A Conversation with Carol Reardon (part two)

(part two in a series)

(part two in a series)

I’m talking this week with Carol Reardon, whom I like to call the “grand dame” of Civil War history. As she explained in yesterday’s segment, her road to Civil War studies started in the field of biology and took some unexpected twists and turns, even taking her, eventually, to the study of the Vietnam War.

Chris Mackowski: I mean, it makes perfect sense. If you think about the echoes from the Civil War onward and how, through the Civil War, you can see traces of the wars that came before it. How has that broader view of military history helped you better understand that narrower subject. So tie that study of Vietnam to the Civil War for me.

Carol Reardon: I hope it made me a better historian. Here’s why I say that.

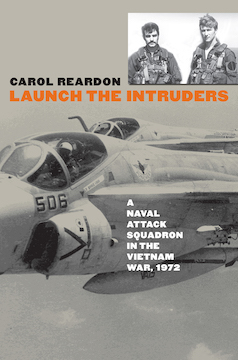

All of us who focus on one field, like when we do our Civil War work, once we get to the fourth and fifth book or whatever, there are elements of our work that almost become formulaic. We know we’re going to look at the newspapers. We know we’re going to look at the O.R. We know we’re going to do some work in diaries and letters and other primary sources. What I found particularly challenging and exciting about the Vietnam project [her book Launch the Intruders (Univ. Press of Kansas, 2005)] was that it had a different source base. I was still reading diaries and letters because, amazingly, I found some, and there were still some newspapers, but the rest was all so foreign to me.

For example, there’s a whole new technology to learn about. And thinking about aviation, or warfare in the air, and three-dimensional operations as opposed to just being on solid ground. Things like that. There were plenty of times that I had to go back to the basic foundations of the methodology that underpins what we do. All those things that you feel very confident about when you’re doing Civil War work—now you have more questions when you’re using it in a very different context, when talking about Vietnam.

It also makes you revisit questions about bias. It makes you revisit concerns about when you have two sources that tell you different things about one specific event. Which way do you go? It can alert you to pitfalls that you wouldn’t see coming in the Civil War world, and it just reminds you to be a lot more careful with the source material.

I was learning how to read the maps that the aviators used in mission planning, learning how to take the coordinates out of their log books and put them on the map to figure out where their different missions were flown. That was one new skill I had to master. In a completely different part of the project, I also asked all the aviators I was writing about to tell me about their first combat mission. I relied upon some of my memory-studies background from the Civil War where a lot of times—especially when it was a first-time experience, like the first time you went into battle—the memories usually remained a little more vivid because you’ve never done it before. So, I figured, okay, the first time you strap in for a combat mission, that’s probably going to cause an adrenaline rush and things are going to be a lot more vivid in your memory. So, I asked the questions, and I started getting back these tremendous answers. At one point I thought, “This is going to be the easiest chapter to write in the whole book.”

But, I was still trying to learn how to read these maps, and that led me to a puzzle. I was talking to one of the aviators, and he told me he had flown his first mission slightly northwest of Saigon. So I figured out roughly where that was on the map. But I’m looking at his log book and following the coordinates, they put his target well south of Saigon. They weren’t even really close. What was in his log book does not fit the story that he told me. So, I’m trying to figure out what the problem was. I put the map in front of him, and I said, “I’m going to read you these coordinates. Show me where on the map it is.” And I read the coordinates, and he pointed to the location south of Saigon. But he had told me a story about a first mission that was northwest of Saigon, so I’m still trying to figure out what was going on.

Well, we finally did work it out, and it dawned on me what had happened. What they were remembering was not necessarily the first combat mission, but the first combat mission where they took fire. The first couple of missions were mostly reconnaissance and they didn’t run into any hostile fire, so their memories of those first sorties just sort of blended into all the unexciting ones, and they forgot the details of it. What they were remembering was the first time they took fire, because that’s what really pumped the adrenaline up. What he had remembered was his third mission where he got shot at for the first time—and I had the coordinates to prove that that’s where he was.

But it was really interesting to sit back with him and say, “Remember what you told me about your first mission?”

“Oh, yeah,” and he goes off and explained it again.

I said, “That wasn’t your first mission.”

“Yes it was; I’m sure it was.”

