The Trust’s 2019 Teacher Institute: The Great Humanitarian Crisis of the War—Civil War Prisons

As a college professor, I don’t have to sit through many lectures (and I seldom, if ever, actually give any, preferring discussion-based lessons instead). So, it’s been a while since I’ve sat through a lecture and even longer since I’ve sat through one I really enjoyed. My ECW colleague Derek Maxfield gave me that pleasure yesterday afternoon, which is a little ironic considering the grim nature of his topic.

As a college professor, I don’t have to sit through many lectures (and I seldom, if ever, actually give any, preferring discussion-based lessons instead). So, it’s been a while since I’ve sat through a lecture and even longer since I’ve sat through one I really enjoyed. My ECW colleague Derek Maxfield gave me that pleasure yesterday afternoon, which is a little ironic considering the grim nature of his topic.

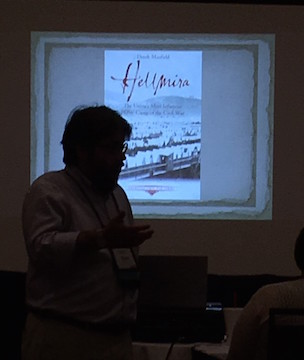

Derek spoke at the American Battlefield Trust’s 2019 Teacher Institute about a topic that stems from his upcoming ECWS book Hellmira: The Union’s Most Infamous Prison Camp of the Civil War. Specifically, he called prisoner of war camps “The Great Humanitarian Tragedy of the Civil War.”

“This a dark corner of the Civil War,” he told the audience. “It’s one of the darkest corners of the Civil War.”

It’s dark, he said, because of the subject matter, but it’s also dark because the light of research has not really illuminated it yet. “This is one of the things that has surprised me along the way,” he said. “It’s even more of a hidden topic than I thought it was. The amount of scholarship out there is miniscule.”

Derek said he had a personal connection to Elmira’s story. “I’m a true-blue Yankee,” he admitted. “I had six great grandfathers who served in the war—all of them wore blue. Four of them survived.” One of them, William B. Reese, was wounded at Gettysburg, then served in the Veterans Reserve Corps and finished out his service in Elmira. “He may have played a role in guarding the prisoners there,” Derek said.

Derek grew up 40 miles north of Elmira, but he nonetheless had no clue there was a Civil War camp in the area. “It was not until college before I made that discovery, and I was in Elmira all the time,” he said. “That’s because there were no visible remains of the camp.”

Only years later did he discover the communal act of forgetting that consigned the Elmira camp to obscurity.

“History is about memory: how we want to remember,” he said. “And it’s also not just what we remember but also about how we want to remember it.”

“History is about memory: how we want to remember,” he said. “And it’s also not just what we remember but also about how we want to remember it.”

“In Elmira, it was a collective effort,” he explained. “They wanted to erase it because it was being compared to Andersonville. Everyone in the country knew about the notorious prison at Andersonville, and Elmira became the Union equivalent in Southern eyes. “Every time Andersonville came up, Southerners would counter with ‘What about Elmira?’”

“I would argue that the experiences were not quite the same,” he added—and would go on to do just that—“but who wants to be equated with Andersonville?

It was bad for business, bad for tourism. “Sometimes, history is not just a matter of memory but a matter of capitalism,” he said.

Finally, in 1992, a monument to the camp finally went up, tucked away by an old water works. “But you had to know it was there, because there were no signs pointing people to it,” Derek said.

And thus, Elmira’s prison camp history languished for well over a century and a quarter.

During the course of the war, North and South held some 400,000 soldiers in more than 150 facilities. Of them, some 56,000 men died during their incarceration. “And I would argue that number is very low,” Derek added. “Plus, what happened to the men who died as a result of their incarceration after the war? Those numbers will never be known.”

As horrible as those numbers are, Derek argued that the POW story gets buried in the context of the larger horror of the war, where as many as 750,000 people died—“and that number may even be low,” he said.

What makes POW deaths—and the POW story—particularly tragic is that it all might have been preventable.

“While you are holding prisoners, do you have any responsibility for their welfare?” Derek asked. “This is something you have control over. Both sides. Both sides control the location of their prisons. Both have control over resources. Those are things that you can control. Both sides failed—and that is why so many men suffered.”

Elmira’s story began with Lt. Col. William H. Hoffman, the Union commissary general of prisoners, appointed from obscurity early in the war to head up efforts for holding prisoners. “If this was something you really cared about, you would not get a penny-pinching nobody to be in charge of it,” Derek said.

A “primitive” POW exchange program got underway, but Shiloh created a POW emergency because of the sheer quantity of men involved. That jump-started further improvements to the system, but then the Emancipation Proclamation threw the entire system into turmoil. Black soldiers, said Confederate Secretary of War Seddon, could not “be recognized in any way as soldiers subject to the rules of war or and to trials by military courts.”

That, in turn, led to the breakdown of the exchange system.

Another change came when Grant launched the Overland Campaign in the east in the spring of 1864. “This turns into one long six-week battle,” Derek said. “Aside from the number of killed and wounded, there’s a tremendous number of captives.” Rather than exchange those captives, Grant’s plan to use up the Confederate armies meant he wanted to hold on to prisoners so they would not return as reinforcements. “It is hard on our men held in Southern prisons not to exchange them, Grant admitted, “but it is humanity to those left in the ranks to fight….”

Derek outlined various types of POW facilities: existing jails/prisons; coastal forts; old buildings; barracks enclosed by palisades; clusters of tents enclosed by palisade; barren stockades; barren ground (a line of sentries make a circle, not meant to be anything but temporary).

“Andersonville was a big pen,” he said by way of example. “You have a big fence and you put people inside it. The number of these stockades that went up became alarming.”

