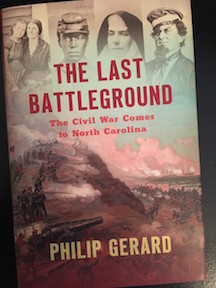

A Conversation with Philip Gerard on The Last Battleground (part two)

Yesterday, we began a conversation with author Philip Gerard about his excellent new book The Last Battleground: The Civil War Comes to North Carolina (UNC Press, 2019). “I started out knowing pretty much nothing about the war,” Philip said, “and what I knew turned out to be wrong for the most part.”

Philip Gerard: The typical story you get is the “Ra-ra. We’re gonna lick ya. We’re the North. We’re the party of justice for blacks”—and the racism in the army and resistance to having black soldiers was another eye-opening surprise. Sherman was running a military school in Louisiana before the war; he was fine with slavery. Grant had no use for black soldiers, and yet those two probably played the biggest roles out of everybody in helping free enslaved people and make it possible for black troops to fight in battle. It’s really interesting to see the contradictory things that wind up happening. Grant was a Democrat. Sherman didn’t vote for anybody.

That became the rabbit hole of fascination. Everything that I would go in to thinking I had a steady point of reference on it—it turned out that really there was a twist to it, an exception to it, some nuance in what happened.

Even something you would think is a rock-solid fact like the number of people that died at a certain battle is a moving target. Three different stories give three different accounts, the roster shows you different, eyewitness accounts show you different, and it’s like we’re all counting it differently somehow.

I remember when I was writing about the Atrocity of Shelton Laurel, the massacre of thirteen men and boys by the Confederate troops out there. We ended up not publishing their names in the original, published version of the magazine, because we couldn’t agree what they were. I’m convinced the reason is that there are markers out there at Shelton Laurel that have all the names, and then there are various accounts from people, some contemporaries, some from Congress—because there was a congressional hearing—and the names are all over the place. I think the markers are probably the phonetic versions of what their names were, because these were mostly people who weren’t literate and they said their names with a mountain accent and somebody wrote it down, but they didn’t know if it was spelled right or not because they didn’t know how to read or write. They didn’t need to write anything. If they needed a letter written, they went down to the postmistress and had her write the letter for them. Something as simple as what someone’s actual name was—if you can’t nail that down….

I was re-reading the autobiography of Frederick Douglass the other day, and he was talking about the fact that he didn’t know his own birthdate. They didn’t want slaves to know this; it was one way of denying them personhood and also erasing family ties. They would immediately separate slave children from their mothers on many plantations and have them raised together by one of the older women who could no longer work the fields, and the mothers would be taken off somewhere else. I know this was the practice in many places. When you can’t even identify what your given name was or your date of birth, how do you start to build an identity on that?

Chris Mackowski: I suspect your background as a journalist was a help in researching some of that.

PG: Yeah, it taught me to use multiple sources on everything. The way the book came about from the magazine series was me, long ago, making the decision that I wanted to report the war as if it was happening. I didn’t want to go in with a settled historian’s hindsight. I know a lot of them, even the good ones, that seem very settled on what they know, because they spent their career finding out and they have invested time into their version of it, and I get that. Most of the time they are right, but I also think that there are things that are never going to be settled, like the number of people who died in the war. When I started it, it was 620,000, and by the end it was up around 850,000. The war has been over for 150 years—how can the casualty count keep rising?

And the answer is new statistical methods. They’re looking at different evidence. They are still digging up new graveyards every time they build a new shopping center in Alabama or somewhere. I suspect the true toll is going to be over a million in my lifetime, because of all of the people who were never counted, like the black people for example, all the civilians that died in unmarked graves, the feuds in the mountains, all the soldiers that went missing, all the soldiers that died of wounds a year after the war was over that were still suffering from whatever fevers and ailments they had.

But reporting the war means you go into it with no preconceptions and take it skeptically and try to get to the actuality at the center of events and break through all the noise around it to get to something that feels reliable. When you see a diary entry by a young soldier the night before a battle, that’s probably a pretty good idea of what he was feeling, because he isn’t expecting to publish that. He isn’t even writing it as a letter, just putting it into a private diary. If he’s writing a letter home, it’s going to be reliable, but he’s not going to tell his sweetheart everything—although towards the end of the war, people got surprisingly candid about things, like the fact that they were going to lose, the fact that they were going to die, and the same from the other side.

If you want to find private letters from people who are dead, that’s very hard to do unless you have someone give them to you. But if it was written to someone public and it was preserved…. Governor Vance was the most popular governor in the history of the fucking world. All these people wrote to him like they knew him personally, and he was a good storyteller and all that, but women would pour their hearts out to him, so there is a treasure trove of these letters up in Raleigh that I went through, and his replies to them. He answered all of his mail—he didn’t have secretaries do it—so you get a pretty reliable back and forth, and that’s kind of a god-send.

And then the other advantage of doing the magazine thing is kind of analogous to working for a newspaper: once you publish your piece, people will call you and say, “Hey you included this but you didn’t include that. Do you want some information about that?” And they would send me photostats of letters and diaries and family genealogies that they had compiled. And photographs. One woman had a receipt her great-great-great grandmother had gotten from General Sherman for two mules he took from her barn while he was marching through Goldsboro, or wherever. You start accumulating and almost crowdsource it, and people start sending you things that you could’ve never gotten otherwise.

CM: How much of that sort of material ended up in this version of the book?

PG: A lot of it. All of the stuff about William Henry Asbury Speer. The stuff about the family where all of the cousins and brothers went to war together. Stuff about railroads. Sometimes it was just a little detail here or there, but sometimes it was the whole story. I had contacted the Sisters of Mercy and they were wonderful. Their archivist sent me all sorts of stuff, and they were happy to have that recognized.

CM: I had the same thing happen to me when Kris White and I published our book about the Second Battle of Fredericksburg and Salem Church. As soon as the book showed up in print, we got all these different accounts from people. We were like, “Oh where was this six months ago?”

PG: We’ve been trying to work with the North Carolina Civil War and Reconstruction History Center, trying in a very concerted way for several years to get people to come forward with their stories, especially if they have documents that can be digitized and saved, because the generation that valued that is dying off. There are a lot of people coming up and all they see is a shoebox full of old letters and think that’s just recycling or something.

CM: I wish the technology that exists today existed in 1990. With Ken Burns’ film, interest spiked, but we didn’t have the technology that allows us to capture the public interest that we do now.

PG: Now when anyone shows me anything, I forward it up to Michael Hill at the Archives. Failing that, I take a picture and scan it in myself or have them do it—usually they have a nephew or a cousin or something that can scan it or turn it into a PDF—and I’ll get it by e-mail that way. But some of them can’t—they still have a rotary phone on party line!

CM: I have a colleague who has his wife do all the tech stuff for him because he just hasn’t been able to wrap his head around it.

PG: We had John Updike at UNC-Wilmington several years ago, right before he died. To make the arrangements, we had to hand-write letters to him, and he wrote letters to us with the US mail the whole way, not even a telephone. That’s old school!

————

Tomorrow, as we continue our conversation with author Philip Gerard, we’ll discuss his writing process a little bit. “I always wanted to capture the sense that nobody knows how this is going to turn out,” he says.

1 Response to A Conversation with Philip Gerard on The Last Battleground (part two)