Rock Star Egos and the Army of Tennessee’s Most Important Inferiority Complex

I’ve been listening this week to the audiobook version of Greg Mertz’s Attack at Daylight and Whip Them: The Battle of Shiloh (one of my jobs, as series editor, is to listen to and approve all the books before they’re released). Historian Timothy B. Smith, in his foreword to the book, pointed out that because of Albert Sidney Johnston’s death during the battle “Confederate command in the West was left for the remainder of the war in a state of turmoil.” Greg’s book sets the table for that larger story by introducing a lot of the key Confederate players.

Of particular interest to me have been the army’s corps commanders.

John C. Breckinridge was a former vice president of the United States and presidential candidate. William Hardee literally wrote the book on infantry tactics, popularly known as Hardee’s Tactics. Leonidas Polk was the Episcopal bishop of Louisiana. Braxton Bragg was…well, Braxton Bragg.

I called my Polish brother, Chris Kolakowski, ECW’s chief historian, and laid this out to him. He’s used to random calls like this from me, when I barely have “hello” out of my mouth before I start bouncing ideas off him.

“Of course, all these guys have egos—that’s kind of the story of the command structure of the Army of Tennessee—but it seems like these guys in particular have rock star-sized egos,” I said of Breckinridge, Hardee, and Polk. They all had accomplishments not just of note but of real significance.

“Polk’s a special case,” Chris noted. “He’s always a special case.” While being bishop of the diocese of Louisiana might not sound to modern readers like a big deal, it’s worth noting that New Orleans was the largest city in the Confederacy. Polk’s position gave him a noteworthiness that he parlayed into actual celebrity. “He laid the cornerstone of the University of the South as recently as 1860,” Chris said. “His name was all over the South because of similar dedications he was involved with.”

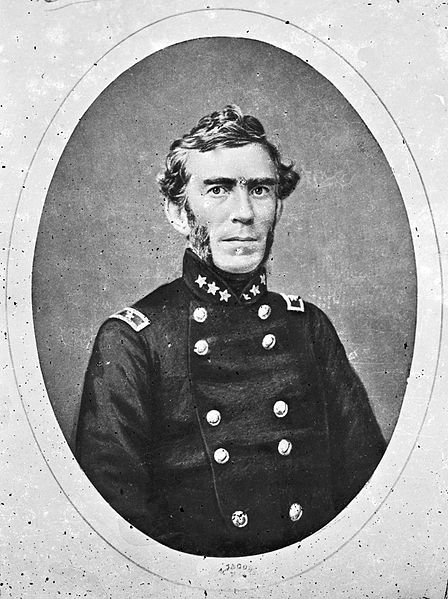

And let’s consider, just for a moment, Albert Sidney Johnston and P. G. T. Beauregard. Johnston had been the South’s most famous military figure at the start of the war, and subsequently Confederate President Jefferson Davis gave him the most difficult assignment: defense of the vast Confederate west between the Allegheny Mountains and the Mississippi River. Johnston certainly had his ups and downs—mostly downs—during his tenure, but despite his setbacks, Davis stuck by him unconditionally. “If [Johnston] is not a general,” Davis told detractors, “we had better give up the war, for we have no general.”

Think about that for a second: If Johnston isn’t a general, we don’t have one.

That’s a bold declaration of faith. Whether he would have ever lived up to that, we’ll never know, but that’s a post for a different day. I’m interested in Johnston’s position in that particular historical moment: Jefferson Davis saw Johnston as the premier general of the South.

Beauregard did not enjoy the same level of support from Davis. But as the Confederacy’s first national hero—first for his successful bombardment of Ft. Sumter in April of 1861, then his victory at First Manassas in July of that year—he enjoyed broad public adulation.

Now into this mix—two men of significant military stature above him and three “rock-star” peers—let’s consider Braxton Bragg.

“He had Buena Vista,” Chris Kolakowski said, referencing the battle from the Mexican-American War. “Of the heroes to come out of Zachary Taylors army, Bragg is one of the most prominent, maybe the most.” The Chris pauses. “But, that was 1847.”

