The U.S. Marines of 1861

The American Battlefield Trust Conference this year was to have featured a tour of mine about the Marine Battalion at the First Battle of Manassas. It has been postponed until 2021. In the meantime, I wanted to share some of my research into the Marines of 1861. This is Part I of a three-part series.

To understand the Marines at Manassas, it is necessary to first understand the Marine Corps of 1861. Marines of the 18th and 19th Centuries served in a very different Corps than what exists today. Indeed, much of the structure, mission, and ethos of the modern Marine Corps comes from the World Wars and subsequent operations.

Marines in 1861 did not know the Eagle, Globe & Anchor (adopted 1868), the motto Semper Fidelis (1883), or the terms Devil Dog (1918), Jarhead (1950s), or Gung Ho (circa 1900). Bulldogs and Chesty (the Marine mascot today) meant nothing. They did not annually celebrate the Marine Corps Birthday (1920), and if they paid any attention at all may have said it was July 11, 1798, instead of November 10, 1775. There were no regular and permanent Marine regiments, brigades, divisions, or corps/Marine Expeditionary Forces; those all came in 1914 or later.

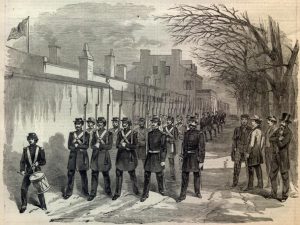

Civil War Marines did have some things in common with the modern Marine Corps: the headquarters at 8th & I Streets SE at Marine Barracks Washington, the band, an early form of the Marine Hymn, service aboard ship and around the world, the term Leatherneck, an emphasis on smart appearance and disciplined drill, aggression in operations, and expeditionary warfare.

Marines of the 18th and 19th Centuries largely operated as small (usually less than 30) detachments of varying sizes aboard U.S. Navy ships. Marines had the mission of keeping discipline among the crew, manning guns or the rigging in battle, and providing parties to board other ships or land ashore. (The current Commandant is trying to push the Marines back toward those roots.) With two notable exceptions, the 200-man battalion in Mexico in 1847 and the 350-strong battalion at Manassas in 1861, this was generally the Corps’ operating pattern until the War with Spain in 1898 and the Boxer Rebellion in 1900.

The U.S. Marine Corps in 1861 numbered 48 officers and 2,338 men. It had one colonel, the Commandant, one lieutenant colonel and four majors for the entire service. Most Marines were scattered about the world on U.S. Navy ships and shore stations. The Commandant was 68-year-old Colonel John Harris of Pennsylvania, a veteran of the Battle of Baltimore in the War of 1812. Twenty U.S. Marine officers, especially some of the most promising junior ones, had resigned and joined the Confederacy.

A call for recruits went out, and young officers and men arrived at Marine Barracks Washington to put on uniforms and the Corps’ insignia of a bugle and M. Harris and the officers at Marine Barracks set about turning these recruits into warriors. The call to battle would come sooner than expected.

Would love to read an emerging civil war book about the marines ! I have always wondered about them. I know that traitor Robert E Lee commanded marines in the capture of John brown at harpers ferry . How did the marines get assigned to Lee or vice versa for that mission? Bob LaPolla

When John Brown launched his raid, the Marines at Marine Barracks Washington were the largest body of organized infantry available in that city. They were assigned to Lee.

@Bob Lapolla,

The legal definition of what would’ve constituted a “traitor” when the Confederacy seceded from the North is open to serious debate when you consider the language of the Declaration of Independence, just as it could be debated in the case of George Washington and the rest of our Founding Fathers rejecting British rule. Have you ever read the Declaration of Independence? The language is definitely there to support the Southern view that the Federal government met the criteria of a “tyrant” whom they could legally and by all natural rights free themselves from by separating from the Union. The British loyalists talked of the American revolutionaries then like you talk about Robert E. Lee now. It just so happened that the American rebels won, so it didn’t matter if the British considered them traitors. Not to mention that the British offered to free African slaves held by the American rebels if they could escape to British-held territory. But I’d be surprised if you’d be as willing to call the American revolutionaries “traitors” who fought to defend slavery as I’m sure you are the Southern rebels of the Civil War.

