Ending the War: James Tanner and his Cherished Memories of the Awful Night

James Tanner had never seen Tenth Street so full of people. The crowd packed the street in front of his second-floor apartment. Tanner sat on his porch, looking down into the mass of people. Dignitaries and generals came and went, and the crowd size continued to increase. However, they were “very quiet” but “very much excited.”

Like everyone else in Washington on April 14, 1865, Tanner was wrapped in joy over the surrender of Robert E. Lee and his Confederate army five days earlier. Washington City was one constant party. It seemed that four years of killing and maiming were nearing an end. Unfortunately, one more trigger was pulled and one more man, at the height of his fame, was shot. The quiet crowd Tanner overlooked huddled together on Tenth Street to receive news, confirm fears, and as if their presence alone might save him, pray for the life of Abraham Lincoln, recently wounded by an assassin’s bullet and lying in the Petersen House adjacent to Tanner’s building.

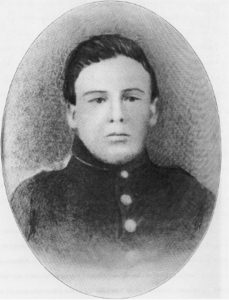

Though fresh off his twenty-first birthday, the horrors of the last four years in America were not new to Tanner. Like most other boys at such a young age in 1861, Tanner yearned to join the army and preserve the divided Union. At the Battle of Second Manassas, as Tanner lounged on the ground, legs crossed at the ankles, an enemy artillery shell exploded above him. One piece of shrapnel hit Tanner’s legs near his ankles, mangling both limbs. Tanner’s feet remained attached to his legs but just barely.

Nearby soldiers rushed Tanner to a hospital, where a surgeon removed both of his feet. Tanner survived this ordeal. Only eighteen years old, he was crippled for life. Tanner easily could have claimed that he did his part to save his country and returned home to live the rest of his life in peace. But Tanner refused to sit quietly for his remaining years. He received prosthetic limbs and learned phonography, a form of shorthand.

Tanner assumed several temporary jobs for New York state before moving to Washington in 1864 to work as a clerk for the War Department. His phonography skills were known to his peers though he did not necessarily use them daily.

In the chaos of the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton feverishly worked from the Petersen House parlor to obtain the testimony of eyewitnesses to the President’s wounding (Lincoln silently lay in a bed in an adjacent bedroom, clinging to life). But writing all of this down was a slow process. Someone in the Petersen House suggested Tanner’s phonographic skills would be helpful.

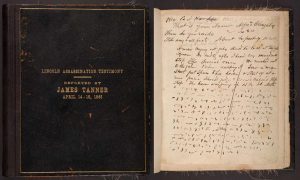

A call went up to Tanner’s balcony. Tanner proceeded downstairs into the jammed street and the Petersen House parlor. Tanner sat near Stanton, who turned the parlor into his temporary office. While the war secretary began the hunt for Lincoln’s assassins, Tanner recorded the fresh eyewitness accounts of what transpired inside Ford’s Theater.

The interviews concluded about 6:45 a.m. Tanner then made his way into the bedroom where Lincoln lay, finding a place to witness the President’s last minutes next to Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs. At 7:22 a.m., Lincoln breathed his last. Aware of his participation in such a historic event, Tanner fumbled in his pockets for a pencil. He found one and began to record the scene. Unfortunately for historians, his pencil tip broke and Tanner had to write his recollections of the scene at a later time.

But Tanner’s task was not yet complete. He hurried back to his room to make a copy of the testimony he recorded in shorthand. After passing his copy to the War Department, Tanner finally took in all he witnessed. “I would not regret the time and money I have spent on Phonography,” he told a friend, “if it never brought me more than it did that night, for that brought me the privilege of standing by the deathbed of the most remarkable man of modern times and one who will live in the annals of his country as long as she continues to have a history.” As for the original testimony Tanner recorded, he kept them. They “will ever be cherished monuments to me of the awful night and the circumstances with which I found myself unexpectedly surrounded, and which will not soon be forgotten.”

For most soldiers, battlefield wounds ended their war experience. For Tanner, his wounds easily could have done the same for him. Ultimately, though, his war ended at the same time as it did for everyone else. But Tanner had a front-row seat to the saddest tragedy at the end of the Civil War.

Simply the finest piece of writing I have read on this blog. Bravo!

Thank you, David. I’m very humbled.

What unit did Tanner serve with Kevin?

He enlisted with the 87th New York but when he was wounded, he was loosely and unofficially attached to the 105th Pennsylvania Infantry. The 87th was in rough shape and was eventually just folded into the ranks of the 40th New York.

“America’s Corporal” by James Marten (2014) is on the way, after reading Wikipedia’s brief on Tanner at the 1912 cornerstone laying of the Confederate Memorial at Arlington Cemetery. I was inspired to look further by your seminal blog. Congratulations on your hard work to find the “most famous person in the 19th century that no one ever heard of”.

That’s an excellent book. I’m glad you were inspired. Tanner’s story is a great one.

THANK YOU Kevin YOUR AN ASSET E.C.W..I HAVE HAD THE HONOR TO STAND IN THAT ROOM .

Thanks for reading, Tom. Standing in the Petersen House is one of the most moving experiences I’ve had at any historic site. Take care and stay safe!