Seven “Persons of Importance”

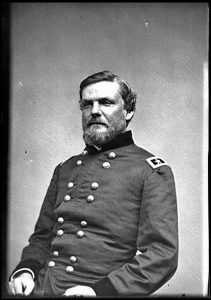

In the early morning hours of May 17, 1865, off the far southwestern cape of mainland Florida, pickets stationed there by Union General John Newton intercepted a small vessel bound for Cuba. That promontory, jutting out into the Gulf of Mexico, Cape Sable. Today, the cape is preserved, not for its connection to the Civil War, but within the confines of Everglades National Park, and the critical habitat of the Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow.

Lieutenant J.J. Hollis of the 2nd Florida Cavalry (USA) had been sent with a detachment to Cape Sable on May 9 with the sole purpose of “to intercept any parties who might be making their escape from the Confederacy.” The intervening days was spent in an area filled with mangroves, hardwood hammocks, and dense vegetation, a remote area of Florida even in today’s world. The intelligence gathered and shared by Union authorities in the state of Florida though would ensure their wait in this tropical location would not be in vain.

(courtesy NPS-EVER)

At 2:30 a.m. the occupants of this boat, deemed “persons of importance” by the United States military were taken into custody. This gleaned hope for the operation, which both the army and navy were conducting in Florida and along her many miles of coastline as hostilities were winding down was the was to ensnare fleeing high-profile former Confederates

One week after Confederate president Jefferson Davis was captured near Irwinsville, Georgia, the armed forces of the United States was still on the look-out for the likes of Judah Benjamin, the last Secretary of State in the Davis cabinet and John C. Breckenridge, former vice president of the United States and last Confederate Secretary of War. Both were fleeing and both also happened to be in the state of Florida on May 17.

Initially, according to Acting Volunteer Lieutenant Edward Conroy, in his report from the USS Union to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, mentioned what transpired on that May day:

“General Newton commanding the army forces at Key West, received information that his pickets at Cape Sable, [Fla.], had captured a boat containing 7 white persons and 1 colored, all armed, and to appearance, persons of importance. They had embarked at Crystal River, pulling and sailing along the coast of Florida during the night and secreting themselves during the day. Their object was to get to Havana…Not having been received at Key West, it is not known who they are. Their conduct looks suspicious and leads to the supposition that they were men of importance in the so-called Confederacy, and that many of the names given are fictitious. It is thought Breckenridge and Mallory are among them.

However, the people floating on that boat, were not these luminaries of Mallory and Breckenridge. Although Mallory hailed from Key West and had left Richmond with Davis, he had quit the southward movement in Georgia to seek out his family who were refugees there. He was taken captive by Union forces in La Grange, Georgia on May 20.

(courtesy of NPS-EVER)

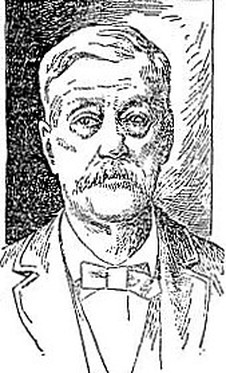

A few of the men on that boat were “persons of importance” of the “so-called Confederacy.” One of the individuals was Thomas A. Harris, former Missouri State Guard brigadier general who had fought at the First Battle of Lexington, Missouri in September 1861, then became a congressman representing Missouri. He did not win reelection in 1864 but embarked on a covert international mission, besides trying to smuggle supplies into the blockaded Confederacy, along with fellow captured shipmate Richard S. McCulloch.

(courtesy Peewee Valley History)

The plan that had been concocted was to attack United States shipping interests and possibly foreign vessels that were sailing toward United States ports. Their goal was to place fire bombs or other explosive devices on board these ships and called for establishing pro-Confederate operatives at these foreign ports. The Confederacy fell before they could fully realize this clandestine warfare plan.

Unfortunately for the naval and army forces spread throughout south Florida, Benjamin and Breckenridge would both evade authorities and spirit their way out of the country, Breckenridge through Cuba and eventually to Canada and Benjamin by way of the Bahamas and to a permanent exile in Europe.

Harris, the most notable Confederate captured on May 17, would return to Missouri, worked in a life assurance company, moved to Texas, before finally settling in Kentucky. Which also happened to be where the person he was hoped to be by Union authorities, John Breckenridge, was from and finished his days.

