“Old Rock” Benning’s Georgia Brigade at Gettysburg and Those Three Northern Guns Captured on July 2

Forty years ago, as a doctoral graduate student at Emory University, I received invitation to write about several Confederate generals for The Dictionary of Georgia Biography (2 vols., Athens, 1983).

One of those whom I chose was Henry Lewis Benning, of Columbus, Ga.

Born in Georgia in 1814, after college Benning studied law and was admitted to the bar of Columbus. As a state rights advocate he attended the Nashville convention of 1850 and introduced resolutions defending slavery and endorsing secession. He served six years on the Georgia Supreme Court. At the Democratic convention of 1860 in Charleston he led the Georgia delegation out when Southerners could not get a slave-code plank adopted into the party platform.

After Lincoln’s election, he called for Georgia’s secession. When war broke out, he raised the 17th Georgia Infantry and was elected its colonel in mid-August 1861.

Benning and his regiment served throughout the war in Virginia. By Second Manassas he had earned the nickname “Old Rock” for his coolness and bravery on the battlefield. At Sharpsburg his Georgians helped delay Burnside’s crossing of Antietam Creek.

Colonel Benning was promoted to brigadier general on Jan. 17, 1863. As part of Hood’s division, he was detached to Suffolk, on southeast Virginia, and hence missed Chancellorsville.

But Old Rock and his brigade were very present at Gettysburg.

When I was an undergrad at Emory, the Kappa Alphas had a cheer.

“How many Yankees are there?”

“TEN THOUSAND!”

“How many KAs are there?”

“THREE!!”

“What’re we going to do?”

“CHARGE!!!”

Well, on July 2, Union Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles had about 10,000 men in his III Corps, which Hood’s division, including Benning’s brigade, attacked that afternoon.

Here’s how it shaped up.

Based on scouting reports early on the morning of July 2, General Lee concluded there was no enemy force south of Cemetery Hill. He therefore ordered Longstreet’s two divisions (Pickett had not come up) to get in position astride the Emmitsburg Road, well south of the hill, and advance in an oblique against the Federal left.

The problem, though, was that in the time it took for Longstreet to get his troops in place—it took hours on end—Union Maj. Gen. Dan Sickles (instead of extending Meade’s left along Cemetery Ridge) advanced without orders to higher ground in front of the ridge, into Joseph Sherfy’s peach orchard and, to its south, a large rocky area called Devil’s Den.

The Yankees’ new position threatened Hood’s division, which had become the extreme right of Lee’s long line. Before 4 p.m. Hood’s scouts then brought word that there was no enemy on Round Top and that an advance in that direction could allow Hood to outflank the Federal left at Devil’s Den.

Hood accordingly sent officers several times to General Longstreet asking for a change of orders. Pete refused and ordered Hood to launch his attack as planned. Hood said to Lt. Col. Phillip Work, commander of the 1st Texas, “Very well. When we get under fire I will have a digression”—meaning an advance toward Little Round Top, not up the Emmitsburg Road. But a shell burst overhead, sending a ball into Hood’s left arm and taking him out of the battle just as his assault began a little after 4 p.m.

