Yellow Fever and Reconciliation

Among the historical memories that still haunt New Orleans are those of the yellow fever outbreaks of the 1800s. As a descendant of Irishmen, who suffered disproportionately from the disease, I heard my grandmother speak of the last few outbreaks of the 1800s. She did not witness them, but her parents and grandparents did. The worst epidemics occurred from 1850-1870, when sectional tension was red hot. In those days Northern newspapers paid the outbreaks little mind, and even blamed them on “Southern decadence.”

Among the last great outbreaks was the 1878 epidemic. The disease was still not understood and efforts at quarantine were useless, although the city did clean up the streets which softened the blow compared to the ravages of the 1850s. Unlike past outbreaks, children were particularly hard hit. Near the gates of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 there is a notable tomb dedicated three children who in 1878 quickly died of the disease known as “Yellow Jack,” “Bronze John,” and “The Saffron Scourge.”

The 1878 epidemic spread far up the Mississippi River, particularly Memphis, where mail stopped because postal workers fled. Vicksburg was also hard hit, and even St. Louis reported cases of the ailment. In total, some 20,000 people died. 5,000 of them were in Memphis and around 3,300 were in Mississippi. New Orleans lost over 4,000.

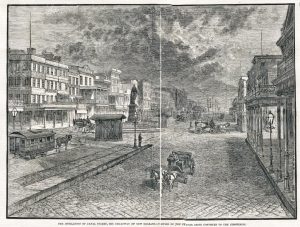

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News Paper covered the 1878 epidemic and provided evocative images. At the same time, reconciliation and social reunification were underway. Charity from the North, which was far more prosperous after the Civil War, came pouring in. In response to Northern generosity, The New Orleans Picayune’s editorial wrote “…we declare that the war is over, now and forever.”

In the aftermath, Judge James Frederick Simmons of Sardis, Mississippi composed a poem titled “The Welded Link.” Published in 1881 with other poems, many of which were about yellow fever, it was a regional success but largely forgotten today, brushed off as Victorian Age schmaltz. Yet, that schmaltz was popular in its day and crucial to understanding the times. The title poem ended with these lines:

“The white flag waves ! Our hearts are conquered now ;

The frown of hate has fled the Southron’s brow ;

Our gratitude, unclaimed, is freely giv’n,

Our vows of love are registered in Heav’n.

And may the brotherhood, oppression-born.

In dear Columbia’s uncertain morn,

And now reborn in her maturer life,

Oblivion fling o’er bitterness and strife, —

Cemented be in one unbroken chain,

To stronger grow and ne’er abrade again;

And may we ever be in deathless love

One brotherhood on earth and one above.”

The 1978 epidemic was followed by a small outbreak in 1879 which claimed only nineteen lives in New Orleans, but among them was John Bell Hood, his wife Anna Marie, and his eldest daughter Lydia. The ten surviving children were cared for by charity, while P.G.T. Beauregard raised money through the Hood Orphan Relief Fund and by publishing Advance and Retreat, Hood’s incomplete memoirs. Although most contributors were Confederate soldiers, several Union veterans organizations sent their share of money. It was another sign that the war’s bitterness was fading.

Yellow fever played an unintended role in reconciliation and reunification. Although the reconciliation narrative has frayed in recent years, it is remarkable that any reunification was accomplished when one compares the American Civil War to that of Russia, Spain, China, and Nigeria to name just a few. Imperfect as it was, America became a united country capable of great achievements. A few veterans saw a united America defeat Germany and Japan in 1945 and the nation emerge as the world’s leading democratic power. By contrast the Soviet Union, Francoist Spain, and the Supreme Military Council of Nigeria no longer exist as governing bodies. The People’s Republic of China still rules the mainland but not Taiwan.

For the North the Civil War was mostly about preserving the union, democracy, and an emerging nationalism. As such, while the South suffered, the devastation was limited compared to other civil conflicts. Most of all, when the people of the South were afflicted by a great epidemic, many in the North responded. By contrast, in Russia Joseph Stalin was busy starving Ukrainians less than twenty years after the communists won the Russian Civil War. That is likely why the eleven states of the Confederacy remain in the American union today while Ukraine became an independent country roughly sixty years after the Holodomor.

Below is James Frederick Simmons’ essay that proceeded “The Welded Link.”

“The original settlers of America, mostly victims of oppression, were drawn and bound together by ties of sympathy, interest, and mutual hardship and exposure. They succeeded in the face of adverse circumstances. The mother-country oppressed them unwisely and unjustly. They resisted, threw off the yoke, and as a band of brothers defied her. War ensued, and the infant republic conquered its independence. The brotherhood continued until evil counsels prevailed, and a bloody fratricidal war was brought on. This, after four years of bloody carnage and unheard-of endurance, terminated in the defeat of the Southern by the Northern arms. Peace was proclaimed, but fraternal feelings did not follow; nor, indeed, had war ended save in active hostilities. The humiliating, bitter sense of defeat burned in the Southern heart, and ruin and desolation prevailed all over the once prosperous Sunny South. In 1878 the yellow fever made its appearance and became epidemic throughout a large portion of the Southwest, entailing death and distress beyond description and too horrible to contemplate. A wail of suffering and sorrow went up from our stricken and unhappy people. It reached the ears and hearts of the North, and elicited such responses as only the noble in soul can make. The men and women came from there to “do or die” for the alleviation of the woe and suffering that held high carnival here, and many of those who came, alas! paid for their devotion with their lives. Besides these, food, clothing, medicines, and all other necessaries, and hundreds of thousands in money were sent for the relief of the sorely stricken and distressed South. Such more than human kindness, charity, and love did what arms never could have done. It conquered the Southern people and the Southern heart. These contributions came, as we were informed, from the hardy laborer and the poor widow, to the extent of their ability, as freely as from the more fortunate and wealthy. God bless them all and unite us with them evermore in one indissoluble bond of brotherhood!”

Thanks for this informative piece. It makes one wonder just what happened to stem the flow of good will.

There is always in every country regional tensions. Even people I know who loudly supported statue removal will also complain about “carpetbaggers” which is really a term for gentrification through Northern transplants.

When do you think the good will ended?

Awhile back I visited the munii in Shreveport and stood where Elvis stood exciting but as I looked across the street at the mound where countless people died from yellow fever I said a lil prayer for the unfortunate souls who perish going and old .. Even doctors and mind who refused to leave.We don’t know how fortunate we are.May the good Lord bless there souls.

That’s young and old and doctors and religious people sorry spell check goof