“Good bye from your soger boy”: One Last Letter before the Wilderness

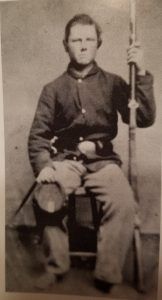

Sometimes he signed his letters “with affection” or “good-night” or “good-bye.” Sometimes he wrote his full name, other times just initials, sometimes with the familiar name to his family and friends: “Will.” Most of his correspondence went to his younger sister “Jennie” and was addressed to the family home in Sebec, Maine. Will had left home in August 1862, enlisting in the 20th Maine Regiment, Company B. He had already survived long months of campaigning and camp life, fought at Gettysburg, and been one of the fortunate ones to recover from a dysentery and a lengthy hospital stay.

On May 3, 1864, twenty-year-old Private William B. Lamson wrote his sister a brief letter. Just another the series of correspondence that had traveled between Virginia and Maine in the past two years. If he had premonitions about his fate in the coming battle, he did not tell sixteen year-old Jennie.

Camp Near Culpeper, Va.

May 3rd, 1864, evening

Dear Sister,

I expect that before you receive this we will be across the Rapidan and no knowing how much farther. We came about 4 miles on Sunday and today 5 or 6.

I know Wm. C. Brown as well as anyone else in this Co. He is a drummer now. I should advise you not to answer that advertisement in the Observer for letters, or any other. The one you speak of was from one of the teamsters who don’t amount to much anyway. When you answer advertisement you needn’t write to me – They only want letters for sport or they can’t get anybody to write that knows them.

I came by that “Miss Terius” honestly, but don’t understand how it ever came on our doorstep at home.

It’s late and I must close. Give love to all.

We’ll soon be in business.

Good bye from your soger boy,

Will

Parts of Will’s letters are cryptic to modern readers though it would have made perfect sense to Jennie. She seems to have asked for advice about writing to other soldiers, and here her older brother advises her to be wary of the guys who just wanted entertainment by writing to impressionable girls. He takes a protective stance even though he is hundreds of miles away.

Will mentions a mystery letter that he had been delivered to home instead of him, but either did not know the details of its origins or did not feel the necessity to explain to his sister. Throughout the past months, Will had repeated asked for information about “the girls” back home, but did not seem to single out one particular lady – casting doubt that this is a reference to a beginning romance.

Militarily, Will does not reveal much here. Common soldiers did not attend war councils and were not informed of the campaign plans. Like his comrades, he knew battles were ahead, but certainly not the details or order of march beyond his brigade. Will correctly surmises that they would cross the Rapidan River.

On the night of May 3, 1864 – probably just hours after his signed and sealed the letter for Jennie – the 20th Maine marched to the riverbank and crossed the following morning at Germanna Ford. Part of General Bartlett’s brigade, General Griffin’s division, V Corps, Army of the Potomac, the regiment headed into the Wilderness.

On May 5, Confederates noticed Union pickets near Saunder’s Field, and Ewell’s Rebels hastily constructed trenches (some can still be seen today) and barricades from tree branches. While the soldiers skirmished, the generals decided. Meade ordered Warren’s V Corps to attack at Saunder’s Field, but it took a long time to get the troops into position.

Private Will Lamson and his comrades in the 20th Maine found themselves in the second line of battle. Pressured by Grant and Meade, the V Corps commanders orders an attack without waiting for support to arrive via the traffic jammed Wilderness roads. General Griffin’s division attacked. By the time the 20th Maine soldiers reached the edge of the open field, the first line of battle was already about halfway across.

Plunging forward, the regiment ran through a firestorm of bullets, but forced the Confederates to abandon the position. Enthused, the Union men pressed forward through the trees to another clearing, only to halt in horror. The 20th Maine got flanked and suffered from the intense Confederate fire. Captain Morrill – who commanded Company B of the regiment – rallied his men and other broken units, managing to briefly halt the Confederate counterattack, giving others time to retreat. This Union attacked failed and the batter regiments fell back, ending one short chapter in the Wilderness’s bloody and intense history.

Will made this charge with the 20th Maine. But it is unclear how far he went or if he fought in Company B’s defense. The Battle of the Wilderness claimed over 100 casualties from his regiment. Will Lamson was one of the fallen.

According to family records and stories, Will died on May 5, 1864 – the same day as the attack on Saunder’s Field. Regimental records suggest he was badly wounded, captured by Confederates, and died shortly after. One comrade later informed the family that he had last seen Will lying under a tree, wounded. Will’s body was never identified or recovered; perhaps he is buried in the Wilderness or in an unmarked grave in Fredericksburg National Cemetery. In the family plot in Maine, a memorial gravestone has been added.

Will Lamson’s last letter to his sister is a reminder of young soldiers far from home. He did not detail a campaign or tell her about boiling coffee. He tried to give brotherly advice. Will knew that “business” (battle) loomed, but he addressed it casually to avoid worrying Jennie. He usually downplayed dangers and battles to her, always trying to shield or protect her from his experiences.

Will’s final moment or hours went unrecorded. The day Jennie received news of her brother’s death also went unrecorded. However, based on evidence through years of letters, it does not seem wrong to suppose that if he was conscious, Will thought about home, about Jennie. He may have hoped Jennie would never know the details about the ending of his life; let her remember him as the soldier brother who wasn’t afraid and who had marched off to war in ’62. Pain, danger from blazing flames, and a deep consciousness of being alone without comrades would have marked the end of his life.

It was late. He had to go. Loving thoughts struggled to hold him longer, for more moments of living. But “business” was over. Somewhere, not far from Saunder’s Field in the dense Virginian Wildenress, Will Lamson – the “soger boy” – had to say a final goodbye to all that he loved and held dear.

“Teamsters don’t amount to much..” LOL. I wonder what the teamsters might have told their sisters about common infantry soldiers? But this is very poignant, and sad. And there are so many similar stories from those times..