A Conversation with Author Robert Conner on Grant’s Dying Days

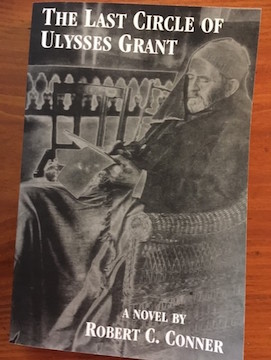

One hundred and thirty-five years ago today, Ulysses S. Grant died on Mt. McGregor in Wilton, NY, just north of Saratoga Springs. Just days earlier, he had completed the draft of his memoirs. Robert Conner is a guide at the site, now known as Grant Cottage, which is administered as a New York state historic site and operated by the Friends of Grant Cottage. Last year, Bob published a novel about Grant’s time at the cottage, The Last Circle of Ulysses Grant. Earlier this month, I had the chance to correspond with Bob about his novel. (The following interview has been edited lightly for clarity.)

One hundred and thirty-five years ago today, Ulysses S. Grant died on Mt. McGregor in Wilton, NY, just north of Saratoga Springs. Just days earlier, he had completed the draft of his memoirs. Robert Conner is a guide at the site, now known as Grant Cottage, which is administered as a New York state historic site and operated by the Friends of Grant Cottage. Last year, Bob published a novel about Grant’s time at the cottage, The Last Circle of Ulysses Grant. Earlier this month, I had the chance to correspond with Bob about his novel. (The following interview has been edited lightly for clarity.)

Chris Mackowski: As a tour guide at Grant Cottage, you’re well familiar with the story of Grant’s last days. What is it about the story that appeals to you so much?

Bob Conner: Grant was dying from throat cancer and in increasing pain and weakness as he struggled to finish his memoir. He’d never written a book before. He was also heavily in debt, and his prime motivation was to dig himself and other family members, especially his beloved wife Julia, out of the financial hole he felt he’d put them in. The result, the book published after his death, is not just the best presidential memoir ever written, but a profound (and sometimes funny) work about the Civil War, the Mexican War, and 19th century America. How he pulled it off is an extraordinary tale.

CM: Why did you decide to write a fictional account of those last days?

CM: Why did you decide to write a fictional account of those last days?

BC: My first book, and my third (which I am writing now), are nonfiction biographies of somewhat obscure Union soldiers. Grant is anything but obscure, and there is plenty of good history written in recent years (including by you) about the end of his life. Fiction, though, allows you to do something else, to try to dig down to truth through a kind of glorified guesswork. So a novelist can seek to get inside Grant’s head, and illuminate the lives of other real people, famous and obscure, and how they may connect with each other and the history of their time.

CM: Of the biographical writing about Grant you mentioned, do you have a favorite?

BC: Favorites from that period include works by Frank Scaturro, Jean Edward Smith, Charles Bracelen Flood, Mark Perry, Joan Waugh and Chris Mackowski. I also used plenty of older sources, but the moderns tend to have a clearer appreciation of Grant’s political achievements, including a more positive view of Reconstruction. I hear good things about the Ronald White biography, but haven’t read it yet. I have read Ron Chernow’s, but it came out after I had finished the novel.

CM: What did you think of it?

BC: I liked it. I was pleased to see Chernow sharing some of my own views, e.g. acknowledging the significance of Grant’s drinking problem (which some of his defenders refuse to admit). I was also pleased to see Grant portrayed as a standard, not particularly devout Methodist, rather than the agnostic or even atheist that some of his modern admirers claim to see. And Chernow made me understand why Grant felt betrayed by Elihu Washburne in 1880. I differ from Chernow’s apparent view that Grant was an artistic Philistine, and wish he had written more about the president’s efforts to avoid war with the American Indians and with Spain over Cuba.

As for the last months of Grant’s life, the focus of my book, I detected one error in Chernow’s (page 952), in which “a lock of Jesse’s hair” was actually Buck’s, i.e. Jesse’s older brother. The hair had been clipped from Buck’s infant head by Julia, entwined with her own and sent to Lieutenant Grant on the Pacific Coast, before he’d ever met the boy. It was found after his death in the pocket of his robe, along with a farewell note to Julia.

CM: How long did it take you to write your novel?

BC: It took about 20 years for the project to come to fruition, but obviously I was doing many other things during that time. It started out as a play, which I set aside, then picked up years later after my biography of Gordon Granger was published in 2013, and decided to turn into a novel. I changed the plot from the play, making it more realistic and less melodramatic, and added a lot of material. Much of the action was moved to New York City.

CM: Where does the title come from?

BC: The title deliberately leaves out the middle initial of Grant’s name (which wasn’t his real name anyway), because that’s too formal for friends to use. And the book is as much about the people around Grant, and the America around them all, as it is about its hero.

CM: You start the book in May of 1885 by recapping events a year earlier, when Grant’s investment firm failed. What was it about that moment in time that made you want to start the story there as opposed to somewhere else?