“No, no it wasn’t. I can prove it by the coordinates.”

“No, I’m absolutely sure. You’re wrong, you’re wrong. And you’re putting it all on me.”

But I had the evidence and I could lay it down, and the conversation usually ended with something like, “Well, I guess I’ll have to read the book to find out what I did.”

I didn’t take my narrative anywhere that the evidence didn’t take me. And once they saw how I laid it out there, they usually admitted, “Yeah, well, I can’t contradict you on that.” And then they’d back down and they grew to appreciate the historical method a little bit more.

It was little things like that, which in the grand scheme of things probably didn’t matter a whole lot, that made me so much more alert to methodology because I was now on turf where I didn’t feel quite as confident in my knowledge of all the minute details. I think it made me a better historian.

Chris: When you’ve got source material that you can actually interact with as you can in a conversation, that’s a lot different than reading someone’s memoir that was written 40 years after the fact, or reading the O.R. or whatever. That’s a whole different type of experience.

Carol: It really is. It was the first time that my source material could argue with me.

It was interesting afterwards—after the book was out—I asked them if there was anything they purposely did not tell me. I know they never sat down as a group and decided, “Well, we’re not going to tell her about this or that,” but I got to know some of these guys pretty well, and afterwards, if I met up with them and we started talking about this, I’d say, “Okay, time to come clean. Is there anything you didn’t tell me?” Some of them said, “No, you said you wanted it all, and if you asked, I answered your questions. Now, if you didn’t ask, I didn’t necessarily tell you, but any question you asked me, I answered.”

But a couple of them agreed on one thing that each of them as individuals had chosen not to tell me. There was an incident where the commanding officer was killed in a launch accident. His plane had been in for maintenance and a piece of equipment was not screwed back into place securely. When the plane launched off the catapult, this piece of equipment came loose and pinned his hand with the control stick up against his chest. He couldn’t control the plane. It went up in the air, stalled, and went down into the Gulf of Tonkin.

Chris: Oh, gee.

Carol: The squadron was on stand-down and the mission popped up quite unexpectedly. When they first brought the plane up from below deck, they apparently did not have time to do all the safety checks they would have done in a normal situation. As the plane was on the catapult, one of the young aviation technicians came running up with the bolts in his hands, trying to say, “Stop the launch! Stop the launch!” And, of course, he couldn’t do it, and the plane went off, and there he is, still holding the bolts.

The guys, my aviators, they knew the young man. They knew his name. And they all purposely did not tell me who it was.

The odd thing is I found out who it was. I already knew, but I had already made the decision that I was not going to use the name, either. There was not a need to do that. I figured that person has had to live with it for all those years. You know, I never met the man, and I don’t know how it affected his life. But I decided I would not be the one to re-open an old wound if that’s what it came down to.

But that was the one thing a few of them admitted that they knew but did not tell me.

So, dealing with source materials that can talk back yo you is pretty interesting. I asked them if I got anything wrong. The response was interesting—there were a few bits and pieces that they quibbled with. I’m not sure if I was wrong or not. It might have been a memory thing. There were a couple of my interpretations that they took issue with, mostly because they were assessments I had to make of individuals who were still alive at the time I wrote, and they thought that I might have been a little excessively harsh on one of them in particular. That was something I had been aware of as I was writing, but those were the segments where I most heavily relied upon the evidence so that it really wasn’t me making the negative assessment; this is what your squadron mate said. Period. They understood I had good source material for it. They just thought I could have been nicer.

————

Carol’s story about withholding the name of the aviation technician touches on an often-overlooked component of a historian’s work: the role of ethics. We’ll explore that in greater detail in tomorrow’s segment of the conversation.

Good on Carol for withholding the mechanics name. I think it the right thing to do. It certainly mustn’t have been malicious and if the guy is still alive why dig up that pain and regret I’m sure he’s had to deal with his whole life since. He made a terrible mistake, but it was a mistake, and he was there honorably serving his country. I think that warrants discretion, at least while he’s still alive. Definitely not a type of problem Civil War scholars encounter, and I think they should be thankful for it.

But undoubtably there are unreported negligent matters that had larger adverse effects in Civil War engagements we will never know, which i would think should make us slow to judge, and perhaps extend some grace.