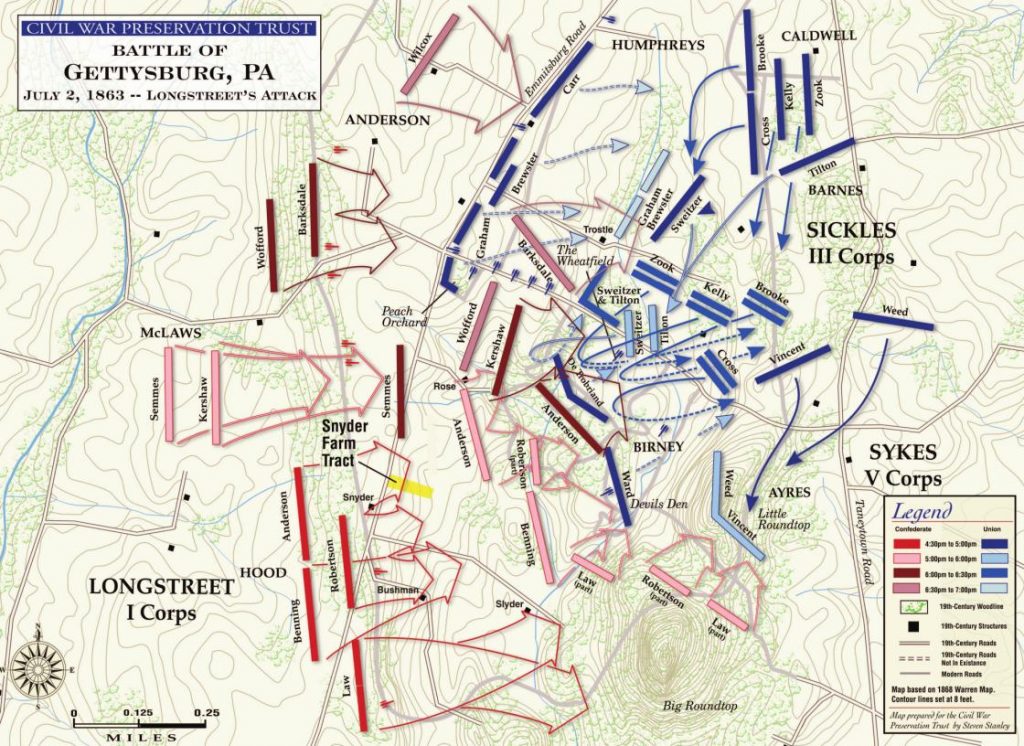

Evander Law, senior brigade leader, took over division command as Hood’s four brigades advanced against Devil’s Den and Round Top. Law’s and Jerome Robertson’s Texas Brigade formed a nine-regiment front. In a second rank were Benning’s (on the right, or to the south) and George “Tige” Anderson’s. The fine maps in Harry Pfanz’s Gettysburg: The Second Day (1987) shorthand the action. Law’s brigade crests Round Top and pushes toward Little Round Top. Robertson and Benning charge the Yankees at Devil’s Den while to Benning’s left Anderson advances on Rose’s Woods, south of the Wheatfield. Benning and Robertson drive the Federals from Devil’s Den.

A cool feature of the maps in Noah Andre Trudeau’s Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage (2002) is that Andy has little clocks on his maps to show at what time of day the action is depicted. 4:50 p.m. Benning and Anderson approach Devil’s Den and the Wheatfield. About an hour later, by 5:45 p.m., Benning, Anderson and elements of Robertson have taken Devil’s Den and their line stretches north of the Wheatfield. Trudeau comments, “It appeared that the Rebel effort to overwhelm the Federal flank had failed save for Devil’s Den” (p. 367). By this time, around 6 o’clock, Longstreet’s attack has been taken up by McLaws’ Division to the north.

“The peak being thus taken and the enemy’s first line driven behind his second,” General Benning wrote in his campaign report, “I made my dispositions to hold the ground” (OR, XXVII, 2, p. 415)

From Seminary Ridge to Devil’s Den, west to east, is about ¾ miles. For this ground gained, the cost to Benning’s Brigade was steep. In about two hours of combat, as counted by Trudeau, the brigade lost 519 officers and men out of 1,420 going into the fight. That’s a casualty rate of 36%.

Hood always told his troops that flags and guns captured were the finest trophies from the battlefield. In the fighting at Devil’s Den the 1st Texas and 20th Georgia took three 10-pounder Parrotts of Capt. James Smith’s 4th New York Battery. So it was understandable that commanders of the two regiments tussled as to who won the honors.

Smith had six Parrotts; General Benning in his after-action report stated, “we captured only the three front guns.” On the contrary, Lieutenant Colonel Work of the 1st Texas reported that “I sent three pieces of the artillery captured to the rear.” Benning’s biographer, J. David Dameron obviously sides with his Georgia troops in the taking of the guns, “perhaps winning the only Union artillery captured in northern territory” during the war (General Henry Lewis Benning: A Biography of Georgia’s Supreme Court Justice and Confederate General [2004], 175). Wrong: L. VanLoan Naisawald, in Grape & Canister: The Story of the Field Artillery of the Army of the Potomac, 1861-1865 (1999) counts seven Yankee cannon captured by Lee’s troops at Gettysburg (p. 351).

The Texans held on to their claim to the New Yorkers’ three Parrotts. One Texan swore that he heard General Benning himself telling his men, “Ah, boys, those Texans had captured this battery before you were in a quarter of a mile of here” (Susannah J. Ural, Hood’s Texas Brigade: The Soldiers and Families of the Confederacy’s Most Celebrated Unit [2017], pp. 159-60).

“Old Rock” Benning is better remembered for what he called out to his Georgians as he paced behind them, urging them forward in their advance. “Give them hell, boys,” he yelled, “give them hell!”

They surely did.

An interesting article. In his report following the battle, Smith stated that he could have brought the three guns with him when he limbered the others, but that he expected the supporting infantry to defend them so that he could return and put them back in action.