Ending The War: John Wise’s Eulogy

And so I left them. As I rode along in search of the ford to which General Lee had directed me, I felt that I was in the midst of the wreck of that immortal army which, until now, I had believed to be invincible.[i]

And so I left them. As I rode along in search of the ford to which General Lee had directed me, I felt that I was in the midst of the wreck of that immortal army which, until now, I had believed to be invincible.[i]

Part of John Wise’s life ended in April 1865. From his earliest memories, he had believed in the ideals of the South, but coming of age during the Civil War caused him to question and later re-evaluate much of what he had enjoyed and revered in youth. His father—Henry Wise—had been governor of Virginia during John Brown’s Raid in 1859 and that had been the starting moment which fired the boy’s imagination for military service.

When talk of a coming war echoed in Virginia homes in 1860 and early 1861, John Wise saw little harm in a conflict. He summarized his feelings as “Let it come. Who’s afraid?”[ii] When the war actually began, the young teen spent hours spurring his horse at targets in the barnyard and planning to become a cavalryman and knightly lancer. He also played at being an artillery captain, shooting his toy cannon at geese, boatmen, and important ship models.

The fun and games ended abruptly, though, when Wise’s older brother was killed in combat in 1862. A desire to fight and perhaps avenge his beloved sibling continued to fire Wise’s imagination. He made rash comments about running off to join the Confederate army, prompting his father to pack him off to southwest Virginia to work on a remote family farm. But the fifteen-year-old continued speaking with rash enthusiasm, begging his father by letter to let him get in the military…or else!

In September 1862, Wise arrived at Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia—forbidden to enlist, but allowed to enter the state corps of cadets. Drilling, studying, and the occasional march to guard the community from roving Union cavalry occupied Cadet Wise’s days. Some of his fellow classmates studiously worked on racking enough demerits to get kicked out of VMI so they could enlist in the Confederate army.

However, on May 10, 1864, everything changed. Confederate General John C. Breckinridge had called for the corps of cadets to join his gathering army to oppose Union General Franz Sigel’s invasion of the Shenandoah Valley. Five days later on May 15, Cadet Wise found himself detailed with two other cadets to guard the corps’ baggage wagons. That wasn’t good enough. “. . .one thought too possession of me and that was, if I sat on a baggage wagon while the corps of cadets was in its first, perhaps only engagement, I should never be able to look my father in the face again.”[iii] Making a dramatic speech to his cadet companions, Wise persuaded them to leave their assigned posts with him and join the rest of the corps. During the advance down Shirley’s Hill as the VMI Cadets came under fire for the first time, the force of an exploding shell knocked John Wise off his feet and he woke a few hours later with a slight head wound and the combat “experience” he had desired.

Following the Battle of New Market, the VMI Cadets journeyed to Richmond. From there, John Wise got permission to join the Confederate army around Petersburg. Associating with Confederate officers, carrying messages, making trips to Richmond, and indulging in hero-worship. “Until now, I had lived in torturing apprehension lest a perverse fate should deny me opportunity to see them, and to follow, however humbly, leaders who had been the subject of my thoughts by days and dreams by night since the struggle began. Here they were all about me; a house, or a tent by the roadside, decorated with a headquarters flag, guarded by a few couriers, was all that stood between their greatness and the humblest private in the army. They were riding back and forth, and going out and coming in at all hours, so that everybody saw them.”

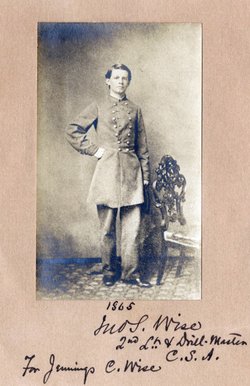

For the next months, Wise relished serving and watching his heroes: Lee, Beauregard, A.P. Hill, Hampton, Mahone, Fitz Lee, Pegram, and others. He commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Confederate army and spent the remaining months of the war carrying messages and making observation.

As the weeks wore on, though, Wise’s dreams of glory faded as he faced the realities of diminishing supplies, the weakened army, and little chance of escape. On a trip to Richmond, he realized, “This is but the beginning of the end.”[iv]

On April 2, 1865, Wise waited at his assigned post at a train station, witnessing the arrival of telegrams from the fighting at Petersburg. He saw Davis and the Confederate cabinet flee from Richmond.