“So, there’s a ‘what have you done for me lately’ factor at play,” I suggest. “He was a war hero—but a lot of guys we know of today were war heroes. And it was a while ago.”

I posit my theory about the extraordinary level of achievement enjoyed by Bragg’s peers. Chris adds more to the mix to think about. “Bragg’s older brother was the Confederate attorney general and later governor of North Carolina,” Chris said. “And there were rumors that Bragg was born while his mother was in jail.” Because of those rumors, people picked on Bragg as a child.

“So he always had an inferiority complex,” Chris said.

The other thing he had—again, dating back to his service at Buena Vista—was the support of Jefferson Davis. Bragg’s artillery fought in support of Davis’s infantry, a connection Davis forever after honored.

But Davis was friends with Polk, too. And Breckinridge would have so much influence he would eventually become the Confederate Secretary of War. So friendship alone wasn’t enough to save Bragg, even if it did sustain him far longer than it should have.

Bragg performed reasonably well at Shiloh (but not without fault). Importantly, it perhaps looked like the old hero of the Mexican-American War might be prepared to replicate his heroics.

With Johnston dead and Beauregard in command but in questionable health, Bragg also had seniority, which made him the ersatz “first among peers” despite the rock-star reputations of the other corps commanders. When Beauregard took a convenient absence without leave in June 1862, citing health problems, Bragg ascended to command over corps commanders who all felt themselves to be his better.

Bragg’s promotion might just as well have come with a sign that said, “Kick me.” The angling that went on behind the scenes between him, Davis, and Beauregard cast a shadow of controversy over Bragg’s ascension from day one, and it foreshadowed things to come. Jealousies, petitions, investigations, cabals, and reassignments—controversies, controversies, controversies—would embroil the Army of Tennessee’s leadership for the next twenty-one months. His harsh disciplinarianism would likewise make him deeply unpopular with his men and, through their letters and through press reports, on the homefront. The grief wouldn’t end until Davis finally promoted Bragg to a desk job in Richmond in February 1864.

In his 2016 biography of Bragg, Earl Hess credibly called him “The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy.” (I highly recommend Hess’s book, by the way.) I think of that title now in the context of my Shiloh musings. If we consider the most notable achievements of the four Confederate corps commanders—vice president, tactical authority, Episcopal bishop, “most hated”—Bragg achieved a superlative every bit as memorable as his peers, although his ultimate claim was to infamy, not fame.

With my limited knowledge, I tend to agree with the above assessment: ego, friendships, personality (and personality clashes) tended to dictate pecking order among military leaders, North and South. Focusing on the South, I offer to add the following… PGT Beauregard got into a squabble via the newspapers with President Davis after Rebel Victory at Bull Run, implying that Davis was responsible for “lack of pursuit of the enemy to Washington.” Eventually cowed by President Davis, General Beauregard requested posting to New Orleans for that valuable city’s defense (and to get away from Davis.) When that request was denied, Beauregard subjected himself to throat surgery (akin to scraping of the tonsils) and was left so debilitated that he was unfit for duty until August 1862. But, when the offer of service under A.S. Johnston arrived, Beauregard leapt at the opportunity, and did his best as Johnston’s subordinate (but should have leapt onto the first available Surgeon for a Sick Certificate, instead.)

Joseph E. Johnston had an enormous chip on his shoulder from Day One, believing he was slighted as regard overall seniority (which was promised to be in accordance with Federal rank, but Johnston discovered his Brigadier General rank was not sufficiently impressive; and he seethed when Samuel Cooper was awarded seniority of Number One.

Polk filled a void until the arrival of A.S. Johnston from California. And then he intended to retire from the Rebel Army and return to his pulpit (submitted at least two letters of resignation.) Unfortunately, while waiting for Johnston, Polk was responsible for jumping the gun and moving Rebel forces into neutral Kentucky, which angered many Kentuckians into throwing their support to the North. Polk was responsible for building an impregnable Gibraltar at Columbus Kentucky, blocking Federal use of the Mississippi River, and which was never challenged. As one of Beauregard’s assignments (initially to replace Polk at Fort Columbus) an unwell General Beauregard sent an aid to inspect Polk’s Gibraltar (after the loss of Fort Donelson and Nashville) and upon the aid’s report, ordered Fort Columbus evacuated. Polk and his 14,000 men then joined the army forming at Corinth (with some going to Island No.10).

