Questions of Secession (part four)

part four of five

I’ve been chatting about secession lately with historian Nathan Hall of Richmond National Battlefield Park. Nathan has been studying the topic deeply for many years and recently spoke on it at the Richmond Civil War Roundtable. I think you’ll enjoy his thoughts, too.

Doug: At what times in pre-Civil War history did the question of secession come up?

Nathan: Because the premise of secession had been considered and essentially tabled, it remained an intriguing “what if” scenario in the early years of the republic. In the decades after ratification, secession was never actually attempted, but the threat of resorting to it was used, periodically, as a political bargaining chip.

Western settlers in Kentucky and Tennessee considered seceding from the U.S. to become Spanish subjects in the 1780s, because of their dependence on the Mississippi River for commerce. In the “Whiskey Rebellion” of the 1790s, Pennsylvanians violently resisted efforts to collect federal taxes, illustrating the difficulty in solving Patrick Henry’s dilemma of whether “the people” or “the states” were the ultimate repositories of sovereignty in the republic.

Outrage over the Alien and Sedition Acts at the end of the 19th century prompted urgent debates over what remedy existed to oppose a law that was unconstitutional. Madison wrote “The Virginia Resolution,” suggesting the state governments, acting collectively, could oppose unconstitutional laws. Thomas Jefferson’s more radical “Kentucky Resolution” claimed that individual states could “nullify” an unconstitutional federal law, without the need to secure the cooperation of other states. It also declared that the federal union was a “compact” of states, rather than a perpetual union. Meaning that it was an agreement from which any of the parties involved could withdraw from at will. No other states ratified the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, and a few years later, in 1803, the United States Supreme Court, asserted for the first time that it possessed to sole authority to determine the legitimacy of federal legislation.

For the next thirty years, states occasionally revived Jefferson and Madison’s concepts. New England States tried to oppose the constitutionality of President Jefferson’s Embargo Act in 1807, and considered the path of secession at the Hartford Convention in 1814-15 to escape participation in the War of 1812, but could never muster widespread support.

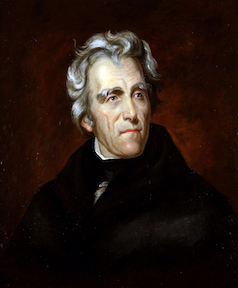

In the 1830s, South Carolina revived the compact theory and the idea of unilateral nullification, in response to federal tariffs. President Andrew Jackson refused to acknowledge that South Carolina had a legal basis for nullifying federal law, warning them, “They know that a forcible opposition could alone prevent the execution of the laws, and they know that such opposition must be repelled. Their object is disunion, but be not deceived by names; disunion, by armed force, is TREASON.” In the face of Jackson’s threats, South Carolina backed down, and the bargaining chip of a secession threat was pocketed once again. On May 1, 1833, Jackson wrote his opinion of what the nullification crisis portended for the future. “The tariff was only a pretext, and disunion and southern confederacy the real object.” He then predicted, “The next pretext will be the negro, or slavery question.”

As questions of slavery and its expansion into the western territories grew to dominate political discourse in the 1840s and 50s, talk of secession once again shifted its base to the northeastern United States. There, frustrated antislavery advocates were losing faith in America’s constitutional machinery to effect meaningful change in the direction of abolition. In 1845, William Lloyd Garrison of Massachusetts sounded the call for disunion thus: “Henceforth, the watchword of every uncompromising abolitionist, of every friend of God and liberty, must be, both in a religious and political sense-‘NO UNION WITH SLAVEHOLDERS!’” Garrison was a member of the “Worcester Disunion Convention,” which met in 1857, “to consider the practicability, probability, and expediency, of a Separation between the Free and Slave States.” Finally, with Abraham Lincoln’s election to the presidency in 1860, secession advocacy returned to the South and swiftly transformed theory to reality.

To be concluded….

The Alien and Sedition Acts were drafted at the end of the 18th Century (in 1798), not the Nineteenth!x

Good catch – I’ll have a strong talk with my editorial board about letting that typo slip by, ha.

It’s interesting to read that someone from Massachusetts, a free state, made a case for disunion over the issue of slavery and there were enough people of the same mind to form a committee for it. I had always believed that it was the south shouting the loudest for secession. It gives some pre-war context to the appearance of Copperheads who wanted the south to stay separate from the Union. It’s definitely a different angle on the question of secession and something I hadn’t thought about before. Fascinating!

Of course the Copperheads didn’t really gain that much strength until ca. 1864, by which time many in the North were becoming war-weary, and that fact was starting to eclipse ideals in causing a desire for a peace settlement of some type..

Actually, there is no direct evidence that I’ve seen that secession was even mentioned at the Hartford Convention. It’s not in the report, it’s not in the convention’s journal, and its not in any of the correspondence I’ve seen from the members of the convention.

