Mr. Lincoln: Though The Eyes of Gustav Koerner

Two hundred and ten years ago. Ten score and ten years ago. That’s when Abraham Lincoln was born in a tiny, chilly cabin near Hodgenville, Kentucky. February 12, 1809. At that time, none could have imagined what he would accomplish his fifty-six years of life or the enduring legacy and image of his life and leadership.

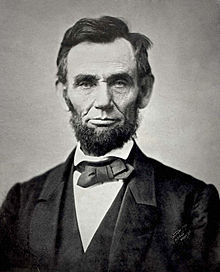

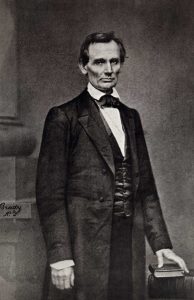

Hundreds of volumes, academic papers, and student essays have tried to definitely answer the reason for Lincoln’s enduring greatness. Scholars spend years searching for the keys to Lincoln’s success. Through the decades, pop culture, art, and even propaganda have used Lincoln successfully to uphold an array of causes. His photographs, portraits, and other images are literally everywhere – probably even in your pocket or purse right now. Marble and granite sculptures of Lincoln stare at the distant horizons of freedom at Mount Rushmore, keep a watchful eye on the Capitol, and seem to gaze at visitors in museum galleries.

Abraham Lincoln had many roles in his relatively short lifetime. Farmboy, country lawyer, friend, husband, father, representative, speaker, president, commander-in-chief, mourner, emancipator – just to remember a few. When I finally started to draw my own informed conclusions about Lincoln, the words and perspective of one of my ancestors helped to present an honest, unvarnished image of this remarkable man.

On March 4, 1861, Gustav Koerner wrote to “dearest Sophie” to inform his wife of the history-making moment he had witnessed.

“Lincoln is President. In the presences of at least ten thousand people he took the oath and read with a firm voice his inaugural. I stood close to his chair; next to me stood Douglas. On the other side of Lincoln stood Buchanan and Governor Chase of Ohio; opposite to him, Chief Justice Taney. At the close of his speech he was cheered by thousands. The weather was fine and the greatest order prevailed.”

Lincoln’s journey to the inaugural moment into the executive office and Koerner’s journey to America paralleled and intersected, creating a unique supportive relationship that literally changed the world.

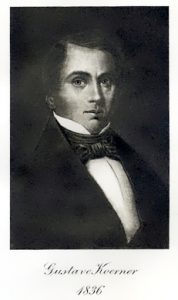

Gustav Koerner – also born in 1809 – grew up in Frankfurt, Germany. By 1833, this well-educated young man fled his homeland after getting mixed up in a student uprising and getting a case number for investigation of his “revolutionary ideas.” Arriving in the United States, Koerner planned to live in Missouri which had a growing population of German immigrants; however, slavery’s horrors tormented this freedom lover, and he eventually settled in Illinois, began studying and practicing American law, and became a U.S. citizen in 1838. Koerner’s active role in law and government introduced him to Abraham Lincoln, the country lawyer and rising state politician. In the 1840’s, Koerner served in the Illinois House of Representatives, becoming the first German American elected to representation in Illinois. He spent three years on the Illinois Supreme Court and in the early 1850’s held office as lieutenant governor of his homestate.

His previous experiences and voice in the immigrant community gave Koerner the expertise to influence history. With the 1860 Election ahead, Koerner knew Abraham Lincoln needed support and also offered an opportunity for freedom’s advancement. Working with other influential German-Americans, Koerner and others orchestrated a platform and voting scene in the “Wigwam” that secured the Republican nomination for Lincoln. They also rallied the German-American press and immigrant citizens to vote for the Railsplitter.

Years of connection in state politics and trials had forged a relationship between Koerner and Lincoln. The presidential election and impending Civil War brought them closer. As Lincoln encountered an array of office seekers and ambitious cabinet members, the two men from Illinois had important discussions about the state of the Union and what to do about Southern secession. Later, Koerner remembered that through these conversations he “was brought nearer to Lincoln than ever before, [though] I cannot say that there was any warm friendship between us” because Lincoln did not seem “really capable of what might be called warm-hearted friendship.” Supported and backed by Gustav Koerner – who also represented many freedom and Union-loving German-Americans – Lincoln took office.

