The Next Stonewall? Ewell and the Second Battle of Winchester, Part 2

Part 2 of 2. Part 1 is available here.

General Robert Milroy had done little to endear himself to the pro-Southern civilian population in Winchester, Virginia. From curfews, loyalty oaths for food, soldiers quartered in private homes, sets of burdensome rules, communication lockdown, and the strict enforcement of emancipation, Milroy had hit nearly every target to make the local women angry. Amidst their muttered complaints and written abuse heaped upon the Yankee general, a strong current of hope held that Jackson would come back. After-all, “Stonewall” had “saved” them on the never-to-be-forgotten day – May 25, 1862 – when he had forced General Banks and his Yankees out of town.

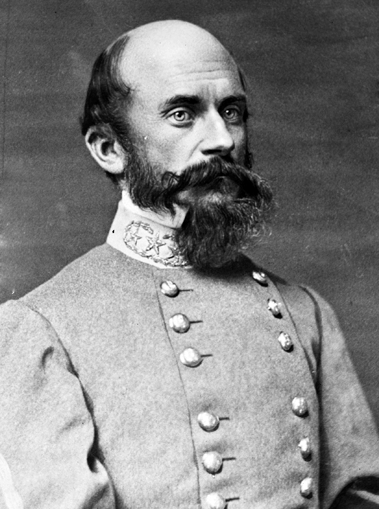

The future looked sad and grim for the Winchester civilians on those anxious May 1863 days when news filtered through Milroy’s censorship blockade that “Stonewall” was dead. Who would save them now? loomed in the minds and journaled pages of the civilians. Pro-Confederate Winchester held an underground hope that someone would come and “save” them from Milroy. On June 13, 1863, their wishes started to blossom into reality. Their new hero – at first glance – might not have seemed as heroic for the legends as “Stonewall”, but “Old Bald Head” would craft a victory just as significant – arguably more spectacular – than his predecessor’s.

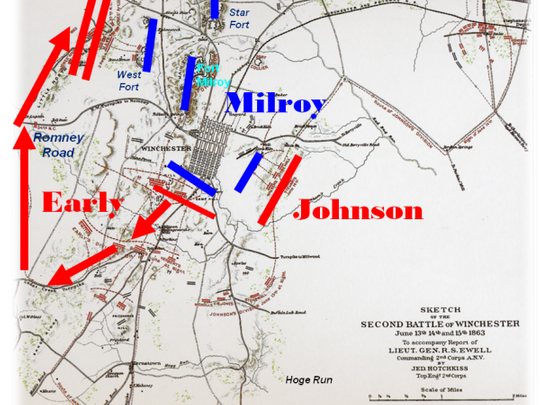

As the leading corps in the Army of Northern Virginia’s marched toward Maryland and Pennsylvania, the Second Corps reentered the Shenandoah Valley. Along the way, Ewell had laid plans with his subordinates – Jubal Early and “Alleghany” Johnson – and took advice from his topographical engineer, Jed Hotchkiss. Their objective: take Winchester and Martinsburg, forcing the Union troops in the lower Valley to retreat or be captured and opening a clear path for the rest of Lee’s army. On June 12th, the corps commander crafted his strategic and tactical moves, relying on his cavalry brigade and infantry officers as he divided his force into two virtually independent forces.

The cavalry under General Albert Jenkins united with General Robert Rodes’s infantry division and headed north, by-passing Winchester and aiming for Martinsburg (West Virginia) via Berryville. According to the plans, they would force the approximately 1,800 Yankees in Berryville to retreat and then rush for Martinsburg which was a supply base and strategic point.

Meanwhile, the remaining majority of the Second Corps would head for Winchester, confronting the infamous General Milroy and hoping to trap his approximately 6,000 troops. Generals Early and Johnson would have to find a way to attack the fortifications Milroy had been preparing or strengthening at Winchester. It would be a different fight than the one the previous year since months of Union occupation had added more defensive earthworks, including Milroy’s ten battery positions now linked by trenches or roads.

Believing his fortification improvements would withstand a Confederate attack, General Milroy waited in Winchester, despite concerns and communications from Washington suggesting an evacuation to Harpers Ferry. To some extent, the Yankee general got surprised; Southern partisan patrols plagued him, forcing him to keep his cavalry closer to town which limited the news of the arriving army pouring through Chester Gap near Front Royal – approximately twenty miles from his fortified city.

