Huzzah! …And The War Came to the Yankees, Part 1

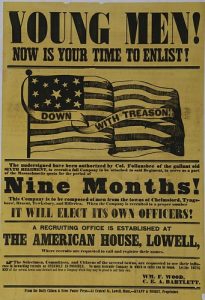

Despite the messages, threats, and concerns, brave little Fort Sumter held on. The waters were cold, the food was minimal, and information even more scarce than the food. Major Robert Anderson, garrison commander, had moved his group of Army regulars to Sumter from Fort Moultrie on December 26, 1860. Now it was April, Abraham Lincoln lived in the Executive Mansion, and seven states had officially seceded from the Union. A flurry of personal intercessions occurred–boats came rowing up to the fort and back to Charleston, but no one was satisfied. Early in the morning of April 12, 1861, Confederate guns around Charleston Harbor opened fire on Fort Sumter. At 2:30 pm on April 13th, Major Anderson surrendered the fort and evacuated his troops the next day. On April 15, 1861, the start of the American Civil War, the President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, called for a 75,000-man militia to serve for three months following the bombardment and surrender of Fort Sumter.

It was about time! Unless one held an elected position in Washington or had access to the corridors of power in some other way, people felt helpless when it came to all the talk about differences in the country. These issues–nullification, extending slavery to the territories, fugitive property returns, and all the other things that had been causing bloodshed in Congress and elsewhere since the 1840s–must be resolved. If it was war, well, some things were worse than war.

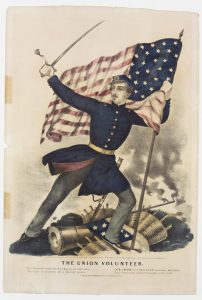

Northern cities and towns buzzed with excitement. Young men (and women), only two generations removed from that of the Founders, were anxiously excited to be given a chance to prove that they could defend the Union as well as anyone. Were there uniforms? No. Did anyone know how to march or move as a coordinated group in battle? No–at least not yet. But surely everyone could learn, and it would be such a lark–oh my! Things like quotas and numbers of men to make up a company, squad, or regiment were not important either. The Union, however? Now THAT was important.

Some men were already members of town militias, and some just wanted to sign up. Indiana offered twice as many volunteers as requested. Massachusetts men were the first to arrive in Washington on April 19, only four days after Lincoln’s announcement. Elmer Ellsworth staggered out of his sickbed at Willard’s Hotel (he had caught the measles from Willie and Tad Lincoln), went to the Executive Mansion, and left with a letter of recommendation from Abraham Lincoln to Horace Greeley. Within a week Ellsworth had personally recruited over a thousand New York firefighters. Within two weeks the 11th New York Fire Zouaves were bunking down in the capital building itself. Kansas and Oregon sent men to join other companies since both states had been excluded from Lincoln’s original call.

In May, President Lincoln gave a second call for an additional 42,000 men. He issued a further appeal for United States Volunteers to serve three years, with regiments to be organized by the state governments. He increased the regular US army by 22,714 men. In July 1861, the U.S. Congress sanctioned Lincoln’s acts and authorized 500,000 additional volunteers.

There are many letters left to us by these “Boys of ’61.” They run the gamut from delight and pride to complaining about their new lives as soldiers. They were afraid, lonely, disgusted, and could not wait until there was a battle in which to prove themselves. Pennsylvanian Henry D. Wharton wrote (May 21, 1861), to “Wilvert” from Camp Wayne about the revolt held by some men from his company. The food served in camp was not “fit for a South Sea Cannibal,” and four hundred men paraded their protests:

The men formed in procession, with a man carrying, in advance, a long piece of board for a flag-staff–a piece of pork and beef made the flag, and a biscuit, on top, for a spear …the Colonel was pelted with sea biscuit. The Commissary’s horse was completely covered with the biscuit–a string of biscuit around his (the horse’s) neck, (pity it hadn’t been a rope around the Commissary’s) biscuit for a saddle girth–biscuit to the tail, and biscuit on the foot of each leg …and if you ever saw fun, it was here.[1]

