Mrs. Gordon Rallies The Troops In Winchester?

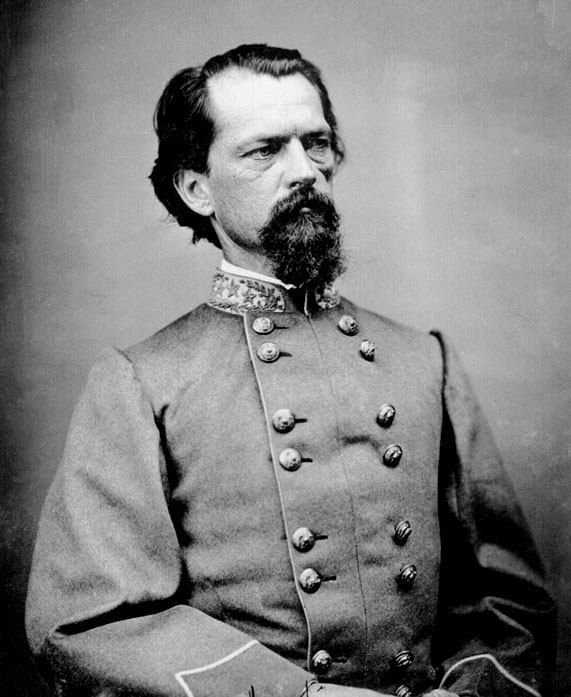

General John B. Gordon had much on his mind on September 19, 1864. The Yankees fought tenaciously, driving back his troops. His friend, General Rodes, had been carried off the battlefield mortally wounded, and Gordon blamed himself for not having time to say goodbye. Meanwhile, General Breckinridge continued to ride into danger, and when Gordon warned him, the former vice-president responded: “Well, general, there is little left for me if our cause is to fail.”

At this point, with his soldiers fleeing the hard fought battle outside Winchester, that General Gordon also retreated, passing through the streets of the embattled town. Then, he found a scene that disturbed and amazed him:

To my horror, as I rode among my disorganized troops through Winchester I found Mrs. Gordon on the street, where shells from Sheridan’s batteries were falling and Minié balls flying around her. She was apparently unconscious of the danger.

Mrs. Fanny Gordon had a reputation in the Army of Northern Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley. One general had remarked: “If my men would keep up as she does, I ‘d never issue another order against straggling.” She went on nearly every campaign, keeping up with the army in a carriage. She had helped to save her husband’s life at the Battle of Antietam in 1862.

While most officers accepted Mrs. Gordon’s adventuring without recorded comment, General Jubal A. Early, commander of the Confederate Army of the Valley in autumn 1864, had some remarks. A cantankerous bachelor, Early once exclaimed, “I wish the Yankees would capture Mrs. Gordon and hold her till the war is over!” News of that statement reached Mrs. Gordon and during a camp dinner hosted for the officers, she teasingly called him out about his words.

He was momentarily embarrassed, but rose to the occasion and replied: “Mrs. Gordon, General Gordon is a better soldier when you are close by him than when you are away, and so hereafter, when I issue orders that officers’ wives must go to the rear, you may know that you are excepted.” This gallant reply called forth a round of applause from the officers at table.

On September 19, 1864, Mrs. Gordon had already had a narrow escape from spending time as a Yankee prisoner. According to John B. Gordon’s post-war reminiscences:

As the fighting was near Winchester, through which Mrs. Gordon was compelled to pass in going to the rear, she drove rapidly down the pike in that direction. Her light conveyance was drawn by two horses driven by a faithful negro boy, who was as anxious to escape capture as she. As she overtook the troops of General Rodes’s division, marching to the aid of Ramseur, and drove into their midst, a cloud of dust loomed up in the rear, and a wild clatter of hoofs announced, “Cavalry in pursuit!” General Rodes halted a body of his men, and threw them in line across the pike, just behind Mrs. Gordon’s carriage, as she hurried on, urged by the solicitude of the “boys in gray” around her. In crossing a wide stream, which they were compelled to ford, the tongue of the carriage broke loose from the axle. The horses went on, but Mrs. Gordon, the driver, and carriage were left in the middle of the stream. She barely escaped; for the detachment of Union cavalry were still in pursuit as a number of Confederate soldiers rushed into the stream, dragged the carriage out, and by some temporary makeshift attached the tongue and started her again on her flight.

When Mrs. Gordon reached temporary safety in Winchester, she did not continue her journey up the Valley. Instead, she stopped at her friend’s home. Mary Greenhow Lee lived at 133 North Market (Cameron) Street, and Mrs. Gordon had spent some time with her in the past weeks. Perhaps she thought the battle would end in a Confederate victory. Perhaps she was tired or feeling emotionally rattled after her battlefield escape. She was in the early months of pregnancy at the time and perhaps needed to rest.

Interestingly, Mary Greenhow Lee did not record Mrs. Gordon’s sudden arrival or any details about her near capture. She recorded the battle hours this way: “All the time couriers & friends were passing our house being in the immediate line of communication. We heard every hour or so of Genl. Gordon’s safety; ambulances were continually passing with the wounded.” When General Rodes arrived in one of those medical conveyances, “Mrs. Gordon and I ran up to the Hospital to see him & I intended having him brought to our house, but I found he was dead.”

