Gen. Jackson and Mr. Hyde: Which Account of Stonewall Jackson at Harpers Ferry is the Correct One?

On the morning of September 15, 1862, Stonewall Jackson had just completed a profound military achievement. Three separate columns all nominally under his command converged on a single point–Harpers Ferry–nearly simultaneously. They ensnared the Federal garrison positioned around the town and forced its surrender. Roughly 12,500 Union soldiers surrendered and were removed from the war map in the summer of 1862 all at the cost of just 39 Confederate lives.

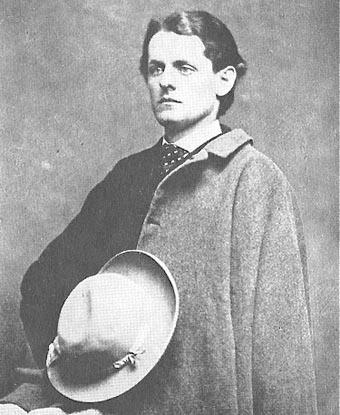

It is in this supreme moment, as the victorious Jackson rode toward Union lines to accept the largest surrender of United States forces in American history at the time that the humble, quiet, backcountry born Jackson failed to fit the scene. In all his glory, Jackson appeared as “the worst-dressed, worst mounted, most faded and dingy-looking general” anyone had ever surrendered to. At least, that was how one of Jackson’s staffers, Henry Kyd Douglas, remembered the scene.

In the eternal war of opinions and facts fought (and still being fought) over Jackson’s legacy, two of the general’s other staff officers, Jedediah Hotchkiss and Hunter McGuire, vehemently denied Douglas’ account. In fact, they denied almost all of them. Hotchkiss wrote of Douglas’ recollections of the war, “He shoots with a long bow and generally misses the mark.” When it came to Jackson’s appearance at the time of the Federal surrender on September 15, Hotchkiss, buttressed by a similar statement from McGuire, claimed, “Jackson was always neat in his person and his faded old grey cap had been replaced by a handsome soft slouch hat that I had bought him in Frederick and his uniform was neat and well fitted but of course more or less dust stained and therefore looking faded. He was always neat in his person. I think that at that time he also had on the handsome blue military coat that he always had with him as the morning was decidedly cool.”

Here comes the rub for historians. Who is right? Douglas or Hotchkiss and McGuire? Both wrote their accounts decades after the war. Both refuted the other with different details of the same story. In short, it is a judgment call for historians.

In the end, the details of the story do not detract from the larger picture. Jackson freed the Shenandoah Valley of Federal forces at a crucial time in the Maryland Campaign. Did he do so as a “dingy-looking” commander or as one “always neat in his person”?

I’m more inclined to believe a mix of the two. Jackson did cut a sometimes comical figure with his faded cadet cap pulled low over his brow, dingy coat, and rode a horse that was too short for him. It wasn’t until before the battle of Fredericksburg that he received a better outfit as a gift from JEB Stuart. I think what comes into play here is a difference of reverence for Jackson’s memory. I don’t fully know the general opinion of Jackson from Hotchkiss and Douglas, but “Stonewall” seems to get immortalized as a great military commander who died early in the war and – for lack of a better way to put it – became somewhat canonized after the war as this wonderful Confederate saint. No one would DARE say something bad about Jackson because it would tarnish his posthumous reputation. Just consider how Longstreet’s outspokenness about Lee screwed him over in the history books for a long while. I prefer the image of Jackson not looking his best because it would have been like the twisting knife to the surrendered Federals to see that they had been captured by someone who didn’t come with polished brass, all neat and pressed, riding a great white horse type. Instead, they met the famous Stonewall Jackson.

I have always had the impression that ol’ Stonewall never left anyone ‘neutral’ in their evaluations and/or recollections of him. They either loved him or hated him. Period. Some subordinates viewed him as flat-out crazy. His penchant for not communicating his thoughts to subordinates contributed to that. His own immediate staff offers such conflicting reports on him here. He continues to be as ‘odd of a duck’ as there ever was.