I fancy I can almost see the teams and hear the merry jingling of the bells as they go past…

However, Christmas wasn’t always a happy time of year for many including Sgt. Barrows. He found himself also in charge of the dead house at the hospital, responsible for cataloguing and burying those who did not make it. He continues his letter writing “I am in charge of the dead house. This has been a fatal Christmas to many. I think 20 have been carried into it today. One hundred thirty have been buried this week”. By the end of the war, over 650,000 lives would be lost due to infections or disease and this caused many to have to experience Christmas at home without fathers, sons or brothers. As newspapers covered the war, they would remind readers of the somber times around Christmas, such as the Weekly Standard from Raleigh, North Carolina that printed:

Whilst we write, the warm blood from the heart of many a strong man and bright eyed boy no doubt reddens the soil. The whole nation is a vast house of mourning. Christmas, once so merry and joyous, now finds the widow and her little ones clustered together in grief. Carnage, blood, fiendish malignity, devilish hate, ail the horrors of hell, seem to rise uppermost and turn the land into a vast slaughter-pen…

The holidays were a bleak time of those impacted by Civil War and everyone was trying to make the best of it in the hospitals to provide a little bit of relief from the grim realities of war. Though no matter how hard people tried, the effects of the war would be felt for many holidays after, as family members struggled to carry on the holiday cheer with those unable to return home.

As this Christmas approaches let’s all of us offer prayers and whatever support we can to those Americans that serve in outposts, known and unknown, throughout the world. And their families as well.

Amen to that suggestion.

Thanks, Paige, for the interesting account of Civil War Christmas, an excellent reminder to count our blessings this December 25.

Your account of the woes due to cold, wet weather and disease in Confederate Camp Bristow at Christmastime, 1861, reminded me of a letter to his parents in New Hampshire my then 22-year-old and very homesick great grandfather wrote on Dec. 25, of that year. This probably was his first holiday season away from hometown. He described the stormy days before Christmas in the Army of the Potomac’s Washington, D.C., Camp of Instruction. He refers to the suffering of sick and wounded in hospital tents towards the end of the excerpt below.

“I suppose the proper way to commence my record today would be with a merry Christmas to all of you… Our rain storm cleared off in a snow squall and came out in a gale of wind and a cold snap… I seldom have heard the wind blow harder, and it froze up tight. You may imagine that a tent would not be the most comfortable place in which to pass the night. I confidently expected every moment that the tent would leave us. We could keep no fire for our stovepipe chimney blew down, and I have not passed such a disagreeable night on the ground. Those who had fireplaces were even worse off, for the wind drove the fire all over the inside of the tents and came near causing a general conflagration. We have all drawn another blanket and now are comfortable. In the gale two hospital tents blew down leaving the sick unprotected. I can hardly help referring to this worst phase of winter camp vis [a vis] treatment of the sick, and their number. In our Reg. the 2nd, of 700 men 150 are on the sick list. Two men died night before last…”