Once across the mountains, Ewell accompanied his force heading for Winchester and again divided those units. On June 13, Johnson moved his division down the Front Royal Pike while Early maneuvered farther west and used the Valley Pike for his division’s approach. Skirmishing and small scale fights broke out through the day.

Farther north, Rodes captured a Union supply train and cut communications between Winchester and the “outside world” but failed to trap the units at Berryville which retreated to join Milroy in town. That night a heavy rainstorm soaked the soldiers, cooled the air, and laid down the roads’ dust.

June 14 dawned and Ewell’s men near Winchester readied for a fight. They secured Bower’s Hill – an important piece of high ground – and finalized their attack plans. The corps commander envisioned a double-flank attack, conferred with his generals, and then waited at the vantage point to see the fight that should seal his reputation in his new command. It took most of the day to get the divisions into position, and Johnson deployed skirmishers to distract the Union troops from Early moving onto the west flank of the town. By about 4 p.m., the Confederates had Winchester closely surrounded on three sides – west, south, and east with artillery waiting and infantry poised. Ewell’s orchestrated plan was about to turn Milroy’s reign upside down.

Meanwhile, Milroy spent the day getting reports and observations on the skirmishing and, in the deceptive quiet, believing that the Confederates had pulled back when they saw his forts. Never quite realizing that his enemy had found higher ground and placed artillery and infantry to subdue the supposedly impenetrable fortifications. They also remained blissfully unaware or unconcerned about Rodes’ division poised miles to the north and able to block their last escape routes.

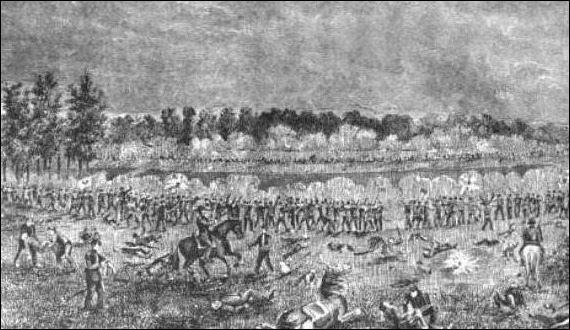

If Ewell had one goal to attack and beat the Yankees as one of his staff officers had observed weeks earlier, he had a golden chance on June 14. And the new commander was in his glory as the attack commenced in the early evening. Around 6 p.m. Confederate artillery opened on Winchester’s West Fort while Early’s infantry snuck close to the fort and rushed the fortifications, forcing the Union men to retreat to Fort Milroy. Darkness fell, but an artillery duel lasted hours with captured Union guns pounding the remaining strongholds on the town’s perimeter.

Ewell’s enthusiasm during the attack had inspired, astonished, worried, and amused his staff and officers who witnessed it. According to Henry Gilmore:

“What a magnificent spectacle met my view!…From the general’s quarters we could see everything going on except round about Early’s force, now going up on the southwestern slope of the heights on which the enemy’s works were built…. The firing was terrific, and yet all of us crowded on the heights to see Early’s charge. We could hear his skirmishes keeping up a continual rapid fire, and occasionally a volley and a yell as he charged some advanced position; and we could tell…that he was getting the advantage. Every piece seemed to be turned on him; but, amid the thunders of thirty or forty guns, there broke on our expectant ears heavy volleys of musketry, and the terrible, long, shrill yell of the two brigades of Louisiana Tigers who were charging up those heights crested with rifle pits and redoubts.

“ The enemy stood firm for a while, and old Ewell was jumping about upon his crutches, with the utmost difficultly keeping perpendicular. At last the Federals began to give way, and pretty soon the Louisianans, with their battle flag, appeared on the crests charging the redoubts. The general, through his glass, thought he recognized old Jubal Early among the foremost mounted, and he became so much excited that, with moistened eyes, he said, ‘Hurrah for the Louisiana boys! There’s Early. I hope the old fellow won’t be hurt. Just then a spent ball struck General Ewell on the chest, almost knocking him down, and leaving a black mark. His medical director, Hunter McGuire, took away his crutches, telling him he ‘had better let those sticks alone for the present.’ He was soon on his feet again, or, rather, on the only one he had left. Early had taken two of the forts….Ewell [at once] named the elevation on which they stood ‘The Louisiana Heights’ in honor of the two gallant brigades that had left so many of their dead and wounded on its side and crest.”[i]

Though thrilled with his troops’ success, Ewell still had decisions to make. Worried that Milroy would try to slip away under the cover of darkness, he ordered Johnson to march his division north and block the Charles Town Road. He had anticipated his enemy’s move; around 9 p.m., Milroy decided to leave Winchester via the Charles Town Road and had his troops abandon the fortifications at midnight. They slipped out silently, leaving Early’s men unaware of their flight. However, Johnson waited.