At its peak, Andersonville held almost 40,000 men, although it had been built to only hold 10,000. With these numbers, Derek started to draw contrasts—rather than the stereotypical comparisons—with Elmira.

Formally called Camp Chemung, named for the river that runs through Elmira, the 50-acre camp in western New York existed from July 1864-65. “Why Elmira?” Derek asked. He pointed to the dependable, accessible transportation that could move POWs and supplies in and out of the area. There were also facilities already there, the Arnot Barracks, which had been used as a mustering station earlier in the war and as a draft rendezvous later in the war.

New facilities had to be added, but “the barracks were made of green wood, which split as soon as the freeze came in the winter,” Derek said. Construction proceeded without much urgency. “You had men lying on the ground on straw in January, when there’s snow on the ground.”

Twice during the war, rations were cut. “This was about retribution, not resources,” Derek said. This raises additional questions about the moral obligations both sides felt, or didn’t, toward the men they held in captivity.

While Lt. Col. Seth Eastman served as the rendezvous post commander—in effect, the first commander of the prison— Maj. Henry V. Colt ran the camp on a day-to-day basis. Recovering from injury in battle, he’d been assigned to oversee camp while convalescing.

Elmira’s prison camp hosted about 10,000 prisoners at any one time. Over the course of its existence, some 3,000 men died altogether. The overall casualty rate was about 24%—the highest of any northern prison camp. Andersonville’s, Derek said, was 29%, which is why Elmira is compared to Andersonville.

“But the number of actual dead at Elmira is way overshadowed by the number of dead by Andersonville,” Derek pointed out, citing a figure of more than 12,900. That’s why comparisons between the two camps break down.

Most accounts of the horrors of Elmira were written 20-30 years after the war, Derek said. “They’re filled almost universally with vitriol,” he added. However, he also pointed out that, by then, the accounts had been strongly influenced by postwar arguments about Andersonville. “So they’re biased,” he concluded.

The one exception came to Maj. Colt. “Anyone who mentions Colt loves him,” Derek said. “Confederate POWs like this man—really like this man.” By the time Colt completed his convalescence and went back to the front in January 1865, the prisoners presented him with gifts.

He questions the authenticity of postwar accounts when, at the time, soldiers seemed to exhibit much different attitudes. “Their [postwar] accounts would say, ‘It was awful, it was dreadful, they treated us worse than animals—but we loved this man,’” he said, stressing the contradiction. “There’s something there.”

He also noted that dozens of Confederates held at Elmira came back after the war to visit, and at least five moved to Elmira to live.

After the war, the camp vanished without nary a trace. “The Army’s contract said the land would be returned to the owners just the way it had been before the camp was set up,” Derek said. “Buildings were deconstructed and sold off.” The city’s process of intentional forgetting began.

A reconstructed building, made from the lumber of one of the original prison buildings, now sits on the site. “The windowpane and hardware are original,” Derek said. “Seventy percent of the materials are original.” A barracks has now also been reconstructed based on schematics found in the old War Department.

Nearby, in Elmira’s Woodlawn National Cemetery, the 3,000 Confederate dead lie interred, buried there by a former slave.

“One of the challenges we always have with students is, ‘How do we make this relevant to them?’” Derek said, heading into the home stretch. He suggested several questions to consider:

- What is the purpose of holding POWs?

- What is the nature of that confinement?

- Deprivation of liberty vs. continued punishment

- What responsibility do authorities have to the prisoners?

As he thinks about making that relevant to students today, he recounted a year he spent teaching at the prison in Attica, New York. “I wonder about incarceration today, and the parallels,” he said. “What is the purpose of incarceration of criminals?

“We should have a conversation about what the point is, and whether we have a responsibility to the prisoners,” he concluded.

————

Here’s more on “Hellmira” at ECW:

Reconstructed prison building taking shape at “Hellmira”

“Hellmira”—a Place of “Terrible Memory,” Nearly Forgotten

I recommend everyone interested in this topic read the U.S. National Cemetery Administration (part of the Department of Veterans Affairs) study titled “Federal Stewardship of Confederate Dead.” I retired from NCA in 2011 and was once a speaker at the Memorial Day ceremony at Woodlawn National Cemetery (it’s not named “Elmira National Cemetery.”) The ceremony was well supported, including music from a local high school band, in spite of the atrocious weather. In fact, in 1997, local students raised money for a monument to sexton John W. Jones, the escaped slave who oversaw all the burials of the Confederate prisoners and conscientiously recorded all their names and units and ensured that they were painted on headboards marking their graves. In the 1870s the local upstate NY congressman lobbied to force the Army to instal permanent stone markers for the Confederate graves as well as the Union graves. That wouldn’t happen until around 1910 but photographs show that local citizens decorated both Union and Confederate graves as early as 1875. In 1912 the commingled remains of Confederate prisoners and Union guards killed in an 1864 train wreck en route to Elmira were disinterred and buried at Woodlawn National Cemetery where a monument to both was erected over the common grave. In 1937, the United Daughters of the Confederacy erected a monument to the Confederate dead. In recent years, dating from the 1980s, re-enactors and living history encampments have drawn attention to the history of the camp and the cemetery. It doesn’t seem that the history of the prison camp was intentionally forgotten.

Here’s a link to the National Cemetery Administration study. https://www.cem.va.gov/CEM/publications/NCA_Fed_Stewardship_Confed_Dead.pdf

The section on Woodlawn National Cemetery starts at page 221.

The study of POWs and prisons lacks the sex appeal of Civil War battles and commanders. And at the time, many believed “the prisoners brought misfortune upon themselves by surrendering.” Upon release from captivity, many had to fight to clear their reputations due the stain of surrender.