That said, Robert E. Lee was certainly no “traitor” when he swiftly crushed John Brown and his fellow terrorists at Harper’s Ferry. And those are facts of law. John Brown and his men butchered civilians for simply “being in John’s way” at Harper’s Ferry. John Brown was also put on trial and formally convicted of treason against the United States (the South had not yet seceded and Lee acted on behalf of the Federal government). John Brown was a documented terrorist and a traitor, Robert E. Lee as a Confederate general was fighting as a uniformed officer in what the South considered a legal defense against a tyrannical ruler and an invader.

The problem, at least a problem with your ideas is that the Declaration of Independence is not a formal document of government. It’s just a formal notice to the British that we are leaving the realm. There are ideas there regarding what constitutes the arrangement of the individual 13 colonies, but it is not an organizational document. The Articles of Confederation might help your case more, BUT the Constitution is what the officers swear to protect and defend. And the Constitution replaces the AofC some 80 years before the secession.

@JonWCancel, is seems to me that you’re arguing that the letter of the law is paramount when it comes to the foundational documents of the United States, while completely dismissing the spirit of the law, which is to basically ignore the entire premise on which the United States came into being. What is the point of “upholding and defending the Constitution” if the Federal government has violated the spirit of the law entirely? I guess by your logic, Abraham Lincoln would also be a “traitor” (since this is the term I was specifically addressing with the OP) when he suspended Habeus Corpus in violation of the Constitution. You cannot argue that only the letter of the law applies to the idea of secession in the United States, when secession (or rebellion, it’s the same thing in this discussion) was the process that gave birth to our country in the first place. You can’t just come on here and dismiss the DOI as it applies the question of whether the South had a right to secede from the Union. The South did indeed have a “natural right” to secede – that’s the spirit of the DOI, and the ideas enshrined in the DOI cannot simply be split apart from “the Constitution” anymore than you could chew your own legs off and claim you can walk just fine without them.

So my objection to the OP’s use of the term “traitor” to describe Robert E. Lee stands. Funny how you breezed right past the crux of what I was taking issue with and conveniently overlooked the rank hypocrisy and contradictory logic of the OP. Almost like you don’t have true morals, just like him.

Ever since my husband found out that Robert E. Lee and J.E.B. Stuart were both marines sent to Harpers Ferry to quell John Brown’s raid, he’s had the idea that Lee and Stuart had a close relationship even before the war broke out. Is there any evidence to suggest this? Or that their previous acquaintance with each other had an influence on how they worked together in the Army of Northern Virginia?

I’m not an expert on Harper’s Ferry, but this is what I think I know.

Lee and Stuart weren’t Marines themselves. Lee was a Lt. Colonel in the Army who happened to be on leave, I believe, and at his home in Arlington. Lee was simply given command of the ad hoc Federal force tasked by Winfield Scott to stop John Brown’s raid. J.E.B. Stuart just so happened to be in Washington City at the time and was ordered to go as well. Scott sent who and what he had, at hand, to Harper’s Ferry to deal with the problem.

Also, Lee and Stuart weren’t members of the same Cavalry Regiment in the U.S. Army. Lee was in the 2nd Cavalry and stationed in Texas.

Stuart was in the 1st Cavalry and stationed in Kansas.

It was happenstance that Stuart ended up with Lee at Harper’s Ferry. Stuart was in Washington trying to patent an invention of his when he got word of the raid. He volunteered his services and was told to report to Lee. However, they would have known each other from Stuart’s time at West Point. Lee became superintendent in 1852, when Stuart was halfway through his academics there, and among Stuart’s best friends was Lee’s son, Custis.

To Bob LaPolla et all – The first book of a series of five about the Civil War Marines has just been published this year (2021). It’s titled: THE FORGOTTEN MARINES – “Prelude to Civil War, Harper’s Ferry, October 1859.” It answers your question about Lee as well as other questions you may have. More information about the series is available at: http://www.sumdalus.com/tfm. The first book is available in Hardcover or Paperback.