Around noon, the ladies heard soldier rumors about “falling back,” and following their mid-day meal, they saw cavalry and infantry hurrying in confusion past the house. They determined to do something. “We stood on the porch & pavement & shamed them & by dint of reproaches & encouragement succeeded in turning them back.” About that time, some men from Mrs. Lee’s acquaintance showed up wounded and occupied her attention.

According to General Gordon, when he retreated into town, he found his wife in the street while artillery shells whistled through the air; he detailed his wife’s actions:

…As the first Confederates began to pass to the rear, she stood upon the veranda, appealing to them to return to the front. Many yielded to her entreaties and turned back– one waggish fellow shouting aloud to his comrades: “Come, boys, let ‘s go back. We might not obey the general, but we can’t resist Mrs. Gordon.” The fact is, it was the first time in all her army experience that she had ever seen the Confederate lines broken. As the different squads passed, she inquired to what command they belonged. When, finally, to her question the answer came, “We are Gordon’s men,” she lost her self-control, and rushed into the street, urging them to go back and meet the enemy. She was thus engaged when I found her. I insisted that she go immediately into the house, where she would be at least partially protected. She obeyed; but she did not for a moment accept my statement that there was nothing left for her except capture by Sheridan’s army.

Mrs. Gordon continued to delay her departure. According to Mary Lee, at the same time she had been looking after her wounded friends:

“There was a great hurry about getting Mrs. Gordon off. Hugh Haralson had gone off with one of her horses & there was not another one to had. While still waiting & while Gordon’s Division was running by, Genl. Gordon & staff dashed by our door. He spoke a few words to Mrs. Gordon, then seized a flag & called to the running soldiers to rally & follow him. We shouted & cheered & called to the soldiers to rally and follow their leader, but to little purpose. At last horses were found & Mrs. Gordon hurried off, shells flying around all the time.”

There seems to be only some slight discrepancies in the two accounts. General Gordon offers a dramatic view while Mary Lee wrote more subdued version of the event. Laura Lee—Mary’s niece—recorded it even more briefly: “Mrs. Gordon and Mrs. Breckinridge, who arrived only last night, got off among the last, while the shells were whistling over the town every moment and the Yankee skirmishing drawing very near.”

Comparing both accounts, suggests that both tell the same story, albeit Gordon’s narrative rings with more drama. The ladies had been on the porch and by the street, haranguing the soldiers to turn and fight. Mrs. Lee’s account and distraction with her wounded friends certainly offered a moment when Mrs. Gordon could have stood alone and then rushed into the street just prior to the general’s arrival.

A couple points to consider emerge in these accounts. First, women were invested in the Civil War, especially emotionally. The breaking of the Confederate army at Third Winchester prompted a general’s wife and prominent civilian to the side of the street to shout at the soldiers. They could not bear the idea of defeat, and while these ladies would not actually fight on a battlefield, they determined to attempt to rally the troops running through town. Second, although General Gordon saw nothing wrong with the idea of female family members accompanying their soldiers on a campaign, this incident points out the dangers of that idea. Mrs. Gordon narrowly escaped capture twice within twenty-four hours and, on this day, did not exhibit the clearest judgement for when she needed to leave.

Since the majority of women were not with armies during the Civil War, especially during military campaigns and active battle scenes, the account of Mrs. Gordon attempting to rally the troops in Winchester offers a remarkable and active glimpse into the emotions and reactions of Southern women to Confederate defeat. Many did not sit passively on the side lines of the war, though most did not run into a battle street. They took other approaches, including emotionally-driven responses—refusal to take allegiance oaths, refusal to obey Federal provost marshals, and later a continued war for how their cause and soldiers would be remembered.

Sources:

Gordon, John B. Reminiscences of the Civil War (Electronic Edition) Accessed at: https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/gordon/gordon.html (Pages 318-323)

Lee, Laura and Julia Chase, edited by Michael G. Mahon. Winchester Divided: The Civil War Diaries of Julia Chase and Laura Lee. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. Page 168.

Lee, M.G. edited by Eloise C. Strader. The Civil War Journal of Mary Greenhow Lee. Winchester, VA: Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society. Pages 414-416.

It is astounding to me how many Confederate women refused to acknowledge that their cause was actually lost. In almost any other country their actions would have resulted in dire consequences. And yet …

In September 1864 many people in the South did not consider the Confederacy to be doomed to fail. The national elections had not yet been held and hope, though waning, was still alive in many hearts. Behind U.S. lines there were dire consequences for expressions of support for the Confederate cause. These consequences are documented in the “Provost Marshal Records of the United States Army”, available in the National Archives.

Good point, Michael. However, I’ve been looking at this regionally, and Third Winchester and Fisher’s Hill definitely started to break Confederate morale in the Shenandoah Valley or at least transform it to a more despairing or bitter tone.

Entertaining ancecdote.