Paul Revere and the Civil War

“Listen, my children, and you shall hear, Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere, On the eighteenth of April in ’75, Hardly a man is now alive Who remembers that famous day and year…”

Thus begins Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic (albeit not accurate) version of Paul Revere and his famous ride to warn to the local militias that the Redcoats were on the march. The patriot himself died in 1818, but his memory – interpreted by Longfellow – became an inspiring recruiting tool for the Union cause and helped ensure that Revere’s name would be long remembered and recited.

However, it was not just poetry that connect Paul Revere to the American Civil War. His descendants heard “the hurrying hoofbeats” and the “midnight message” of the Union in peril and rallied to their country’s cause. One of those descendants – a grandson – had vital role in leadership of the 20th Massachusetts Regiment and helped ensure that the family name had a place of honor in the continuing decades of American history.

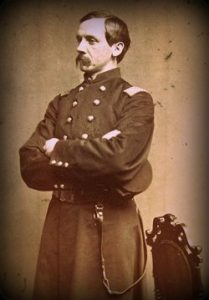

Born on September 18, 1832, Paul Joseph Revere – one of Paul Revere’s grandsons – grew up near Boston, Massachusetts, and attended Harvard University, graduating in 1852. When the Civil War began in 1861, Revere enlisted on July 1 as a major and shortly after received a commission in the 20th Massachusetts Infantry.

Captured at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff later in 1861, Revere spent time in a Richmond prison before his exchange. He served briefly as assistant inspector general for General Sumner and was wounded at the Battle of Antietam. Returning to military service in the spring of 1863, Revere promoted to colonel of the 20th Massachusetts.

The regiment Revere commanded had a bloody history. Nicknamed “The Harvard Regiment” since many of the units officers were young graduates, it had formed at the end of August 1861. Ball’s Bluff initiated the unit in the horrors of war, and afterwards its soldiers fought at most of the Army of the Potomac’s battles, Peninsula Campaign/Seven Days Battles, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Second Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Petersburg, and the Appomattox Campaign. By the end of the war, the 20th suffered 409 casualties, ranking it among the most severely battered regiments of the war.

The Battle of Gettysburg firmly united the name “Revere” in Civil War history. The grandson had recently returned to command, but had not been welcomed back by his subordinates who had wanted another officer with more 1862 experience and regimental knowledge to lead.

Colonel Revere had recently returned to command but wasn’t exactly welcomed back by his subordinates who wanted another officer who had been with the regiment in more 1862 battles promoted to command. However, circumstances placed Revere in charge at a key moment in the regiment’s history and the Civil War struggle.

At the Battle of Gettysburg, the 20th Massachusetts ranked in Hall’s Brigade, Gibbon’s Division, Hancock’s II Corps – Army of the Potomac. This placed them on Cemetery Ridge on July 2, 1863, holding the line while others actively struggled in the III Corps’ collapsing position. The regiment waited, crouching and lying still, while Confederate artillery shells aimed at their position.

While his men lay on the ground, trying to avoid the artillery shells, Colonel Revere stayed upright, walking among his soldiers – encouraging the frightened and recording the dying’s last messages. At approximately, 6 P.M. an artillery projectile exploded overhead and a ball struck Revere, passing through his lungs and deep into his body. Stretcher-bearers carried him off the field to the II Corps hospital. The hurting colonel had enough strength and presence of mind to dictate a telegram to his family in Boston: “Am badly wounded. Come quickly.”

While his regimental boys held the line at the stonewall the following day, taking heavy losses in the repulse of the Confederate charge, Colonel Revere fought for his life. On July 4, he heard the echoing Union cheers and rallied to ask who had won the battle. Someone told him about the Union victory and how Old Glory flew over the battleground. “His eye lighted up with gratitude, and he sunk into unconsciousness.” He did not regain consciousness and slipped away shortly after – perhaps joining his patriot grandfather in the halls of the heroes.

Paul Joseph Revere – a descendant of patriot Paul Revere – fell defending the idea of Union and freedom ignited by his ancestor. His family viewed his death as a patriotic sacrifice that had been Providentially ordained. Considering their traditions and family stories of courage and devotion to the ideals of freedom, Colonel Paul Revere had indeed nobly carried forward their name into a new conflict of American history.

The colonel’s mother wrote in her journal, after news of his death arrived. Her perspective focused on her sons’ sacrifices** but also echoed back to the risks taken by their ancestor on his storied midnight right: “They knew the risk they ran, but the conflict must be met. It was their duty to aid it. The claim on them was a strong as on any and gallantly they answered it.”

Sources and Notes:

**Paul Joseph’s brother Edward had died earlier in the war, also fighting for the Union cause.

The Harvard Gazette – https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2012/03/blue-gray-and-crimson/

Miller, Richard F. Harvard’s Civil War: A History of the Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. (University Press of New England, Lebanon, NH).

Enjoyable article on a hero of the Republic. Thanks.

Well done! By coincidence or destiny, another rider of that April night in 1776, William Dawes, had a grandson Rufus Dawes at Gettysburg, who many know of. As much as Paul Revere’s record outshines William Dawes’, Rufus Dawes record outshines Paul Joseph Revere, so thank you for bringing to light PJR’s record and his undoubted bravery.

Since Paul Revere fathered 19 children, he must have been thoroughly represented in the Civil War.