Braxton Bragg was upset when Louisiana awarded supreme rank to Beauregard at the beginning of the Secession Crisis and welcomed the opportunity to take command of Rebel forces gathered at Pensacola and Mobile. Bragg, from his letters, appears to have dreamed of establishing a true Camp of Instruction at Pensacola, training men rapidly and thoroughly as possible, and replacing trained soldiers one-for-one with new recruits. Bragg deflected requests to send troops from the Gulf north in keeping with this training goal, and eventually amassed an Army of Pensacola 18,000 strong. But the Camp of Instruction idea failed in practice because too many trained soldiers were held on the coast, while recruits were sent directly into the fight, further north. Bragg was ordered by the Secretary of War to close down his Pensacola operation and take his extremely well trained force to Corinth.

Albert Sidney Johnston. Did the best he could with the forces available. (His method of interacting with subordinates and empowering them is still taught in the U.S. Military.) We will never know “what might have been.”

Thanks for this really insightful post (and I concur regarding the Hess book). A few minor points. (1) Polk graduated West Point but then had about 15 minutes of military experience before the Civil War; (2) Bragg was essentially a battery (artillery company at the time) commander in the Mexican War, eventually taking command of Ringgold’s Battery C 3rd US after the latter was mortally wounded at Palo Alto; (3) we can debate at another time whether Johnston’s death changed the fortunes of the Army of Tennessee. Aside from his bizarre tactical and command arrangements at Shiloh, he would have been dealing with the same dysfunctional crowd of subordinates. adding Bragg to that mix and fueled by Davis’s meddling and favoritism. .

I liked Hess’s book as well and I also like the fact that he gave Bragg a fair shake; the truth about Bragg has to lie somewhere between all the bad press and the actual ability he displayed (or conversely, didn’t). And speaking of the press, Hess also pointed out how singularly ill-equipped Bragg was in dealing with the media of the day, which also helped blacken his reputation.

Lee that is an excellent analysis. Exactly what I would expect from you. I’ve convinced Greg to do a Shiloh tour in 2021. Look forward to yours in Tennessee in December.

One thing to keep in mind regarding Kentucky – actually two. First, the Federals violated its neutrality first with the opening of Camp Dick Robinson in August 1861 – a month before Polk moved into western Kentucky. Then we have the issue of the “Lincoln Guns” being sent into the state to equip pro-Union forces, which, prior to Dick Robinson, actually went to camps in southern Indiana and Ohio – as the pro-Confederates did with Camps Boone and Burnett near Clarksville, TN. Even before this, however, we have instances on Union gunboats entering the Paducah Harbor and Cumberland River to seize boats with war material on them – both violations of Kentucky as they owned (and still do) the Ohio River to within the shores of Ohio, Indiana and Illinois. Benjamin Prentiss, when we has in charge of Cairo (pre-Grant), sent boats of armed men into the Ohio River to check the manifests of steamboats in case they carried Confederate war materiel. The Southerners called them “Prentiss’ Buzzards.” KY Governor Beriah Magoffin had assurances from Lincoln that he would not violate the state at the time (although if you read the ending of his note it was VERY open ended) and then when Magoffin protested Camp Dick Robinson, Lincoln wrote back wondering why he was upset that Kentucky men would form into units to protect their state – and conveniently leave out news about the 1st and 2nd Tennessee Infantry (US) that were also forming there. The Federals were after Columbus too, On August 28th, a Union regiment landed at Belmont, MO. and were told to go after Columbus if practicable by John Fremont, who commanded the Department of Missouri before Halleck.

Secondly, most of what Kentucky produced economically went north across the Ohio River. People tend to follow the money and Kentuckians certainly did just that. The only thing that would have tilted them into the Confederate sphere was if Bragg had crushed Buell and then keep the Army of the Mississippi in the commonwealth for protection. Still, as Larry Daniel notes in his new book on the Army of Tennessee, some 70 per cent of Kentucky military age men sat out the war completely! That is a staggering manpower loss for either side.