BC: The book does flash back a good deal, especially to the war years, which I think is natural for a dying soldier and his aging comrades. But I focus on a five-and-a-half-month period, from the end of March to September 1885, which includes Grant’s last months and the aftermath of his death, when the surviving characters find their own ways forward. Badeau’s betrayal and Grant’s resistance to it fall in the center of the novel and is the most purely historical part of it, with their actual letters to each other the hinge on which the book turns.

The backstory starts in 1884 because that was a catastrophic year in Grant’s life. First he discovered he was not, as he had thought, a rich man, but due to the fraud of a business partner had been left heavily in debt. Then he was diagnosed with inoperable cancer. Grant’s courage in grappling with these twin disasters is the foundation of the story.

CM: Do you have a favorite character in the story?

BC: My favorite characters include three who gather together in a Manhattan restaurant near the end of the book: Nellie Grant, Ely Parker and Frank Herron. But I also have a soft spot for the anti-hero, Adam Badeau, despite his indefensible conduct and clouded vision. He gets the last word.

CM: What was it about them that appealed to you so much?

BC: Nellie, who turns 30 in the course of the book, is generally seen as Grant’s favorite child. She was trapped in a bitterly unhappy marriage and had temporarily left her three surviving children in England, where she lived, to be with her dying father and the rest of her American family. She is able to help them, and interacts successfully with the new currents of life she finds in 1885 New York, including forceful and independent women with whom she shares some qualities. She also draws from her parents’ courage as she girds herself to face what she must deal with across the Atlantic.

Ely Parker is an important person in Grant’s life and American history, the first Indian to play a substantive part in the national government. He was, by 1885, conflicted about the roles he had played, and the historical record says that he was refused entry into Grant’s house on one occasion as the general lay sick. That last incident may not have much significance, but I give it some in the novel, and invent—plausibly, I think—a role for Parker as the secret go-between who helps contain a scandal that was actually concocted by a man he knew well, Adam Badeau, a fellow longtime-member of Grant’s military staff.

Frank Herron functions as a sort of everyman, mostly forgotten despite his meteoric rise to major general early in the war, and his significant role in the Reconstruction politics of Louisiana. By 1885, having raised his wife’s children by her prior marriage, they are now bringing up a grandson, while he makes a not-particularly secure living as a New York lawyer. He also suffers bad dreams from the war.

CM: What did you learn about Grant by tackling his story this way?

BC: There has been lots of good biographical writing about Grant in the last 20 years or so. Writing this book was an incentive to read it, which deepened my knowledge about and admiration for him.

CM: Is there someone else you got to know, by writing this story, that you came to better appreciate or understand than you previously had?

BC: I knew very little about Frank Herron (the youngest major general in the US Army before George Armstrong Custer was promoted) until I wrote the book. I thought briefly about writing his biography instead of this novel, until I discovered a detail about his war record that I didn’t know how to deal with. I think it profoundly affected his life, but doubt there is any documentary evidence of that, so it became part of a conversation in the novel.

As a young major general, he has haunted eyes in a well-known wartime photograph, which I think may be related to an incident when he was a brigadier at the beginning of the battle of Prairie Grove, in Arkansas in 1862. Arriving after a forced march from Springfield, Missouri, Herron discovered his cavalry in panic-driven flight. He stopped them by killing one of his own men, shooting him out of the saddle. I didn’t know how to deal with it in a biography I had briefly contemplated writing of Herron, but used fiction instead to imagine how that and his other experiences of combat might have affected his later life.

CM: What do you hope readers will take away from the book after they finish it?

BC: I hope readers will take pleasure in the many amazing stories of the Civil War era and beyond, including the last months of Grant’s life, and how they may link up our understanding of America.

CM: Do you have any advice to folks who might be considering a visit to Grant Cottage to see the place where the events of your novel take place?

BC: Whether or not you read my book, come see Grant Cottage. It’s a wonderful place and story, and I might be around to give you a tour.

CM: How long have you been a guide at the cottage?

BC: Only 10 years, though I first started coming to the cottage in 1983, when my then-girlfriend (now wife, to whom the book is dedicated), noticed the legendary caretaker Suye Narita Gambino working in the garden there. Not long after that, I was writing newspaper stories about the state of New York’s attempt to close the cottage, thwarted by locals who went on to found the Friends of Grant Cottage organization that now runs the site in collaboration with the state. I brought my kids and other people there over the years, and soon after starting to volunteer was hired as a staff member—site interpreter—for a couple of seasons. Then I went back to occasional volunteering, which I continue to do.

CM: Is there anything I haven’t asked that I should have or that you’d like to touch on?

BC: Being set in 1885, the book looks not just back at the Civil War and Reconstruction but at other contemporary issues, such as women, immigrants and Indians looking to find their way in a changing America. All of these linked themes continue to resonate down the years.

CM: If people want to buy the book, how can they get a copy?

BC: The book (which is not self-published) can be ordered through the publisher, Square Circle Press, and is also available through the usual online retailers such as Amazon. I hope you can also find it at Grant Cottage (they were almost sold out when I was there on July 7).

————

For more from Bob, check out his blog at robertcconnerauthor.blogspot.com.

1 Response to A Conversation with Author Robert Conner on Grant’s Dying Days