“The character of the twenty-six delegates at the convention also boded well. George Cabot, Nathan Dane, and [Harrison Gray] Otis headed the Massachusetts delegation; Chauncey Goodrich and James Hillhoun, the Connecticut delegation; and Daniel Lyman and Samuel Ward the Rhode Island delegation. Except for Timothy Bigelow and perhaps one or two others, all the delegates were moderates, hardly the sort to promote violent measures. Radicals like Blake, Quincy, and Fessenden were purposely excluded from the meeting.” [Donald R. Hickey, The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict, p. 275]

The convention, dominated by moderates, had perhaps as many as three radicals. “The only known radical, Bigelow, was given no committee assignments and apparently did not play a major role in the proceedings. Nor was there any sign of disunion.” [Ibid., p. 277]

The Secretary of the Hartford Convention, Theodore Dwight, published the journal of the convention during the Nullification Crisis, when people were claiming the Hartford Convention had been secessionist. In his book in which he published the journal, he defended the Hartford Convention from these charges of its being a secessionist convention:

“The case of the Hartford Convention appears, then, to be summarily as follows:–It was legitimate in its origin, in no respect violating any provisions of the constitution of the United States, either in its letter or its spirit. The commissions given to the members were scrupulously guarded against any unconstitutional conduct on the part of the Convention, giving them authority only to confer together, and recommend such measures to their principals as they might deem expedient, taking care to govern themselves by a regard to the duties and obligations which the states owed to the United States. The account of their proceedings shows that they punctiliously observed the injunctions contained in their instructions; and the result of their deliberations proves their conduct to have been, in every respect, strictly constitutional.

“Notwithstanding the vast amount of calumny and reproach that has been bestowed upon the Hartford Convention by the ignorant and the worthless, it will not be a hazardous assumption to say, that henceforward no man who justly estimates the value of his character for truth and honesty, and who, of course, means to sustain such a character, will risk his reputation by the repetition of such falsehoods respecting that body, as have heretofore been uttered with impunity. No man, with the facts before him, can do this, without sacrificing all claim to veracity, and, of course, to integrity and honour. Nor will the subterfuge that the journal and report of the Convention do not contain the whole of their proceedings, save him from the disgrace of wilfully disregarding the truth. Nearly nineteen years have elapsed since the Convention adjourned, and no proof has been adduced, and nothing nearer proof, than the unsupported assertions of the corrupt journals of political partizans [sic], of any measure having been adopted or recommended by the Convention, besides those contained in the journal and the report. If there was any treason, proposed or meditated, against the United States, at the Convention, it must have been hidden in as deep and impenetrable obscurity, as the fabulous secrets of free masonry are said to be buried, otherwise some traces of it would have been discovered and disclosed to the public before this late period.” [Theodore Dwight, History of the Hartford Convention: With a Review of the Policy of the United States Government, Which Led to the War of 1812, New York, 1833, pp. 401-402]

“From December 15 to January 5 the convention met behind closed doors, and no one, either then or since, ever obtained a complete record of its deliberations. The little information that the administration did receive from those observing the convention, however, was generally encouraging. Jessup’s predecessor in Connecticut, Colonel Joseph Smith, for example, reported to the War Department that he doubted whether the convention would attempt ‘open rebellion’; it would try instead to give ‘tone, confidence, and system to an opposition which shall continue its equivocal course, possessing all the moral qualities of treason and rebellion and at the same time avoiding a liability to their penalties.’

“[Colonel Thomas] Jessup, while en route to Hartford, met with Governor Tompkins in early December and learned that the New Yorker likewise questioned whether the convention would do much more than complain, issue an address to the people, and then go home. The leaders of the Republican party in Connecticut shared this view, informing both Jessup and Monroe that the thin attendance at Hartford–Vermont and New Hampshire were not officially represented at all–was hardly representative of New England opinion as a whole, and that many of the delegates, especially those from Connecticut itself, were not advocates of secession. Connecticut had accepted the call for the convention only with the reservation that its activities would be consistent with the state’s obligations as a member ‘of the national union,’ and much of the Connecticut debt was invested in lands in New York and Ohio to provide money for the state school fund. Furthermore, it was not difficult for Republican newspaper editors to provide other examples of New England’s very considerable dependence on trade and investments with other parts of the Union and to make the point that disunion would cost the states involved far more than it cost the United States itself.” … That there were extremists in New England who would have welcomed secession Jessup never doubted, but in retrospect it seemed clear to him that they had controlled neither the Federalist party nor the Hartford Convention.” [J. C. A. Stagg, Mr. Madison’s War: Politics, Diplomacy, and Warfare in the Early American Republic, 1783-1830, pp. 479-483]

The Hartford Convention was called to address some serious concerns the New England states had with the way the Madison Administration was governing. The War of 1812 was a major issue, but so was appointing immigrants to office. Additionally, slavery issues were another key point of contention. The 3/5 clause gave disproportionate political power to the slave states, and expansion of slavery into the territories would lead to more slave states and more slave state power. The convention was called to address these concerns. Conventions were a popular method of addressing grievances in the antebellum years.