In the early morning hours of June 15, Milroy and his men stumbled into skirmishers from Johnson’s command. Deploying and prepared to fight their way out, the Union troops found that almost every way they turned Confederate artillery or infantry moved onto the fields or hills to block them. Finally, when the Stonewall Brigade closed the Valley Pike, Union regiments started raising white flags to surrender. Some of Milroy’s units scattered, most surrendered; Milroy himself escaped capture, but had to answer to Washington authorities.

When General Richard S. Ewell arrived in Winchester and news of his victory ran to Lee and Richmond, it sparked a wave of enthusiasm. Jackson had been lost, but a worthy successor to command the Second Corps had been found. Ewell’s victory at the Second Battle of Winchester established him in high command and the success spotlighted some fine leadership qualities.

First, Ewell worked with his division commanders, ordering but also making them part of the strategic process instead of keeping his ideas secret like his predecessor. Second, Ewell wisely held back during the battle and night march – staying close enough to see the fight, but not riding the battlelines; he was apparently in enough danger from the crutches and a spent bullet and sensibly did not further expose himself to dangers. Third, Ewell crafted a superb trap, using the timing of the marches and knowledge of each division’s position to close the door at the right moment.

The Second Battle of Winchester usually gets overshadowed by Gettysburg. Richard Ewell usually gets judged on his actions (or lack thereof) in Pennsylvania. However, Second Winchester marked one of his finest military moments. From the hill, he saw his army surround an entire Yankee army, eventually forcing thousands to surrender and the victory had been secured through his planning and leadership. Ewell had taken lessons from his days as a division commander and honed his personal leadership style and the command pattern for the Second Corps to create one final splendid, sweeping victory for the Confederates at Winchester, Virginia.

He managed to do what Stonewall did not – trap the Union army by controlling the roads to the north. In that sense, Ewell arguably secured the greater and more complete military victory. The capture of Winchester and defeat of Robert Milory added to the morale wave experienced by the Army of Northern Virginia. It fostered their ideas of strength and invincibility which carried them forward to northern soil once again.

In the end and in the broad interpretation of Civil War history, the Second Battle of Winchester tucks into the Gettysburg Campaign – often forgotten, rarely mentioned in generic explanations. However, the battle’s implications added a significant chapter to the Confederate experience during that campaign which influenced their attitudes and actions at the big battle in Pennsylvania. It created fear among the Union civilians and military. It added another victory name to the banners of the Second Corps. It crafted another legend of deliverance for the local civilians in Winchester.

And – for Richard Ewell – the Second Battle of Winchester marked his military threshold where he transitioned from division to corps commander in the battlefield sense and where he proved that he could secure victories as great – or even greater – than Stonewall. With one smashing success behind him, he rode northward with his corps, looking for greater moments during the second invasion of the north. Never knowing that his first large battle as a corps commander would be his finest moment and that his victory would be often forgotten in the shadow of his indecision at a little town called Gettysburg.

Source:

[i] Harry Gilmor – quoted in: Wheeler, Richard. Witness to Gettysburg: Inside the Battle that Changed the Course of the War. (1987). Stackpole Books, Gettysburg: PA. Pages 49-50.

Great post, Sarah. I always think of this as the perfect small Confederate victory, just as Bristoe Station would be the perfect little Union victory. It most definitely would lead Lee to overestimate the degree of independent initiative that Ewell would show on the First Day.

Ewell was in independant command at Winchester but was back under Lee’s authority at Gettysburg. I think his indecision was the product of being used to Jackson giving direct thorough orders that left no leeway wheras Lee’s order to take the hill was discrestionary. My two cents.

I think that’s a valid point regarding Lee’s orders. I would add that Lee’s multiple orders to Ewell were to some extent conflicting and that Lee was never proficient at drafting clear orders – unlike others, including Grant.

Another fine article Sarah. If only Ewell had acted on that 1st day of Gettysburg, things may have been different and the people of the South would of had their independence that they fought so honorably for.