*Sources*

www.peweevalleyhistory.org (The Harris Years)

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, ser. 1, v. 17, page 853

An Honorable Defeat: The Last Days of the Confederate Government by William C. Davis

Flight into Oblivion by Alfred Jackson Hanna

Thanks for the article. In looking at the sources, I believe the first link has a typo in it. In case anyone is interested in reviewing I found the location below with a single “e”:

https://www.peweevalleyhistory.org/the-locust-harris-years.html

Hey Eric,

Thanks for reading and the typo catch. I have made the correction.

Phill Greenwalt

Excellent reminder that the Civil War did not end with Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of Southerners (former officials, military men, and their families) fled the dying Confederacy and settled in Mexico, and Brazil… some went to Canada; others to Europe. Of these ex-patriots, the most problematic were John Breckinridge and Judah Benjamin: Judah Benjamin as Secretary of State CSA had possible connection to plots against President Lincoln that would have required investigation; and John Breckinridge – VP under Buchanan, who ran for President in 1860 and somehow won a Senate seat; who became a Major General in the Confederate Army and finished the war as Secretary of War – his “inconvenient Truth” related to involvement in the planning and facilitating of preparations for the unilateral removal of a sizeable chunk from the United States with intention of establishing a New Nation… which resulted in a bloody, grievous Civil War. And that participation in planning likely occurred while he was acting as senior official in the United States Government.

Some “missed opportunities” in the quest for fugitives were for the best.

Is there any mention of who the other six “persons of importance” were in the boat along with Harris?

Hey Sheritta,

Thanks for the read and comment. According to the official report filed the other five, besides McCullock and Harris were:

1. Frank C. Anderson

2. Frederick Mohe

3. Julius C. Pratt

4. Isaac A. Homer

5. Henry W. McCormick

Nice article, Phil. Breckinridge, of course, returned to the U.S. after three years in exile, taking advantage of President Johnson’s proclamation of amnesty. Benjamin, after having survived an incredibly harrowing escape to England, was having none of it. He carved out a successful career there as a barrister and then died a natural death at the age of 72 in Paris, where he is buried. For the remainder of his life in England, he never spoke of the American Civil War nor of his role in it. He never returned to the U.S., of course, because he was up to his eyeballs in terror and assassination plots in the final year of the war (spring, 1864, through spring, 1865) and knew he would not escape the hangman. The year of terror was partly a response to the Wistar and Dahlgren-Kilpatrick raids against Richmond in early 1864 (especially Wistar’s orders to capture, and Dahlgren’s orders to assassinate, Davis and his cabinet) and partly the last desperate flailing of a dying Confederacy.

Thanks for the interesting read.

When Phill Greenwalt first posted this report in May, there was “something more to it” that I had run across, but at the time did not fully recollect: both Thomas A. Harris and Richard Sears McCulloch had been mentioned during the proceedings of the Trial of the Lincoln Assassination Conspirators (although both leads were subsequently not followed up.) Still, the relationship of both men to President Jefferson Davis, connecting all three to a Letter from CSA Senator William S. Oldham… and ultimately linking these four with CSA Secretary of State Judah Benjamin… was offered as proof that the Confederacy was embracing Black Flag warfare during its waning weeks.

Thomas A. Harris attended West Point until 1845 (resigned); then was commissioned Second Lieutenant in 12th U.S. Infantry on the day war ended with Mexico. He participated in two filibuster expeditions, then returned to Hannibal Missouri. When the Secession Crisis erupted, Harris pushed for Missouri to go with the South; then joined the pro-South Missouri State Guard (commissioned as Brigadier General.) Prior to contributing to the embarrassing Union Defeat at Lexington Missouri, General Harris led a raiding party south through St. Joseph that collected nearly one hundred wagons full of munitions, food, and booty for the Rebel cause at Lexington. And General Harris may have had a hand in the Platte River Train Disaster of 3 SEP 1861 that sabotaged a bridge and threw an express passenger train into a gully. Among the 100 casualties: Barclay Coppoc, one of the members of John Brown’s Raid at Harper’s Ferry. At the end of the Civil War, General Harris was in Richmond involved in Special Operations.

Richard Sears McCulloch was a native of Baltimore who gained acclaim as Professor of Chemistry (officially “Professor of Natural Philosophy” at Princeton University.) In 1864 he was lured south and threw in his lot with the Confederacy, to work on Special Weapons. One of his last projects, as the Capital at Richmond was evacuated, was a poison gas weapon.