Not all the boys were “boys.” Grown men with wives and children volunteered in 1861. Major Sullivan Ballou wrote to Sarah, his wife:

… I cannot describe to you my feelings on this calm summer night, when two thousand men are sleeping around me, many of them enjoying the last, perhaps, before that of death–and I, suspicious that Death is creeping behind me with his fatal dart, am communing with God, my country, and thee.[2]

Fathers wrote to their young children, trying to comfort them and reminding them to “be good.” New Yorker Luther Bruen wrote to his little ones Selia, Frank, and Robert:

Papa was very sorry to go away and leave you and dear mother and he hopes you will all be good children so as not to give her any trouble. You must all try to keep out of mischief & do whatever mother tells you to do. Papa will be very sorry when he comes home if mother can not tell him that you have all been kind to each other and obedient to her.[3]

Poet Walt Whitman added his thoughts about the young men on their way to war. 1861 was a year of hope for the Union. A look at the images, especially those that have been colorized, show us young faces. America’s head had not yet been bowed down with the weight of grief like it was in 1863 and beyond. Her boys were still boys. Her war was still young.

1861

Arm’d year! year of the struggle!

No dainty rhymes or sentimental love verses for you, terrible year!

Not you as some pale poetling, seated at a desk, lisping cadenzas piano;

But as a strong man, erect, clothed in blue clothes, advancing, carrying a rifle on your shoulder,

With well-gristled body and sunburnt face and hands–with a knife in the belt at your side,

As I heard you shouting loud–your sonorous voice ringing across the continent;

Your masculine voice, O year, as rising amid the great cities,

Amid the men of Manhattan I saw you, as one of the workmen, the dwellers in Manhattan;

Or with large steps crossing the prairies out of Illinois and Indiana,

Rapidly crossing the West with springy gait, and descending the

Alleghanies;

Or down from the great lakes, or in Pennsylvania, or on deck along the Ohio river;

Or southward along the Tennessee or Cumberland rivers, or at Chattanooga on the mountain top,

Saw I your gait and saw I your sinewy limbs, clothed in blue, bearing weapons, robust year;

Heard your determin’d voice, launch’d forth again and again;

Year that suddenly sang by the mouths of the round-lipp’d cannon,

I repeat you, hurrying, crashing, sad, distracted year.

— Walt Whitman[4]

___________________________________

[1]https://47thpennsylvania.wordpress.com/letters-home

[2]https://www.nps.gov/resources/story.htm%3Fid%3D253

[3]http://omeka.wellesley.edu/civilwarletters/items/show/196

[4]https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/1861/

Great primary source excerpts, Meg! Looking forward to the next articles in your series. 🙂

Thanks so much. This was a fun series to do–1861 is my favorite.

Meg

Excellent summation of the arrival of the juggernaut; although, the steady, unstoppable progress of the Nation towards War could also be described by the fall of a line of dominoes, as one by one, each rectangular prism toppled. Did the sequence begin with the Election of Lincoln? Or the attempted Insurrection at Harper’s Ferry? How about the caning of Senator Charles Sumner? Or signing into Law the Kansas-Nebraska Act?

By the end of January 1861 so much had occurred: South Carolina had seceded; PGT Beauregard had been installed as Superintendent of West Point; John B. Floyd had signed an order directing stockpiles of arms held in Pennsylvania be relocated to locations in the South. And President Buchanan, that most energetic of Executives in attempting to hold back the tide, had entered into agreement with Senator Mallory of Florida NOT to resupply Fort Pickens.

Mississippi. Florida. Alabama. Georgia… With each subsequent departure, the fall of each domino, the United States progressed closer to the precipice. Louisiana. Texas. The daily papers explained the situation to the reading public: war was inevitable. And the only two questions: WHERE it would erupt (Fort Sumter or Fort Pickens); and WHO would be responsible for knocking over the Last Domino…

1861 had so much going on. Everything was up for grabs–political, financial, international–to say things settled down would be an odd way to put it, but by 1863 there was much less in flux–except, of course, Copperheads and an upcoming presidential election. lol