It’s true that some Federalist hotheads in New England, not at the Hartford Convention, were calling for secession, but they were a tiny minority with little chance of actually effecting such a policy.

The Hartford Convention’s proceedings were held in secret. As politicians do, their political opponents took advantage of the opportunity to denounce the Federalists with the most politically debilitating charge they could think of in order to gain support and poison the audience against whatever the convention would come up with. The worst charge at the time was to be disunionist. It worked. The charges hastened the demise of the Federalist Party.

Thanks for sharing so much detail about the Hartford Convention – really excellent stuff. The idea that it proposed secession is, based on the evidence, clearly more of a political bugaboo than reality. Your analysis of how the charge of disunion could be weaponized by southerners and northerners alike adds a lot to the discussion.

It brings to mind Robert E. Lee’s letter to his son in 1861, when the perception still lingered that New England had advocated secession been condemned for it, true or not. “In 1808,” Lee recalled, “when the New England States resisted Mr Jeffersons Imbargo [sic] law & the Hartford Convention assembled secession was termed treason by Virga statesmen. What can it be now?”

You’re not seriously saying there is no evidence that the HC ever discussed secession are you?!

The Report it produced teens with direct evidence they considered this very much!

There are several insightful elements to “Questions of Secession (part four)” and it is difficult to address them all…

The “more Perfect Union” promised by the Constitution of 1787 was founded on compromise. An agreement founded on compromise only works if all parties abide by terms of the compromise. Like it or not, continuation of slavery was accepted as a condition of Southern States ratifying the United States Constitution in 1787 and 1788. As time went on, one of the elements of this compromise (fugitive slave recovery) was eroded by Northern States enacting State Law attempting to override the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. This was addressed by the Taney Court in 1842 Prigg v. Pennsylvania with Supreme Court 8 – 1 decision overturning State Law.

As regards Massachusetts Abolitionists… there have always been malcontents, and those “following a moral path to a Higher Calling.” The challenge for any republic is to determine the viability and public acceptance of progressive movements, and the timeliness of instituting change. At the same time abolitionists were making demands, other groups were anti-Mormon; anti-Native American; anti-immigrant; anti-Masonic Movement… and some of this can be sorted through politics and the ballot box; some movements die a natural death (or gain universal acceptance); and the rest must be determined by the Courts.

Disunion was floated by abolitionists in the Northeast. And it was floated by attendees of the Nashville Convention of June 1850, during which delegates from Southern States discussed the growing Northern outcry against slavery; and how best to respond. After 1850 there were annual “Southern Commercial Conventions” held at different sites (for example Knoxville 1857, Montgomery 1858) that discussed Southern outlooks, and how best to politically achieve Southern goals. As Northern Abolitionists pushed for an end to slavery, attendees at Southern Commercial Conventions advocated for expansion of slavery into southern California, federal territories, Cuba, Central America… and an eventual resumption of the Slave Trade with Africa.

With such opposing views, strengthening on both sides, it is now clear that “something needed to be done to settle the impasse, once and for all.”

But unilateral secession was not the answer (as proven by subsequent events.) Resort to the Courts was the only acceptable way out of the Perfect Union. And yet, this path was not taken. And, with every Justice of the Supreme Court being an appointee of Democratic Presidents (in 1860) and liable to find in favor of Southern States, the real question to be asked: “Why was the Supreme Court not approached to effect the separation?”

I’ve often wondered exactly the same thing – why such a potentially friendly Supreme Court was not approached to make its ruling on the separation of the Union before resorting to armed conflict. Your question is one of the most significant in the history of American secession, and one to which I’ve never found a satisfactory answer.

The easiest interpretation might be that as the secession crisis was touched off by a relatively small group of 169 men in South Carolina, that they were either a hotheaded group who specifically preferred war to adjudication and ended up pulling everyone else along for the ride, or that they were uniformly delusional in thinking they simply would not be opposed in their separation.

A more complex theory might suggest that those men in South Carolina were aware that a ruling in their favor might not be enough to actually secure their separation. Think of Andrew Jackson’s refusal to enforce the court’s ruling in the Cherokee Cases in the 1830s, which laid bare the chilling reality that a Supreme Court decision unsupported by the force of at least one of the other branches of government was a dead letter.

South Carolina secessionists knew they lacked the support of the legislative branch (hence their resorting to unilateral secession) and could be confident that Lincoln as an executive would oppose them as well, potentially leading to an empty victory in the judicial branch. I’d be curious if the available sources indicate that any of these factors were considered among the disunionists of 1860.

The body of prewar case law is inconsistent with a unilateral secession, which is secession without the consent of the other states, being a legal act. Additionally, they would have to bring suit to say that they were no longer a part of the United States. If they claimed they were no longer part of the United States, they would no longer recognize the authority of the Supreme Court to rule on their status.