As the cares of politics and war plagued Lincoln and his administration, he seemed less connected to the friends who had secured his position. Koerner remained supportive and even used his influence to try to smooth ethnic difficulties between the president and the immigrant communities or immigrant generals. A rift occurred between Koerner and Lincoln over diplomatic service, but by 1864, Koerner was back, listening to the troubles over the impending election and plotting how to use immigrant influence to keep Lincoln in the White House. At the president’s request, Koerner visited without a formal purpose, and the two spent time talking about their earlier days in Illinois.

Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in 1865 shocked and grieved Koerner and his family. They were honored to learn that Gustav Koerner had been asked to be one of pallbearers for the funeral in Springfield. The man who had helped elect the president and who had spent hours advising, listening, and discussing local, state, and national politics with Lincoln tragically escorted the president to his final resting place.

Koerner had worked for the ideal of freedom in Germany and the United States, in Illinois and Washington, with country lawyers and presidents. His fight for humanity did not end with Lincoln’s death, nor did his connection with Lincoln become the defining hallmark of Koerner’s life, the way it did for some of Lincoln’s other acquaintances and friends.

However, because of his connection to Lincoln, Gustav Koerner had seen that man’s character, heard his stories, felt Lincoln’s struggle with friendships, and observed his greatness and faults. His conclusion about Abraham Lincoln echoed honest respect.

“To analyze such a highly complex character as that of Mr. Lincoln, and to give a correct portraiture of it is a task which many have undertaken, but in which [few], if any, have fully succeeded. I knew him well enough to have been able to detect certain weaknesses and defects in his character. The great and good, however, largely perponderated… Mr. Seward had said of Mr. Lincoln that he was the best man he ever knew. I should rather say he was the justest man I ever knew.”

Today, Lincoln is hero-worshiped. Truth often mixes with stories and legends. Sometimes, though, the amount of information and conflicting views can obscure the subject – the man – even more. That’s often how I feel about Lincoln. He has been studied extensively and yet I think perhaps he is still elusive.

As I think about Lincoln, the Civil War, and that embattled president’s legacy, I’m grateful for the words of my great-great-great-great-grandfather – a man who knew Lincoln in the courts, who campaigned fiercely for Lincoln, and who listened and advised in the dark, lonely days of 1861. When I feel conflicted by the hero-worship juxtaposed to the primary sources, puzzled by the dirty jokes compared to the great speeches, and awed by the tenacity and accomplishments for freedom and union by the sixteenth president, I find myself remembering the words of Gustav Koerner: “He was the justest man I ever knew.”

Happy Birthday, Mr. Lincoln.

Source:

Allendorf, Donald. Your Friend, As Ever, A. Lincoln: How the Unlikely Friendship of Gustav Koerner and Abraham Lincoln Changed America, 2014.

When I think of Lincoln, I think of someone who tore the Constitution asunder, someone who destroyed the government our founding fathers gave us and replaced it with one that they feared. I think also of the roughly 800,000 thousands of Americans that lost their lives, of the utter destruction of those seeking independence with the southland, still being the poorest region of the country. That’s what those that know the whole history think of.

If we’re looking for “the whole history”, fill us in on the habeas corpus commissioners in the CSA and their duties; the restrictions placed on private property by Davis’s government; which government first enacted a sweeping confiscation act; and how many civilians were held in Confederate military prisons and why. And then we’ll get to the big topics – such as who committed acts of illegal rebellion which led to the deaths of possibly 850,000 and who fought that rebellion in order to keep millions of human beings as chattels to be bought, sold, and occasionally beaten.

It is so nice to be able to reach back through time and connect in such a meaningful way with our ancestors.

Though it is nothing like your connection, I have a great-uncle who was one of the early Texas Rangers. He wrote a wonderful autobiography at the end of a very eventful life. It was published by the University of Texas at Austin Press. I like the fact that the veracity of his recollections have been “vetted” by every serious scholar who writes about the early Rangers. Otherwise, I am not sure I would have believed all his stories.