The myth continues. How about some details regarding the condition and organization of Rodes’ division by early evening on July 1; the condition and organization of Early’s division by that time; Early’s input to Ewell about what his division was capable of;; the Union strength and alignment at that time; Lee’s refusal to give Ewell Anderson’s division as requested support on his right; Lee’s conflicting orders to Ewell; and the whereabouts and arrangement of Johnson’s division. Ewell on July 1 became a scapegoat after the War for the crowd that simply could not handle an honest appraisal of Lee’s decisions during the three days of Gettysburg. In that realm he joined Longstreet. Ewell would later fail to rise to the task of corps command but the legend of July 1 is just that. .

If only… that’s some very wishful thinking. The war didn’t and wouldn’t have come down to what Ewell did that evening.

Lee wasn’t going to destroy the AotP that day. If Ewell had somehow routed the Union forces on Cemetery Hill that evening, Meade would have simply fallen back to his defensive line at Pipe’s Creek to fight on.

The Confederacy’s best shot at winning was probably as E.P. Alexander thought, and that was immediately after First Manassas, but of course the Confederacy didn’t have the ability to support any kind of effort to take Washington at that moment in time.

Lee’s best shot was probably when McClellan was in front of Richmond. If he could have annihilated the AotP or most of it there, that might have created enough political problems for Lincoln to open peace negotiations.

Those are solid points on the “big picture”. And Ewell was very, very unlikely to rout the forces on Cemetery Hill that evening for the numerous reasons I’ve stated. My favorite quote from this entire event is Trimble’s alleged boast that he could take the Hill with a “regiment”. There were 41 Union guns in place and about 9500 troops at the start, growing to about 12,000. If Trimble in fact made that comment, somebody should have searched his saddlebags for hallucinogens.

I should add… I don’t think the Confederacy could have won as long as Lincoln was President. Lincoln was a fighter and wasn’t going to give up.They needed to have done well enough to see Lincoln lose to a Democrat in 1864. They simply didn’t do well enough to have this come to pass.

Great posts about him. I was just in Winchester and New Market earlier this week. I’ve always thought of Ewell as being quite competent given what he had to work with, i.e., always seeming to be out numbered when part of Lee’s army. With the rare edge in manpower on his side at Winchester he delivered a victory. I also think Ewell gets a bad rap for what transpired at Gettysburg. I am no expert on him or his life or career, but I am not aware of any instances that showed him to ‘lose his nerve’ or not display courage and fortitude.

Exactly! Ewell takes command at a less-than ideal moment which really shows after Winchester. As Kris and Chris so often point out, the losses at Chancellorsville were irreplaceable for the Confederacy and Ewell will have to take shrinking corps size into account in all his battles. Thanks for highlighting the troop numbers.

Gettysburg? Ugh – personally, I think hindsight is a real problem when thinking about Ewell’s decision to not occupy Culp’s Hill. We can all figure out NOW what he should have done. However, in that moment, there was so much he had to factor, including deciphering what Lee wanted in the “if possible” orders. Sources point to him trying to make a wise decision, not throwing up his hands and saying “fine, I don’t have to go.”

Sarah: Those are good points. If anything is definitive about this (“if”), it seems that Ewell’s one error regarding Culp’s Hill may have been deferring to Early, who vehemently objected to having his division attack that position. That, coupled with Johnson’s carping about his division being delayed by wagons, etc. almost certainly led Ewell to decide against the attack. (We know that Rodes’ division was hors de combat for the moment). For a host of reasons, the earlier decision not to attack Cemetery Hill is hard to criticize. Overlaying all of this are Lee’s contradictory orders to Ewell and his refusal to provide Anderson as support. And, regarding Culp’s Hill, if your lead division commander strongly opposes the tactics, do you simply tell him to “stick it” and follow orders? That may be where Lee’s ambiguity played a role.

Thanks for this post; it’s cool to read about 2nd Winchester on the anniversary. My 3x great-grandfather, a member of the 6th Louisiana, was wounded in the charge on West Fort that day.

Joel Manuel

Baton Rouge

Thanks for sharing this, Joel.

Have you had a chance to visit the preserved parts of the battlefield? Shenandoah Valley Battlefield Foundation lists West Fort as a tour stop. Here’s a link: http://www.shenandoahatwar.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Second-Winchester-Driving-Tour.pdf

Sarah- not yet. I’ve lived in LA all my life and have only driven up that way once, and wasn’t aware that I had an ancestor who’d fought there. It’s definitely on my bucket list, though. That, and Patsy Cline’s grave. 🙂 btw my ancestor was Alfred Young, Company C, 6th Louisiana Infantry.

JM