When we recall the way in which the most startling events in our lives have happened, we note how differently they unfolded themselves from our previous thought of them. Nay, more: we all recall that when great events, which we had anticipated as possible or probable, have actually begun to occur, we have failed to recognized them. So it was now with me. That the war might end disastrously to the Confederacy, I had long regarded as a possibility; that our army was sadly depleted and in great want I knew; but that it was literally worn out and killed out and started out, I did not realize. The idea that within a week it would stack arms at Appomattox, surrender, and be disbanded did not enter into my mind even then. I still thought that it would retreat, and, abandoning Richmond, fall back to some new position, where it would fight many other battles before the issue was decided.[v]

Later in that decisive week, Wise carried a message to General Lee, arriving on the evening after the Battle of Sailor’s Creek. Within hours, Lee strategically sent him away again, carrying a message to Jefferson Davis. As he rode south, Wise realized that the Army of Northern Virginia which he had believed was immortal was on the brink of surrender. The leaders he had believed in and worshiped for four years could not secure a victory, and he had to mentally handle that reality. After delivering the message to Davis, Wise joined Johnston’s army and finished his military and war experiences in North Carolina. Then, he returned to Richmond, rejoining his family but without a place to truly call home.

Putting on civilian clothes marked a significant moment for John Wise. “When I looked in the glass, instead of confronting a striking young officer, I beheld a mere insignificant chit of an eighteen-year-old boy. Nothing brought home to me more vividly the fact that the stunning events of the last month had ended the career on which I had started, and that I had received a great setback in manhood. This feeling was emphasized when someone startled me by asking where I was going to school.”[vi]

That night, troubled by the past, present, and future, John reported being unable to rest. In the morning, he got up early, penned a satirical will, and started grappling with the realities of the past four years and the future:

I, J. Reb, being of unsound mind and bitter memory, and aware that I am dead, do make publish, and declare the following to be my political last will and testament.

- I give, devise, and bequeath all my slaves to Harriet Beecher Stowe.

- My rights in the territories I direct shall be assigned and set over, together with the bricabrac known as State Sovereignty, to the Hon. JET, to play with for the remainder of his life, and remainder to his son after his death.

- I direct that all my shares in the venture of secession shall be canceled, provided I am released from my unpaid subscription to the stock of said enterprise.

- My interest in the civil government of the Confederacy I bequeath to any freak museum that may hereafter be established.

- My sword, my veneration for General Robert E. Lee, his subordinate commanders and his peerless soldiers, and my undying love for my old comrades, living and dead, I set apart as the best I have, or shall ever have, to bequeath to my heirs forever.

- And now, being dead, having experienced a death to Confederate ideas and a new birth unto allegiance to the Union, I depart, with a vague but not definite hope of a joyful resurrection, and of a new life, upon lines somewhat different from those of the last eighteen years. I see what has been pulled down very clearly. What is to be built up in its place I know not. It is a mystery; but death is always mysterious. Amen.

Wise’s family laughed when he read this document to them at the breakfast table, hurting his feelings and seeming unaware of his thoughts and struggles. He stood at a crossroads. He faced serious choices whether to hold to the past, run toward bitterness, or forge a new future.

“Everything that I had ever believed in politically was dead. Everybody that I had ever trusted or relied upon politically was dead. My beloved State of Virginia was dismembered. . . Every hope that I had ever indulged was dead. Even the manhood I had attained was dead. I was a boy again, a mere child—precocious, ignorant, conceited, and unformed. I had set my heart and soul on the career of a soldier. What hope was left for that? . . . . In hopelessness, I scanned the wreck, and then—I went back to school.”[vii]

Literally and metaphorically. John Wise visited his uncle, General George Meade, in Philadelphia for the summer. In the autumn, he went to college and joined the baseball team. By 1867, he had graduated from University of Virginia and was admitted to the bar that same year. Two years later, he married Evelyn Byrd Beverly Douglas and practiced law in Richmond to support his growing family. From 1883 to 1885, he represented his home state in the United States House of Representatives. Later, Wise ran for state governor on the Republic ticket, but lost to Fitzhugh Lee. Toward the end of his life, he moved north and spent time writing his memoirs, works of fiction, and articles for veteran publications.

From hopelessness to reassembling his life, John Wise faced the realities that many young men struggled with at the end of the Civil War. They had to realize the differences between their ideals, make peace with what they had witnessed during the war, and find the resolve to rebuild their lives for the uncertain future.

Sources:

[i] Wise, John. The End of an Era: The Story of a New Market Cadet. 1899.

[ii] Ibid., Page 127

[iii] Ibid., Page 234

[iv]Ibid., Page 312

[v] Ibid., Page 327

[vi] Ibid., Page 364

[vii]Ibid., Page 365-366

I had to laugh at his mention of a “freak museum”. Mr. Wise owes a LOT to quite a few museums then, haha. I’m sure John’s experience and sentiments were shared by many young men trying to piece their lives together in the years following the surrender. Thanks for the post 🙂

Enjoyable article- how unique that Wise and Meade were related and apparently cordial.