The Civil War and General Jim Mattis: A Closer Look at Call Sign Chaos (Part 1)

The first time I heard Jim Mattis speak was in 2007. As an Education Director for the U.S. Marine Corps, I attended then Lieutenant General Mattis’ seminar on the 1st Marine Division at the First Battle of Fallujah (2003). This was a Marine lecture—interactive, with “oorahs” and “yeah, let us see that video clip again”! I loved it and even joined in the hoopla. From then on, I paid attention every time the name ‘Jim Mattis’ came up; and, in the fall of 2019, I got the chance to learn a lot more when I read Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead by Jim Mattis (Gen. USMC, Ret.) and Bing West. I didn’t read it for blog ideas, but the list of ideas kept coming. In addition to the stand-alone blog I wrote about Generals Jim Mattis and Robert E. Lee (“Be not ashamed to say you loved them”), I was motivated to write a two blog series. This is the first of the series in the form of a closer look at the book and how and why it inspired me.

The first time I heard Jim Mattis speak was in 2007. As an Education Director for the U.S. Marine Corps, I attended then Lieutenant General Mattis’ seminar on the 1st Marine Division at the First Battle of Fallujah (2003). This was a Marine lecture—interactive, with “oorahs” and “yeah, let us see that video clip again”! I loved it and even joined in the hoopla. From then on, I paid attention every time the name ‘Jim Mattis’ came up; and, in the fall of 2019, I got the chance to learn a lot more when I read Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead by Jim Mattis (Gen. USMC, Ret.) and Bing West. I didn’t read it for blog ideas, but the list of ideas kept coming. In addition to the stand-alone blog I wrote about Generals Jim Mattis and Robert E. Lee (“Be not ashamed to say you loved them”), I was motivated to write a two blog series. This is the first of the series in the form of a closer look at the book and how and why it inspired me.

Call Sign Chaos is a primary source and is a teaching tool for current and future leaders, as well as students of history, leadership, and politics. The book illustrates how Mattis learned to lead, applied historical lessons, used different leadership approaches, and either overcame, or could not overcome, frustrations. The authors succinctly cover these subjects by dividing his forty-four years in the U.S. Marine Corps into the three phases: direct leadership covers twenty-nine years; executive leadership spans seven years; and strategic leadership traverses eight years. What the reader gets is a behind-the-scenes tour—from second lieutenant to a four-star general. Mattis credits his success to his mentors (commanding officers and Vietnam veterans) and his love of reading history.

With 9,000 books in his library, “warrior-scholar” should be added to the list of monikers for Mattis. Though partial to studying Roman leaders and historians, he also enjoys reading works on the American Civil War and broader military subjects as well. When he reads, he critically thinks, and he encourages others to do the same. “If you haven’t read hundreds of books, learning from others who went before you, you are functionally illiterate—you can’t coach and you can’t lead. History lights the often dark path ahead even if it’s a dim light, it’s better than none.” The authors expand on this quote by providing numerous examples of how historical leaders and events guided Mattis through complex, volatile situations. There is not time or space to look at all the commanders, but herein is how a Roman general and several Civil War generals lit that dark path for him.[1]

Mattis was a critical thinker at an early age. As a second lieutenant, his company commander encouraged him to read Strategy by Liddell Hart and Lee’s Lieutenant’s by Douglas Freeman. He absorbed the lessons. He learned from Major General Thomas Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign (1862) that audacity coupled with thorough planning could prevail over numbers. It was not, however, a principle he put into action as a junior officer. In fact, he did not see much combat during these years. He instead bided his time, training and reading books—including ones about Union generals.

Opportunity to put leadership lessons into a battle scenario arrived during Desert Storm in August 1990–February 1991. Mattis had risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel and commanded 1st Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment. He not only looked to Lee when he tried to balance his love for his men against the need to order them into harm’s way but also Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant. How? When Mattis’ battalion was ambushed, he emulated Grant’s ability to remain unyielding as all was “flying apart” and to maintain the “mental agility to adapt when [his] approach” was not working.[2] Using Grant’s command style allowed Mattis’ battalion to gain the upper hand and push forward with the main assault. The Americans and their allies destroyed the enemy forces in just 100 hours. Desert Storm was over.

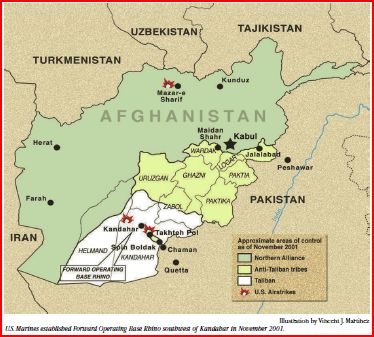

The next ten years were spent preparing for the next war. That came in 2001. In November, Brigadier General Mattis was given command of Task Force 58 and sent into southern Afghanistan to work with a Special Forces unit. The operation was dubbed: Operation Rhino. TF 58 opened a base of operations and went on the offensive, controlling the roads in their sector, isolating and threatening Kandahar. The mission confounded the enemy leadership in northern Afghanistan, and the Taliban and Al Qaeda were forced to divide their attention and resources between defending the north and south. Rhino reminded Mattis of the way Major General William T. Sherman’s fast-moving campaigns developed. He would threaten two objectives, and once the Confederates split their forces, he struck hard and fast at his intended target. Like Sherman, Mattis’ task force and other supporting units took advantage of their enemies’ confusion and within six weeks Kandahar was captured.

Upon his return to the states in 2002, Mattis was promoted to major general and given command of the 1st Marine Division. One of his first directives was to assign his division a motto: “No better friend, no worse enemy.” A phrase he appropriated from an inscription on General Lucius Cornelius Sulla’s tombstone. (Sulla was a Roman statesman and soldier.) Now, in the planning phase of Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003), Mattis turned again to the Civil War. He remembered during the Vicksburg Campaign (1863) Grant reduced the number of tents his army carried, allowing them the freedom to maneuver and move rapidly. Mattis took this idea and directed his men, including the officers, to give up all “creature comforts.” This allowed more room for food and ammunition, as well as gave the 1st Marine Division the ability to move faster toward their objective inside Iraq. In just three weeks, the division accomplished their main objective: the liberation of Baghdad.

The march into Iraq is the last time the authors mention a Civil War general, but Mattis’ career was far from over. He continued to apply history’s lessons as he rose through the ranks. In 2004, he earned the rank of lieutenant general and accepted command of the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force and Marine Corps Forces Central Command. He then was nominated for the rank of general in 2007. He served as U.S. Joint Forces Command and NATOs Supreme Allied Commander. In 2010, he took command of U.S. Central Command. He retired from military service after forty-four years as a Marine Corps officer in 2013.

While it was a treat to hear first-hand how Mattis used history to his advantage, I also thought about the three leadership components that aided and hindered him in his career: trust, respect, and communication. He used these elements with skill from second lieutenant to general. No matter what rank he held, he trusted, respected, and communicated with the military personnel below and above him. That said, the politicians he dealt with from brigadier general on up (2001-2013), were not as respectful, sometimes even rude, arrogant, and many times did not trust or listen to his professional advice or communicate with him. Hmm…is there a Civil War example that illustrates what occurs when a political-military relationship achieves trust, respect, and communication?

Stay tuned for Part II.

Sources:

[1] In my undergraduate days, I was a History and Latin major. I took Latin (and some Greek history) so I could study the generals in the classical era.

[2] Jim Mattis and Bing West, Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead (Random House, New York, 2019), 31.

An interesting read. I look forward to the 2nd part.

Thank you 65th NY! I actually added a Part 3 to the series so Part 2 tomorrow…will get 3 done soon. Cheers