Granger’s Juneteenth Orders and the Limiting of Freedom

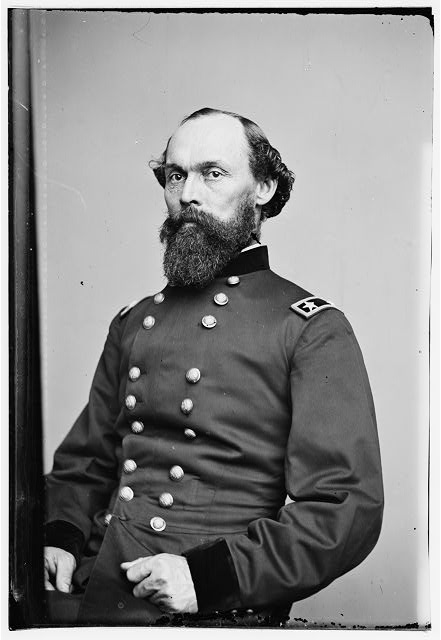

Juneteenth is recognized as the symbolic end of slavery in the United States. Galveston, Texas, held out as a Confederate stronghold after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Once occupied by Union forces, Major General Gordon Granger established his headquarters for the District of Texas on the island on June 18, 1865, and set to work establishing control over the state’s interior. The next day he issued orders asserting that emancipation applied to the area. A closer look at those orders and the ones he issued immediately thereafter, however, reveal that Granger complicity approved of a limited definition of freedom.

The by-now commonly known first section of Granger’s General Orders Number 3 read:

“The people are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.”

From the outset, and with the benefit of hindsight, we see a glimpse of the expectation that slaves would remain on their former plantations. Knowing what we do now about the establishment of sharecropping to take the place of slavery, we can already see the foundation being established that little would change for some of Texas’s Black population, except their compensation. Granger continued:

“The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Almost from the moment Union soldiers entered the southern states in 1861, the enslaved population sought them out as a means to freedom. Union military authorities and the Lincoln administration grappled with the issue of “what shall be done with the slave?” Morality aside, the solution popularly evolved from confiscation as a military necessity to outright emancipation. Despite their various attitudes on slavery itself, many Union commanders nonetheless did not want to also have to now manage the large contraband camps that sprung up in their districts. Granger appeared to go a step further, or perhaps it is better said that he regressed a step back.

On June 18, hours before Granger’s arrival, Galveston’s mayor C.H. Leonard called on Rankin G. Laughlin, Union provost marshal general for the state of Texas. Laughlin appeased many of the mayor’s concerns, and as Leonard was leaving, he met a cotton merchant who had under his charge three men who had escaped from plantations nearby. A local newspaper correspondent reported the discussion on what was to be done:

“The Mayor said that it had been his rule to send all such negroes home, but as the United States authorities were now here he would consult them and accordingly he went back again to the Provost Marshal General; and having stated to him the case, asked him how he would dispose of the negroes, informing him, that the same time, what had been his own rule in all such cases. The Provost Marshal General said, it might be very well to send them to their homes, but as he had work for them to do, he would send them, for the present, to the Quartermaster for employment. This was accordingly done, but the Quartermaster having no immediate work for them, sent them to jail for safe-keeping till he should want them. We mention this as an indication of the policy our Government is now pursuing in relation to runaway negroes.”[1]

Granger arrived later in the day and his proclamation on June 19 reinforced the priority of keeping the formerly enslaved population at work on their respective plantations. In addition to stated worries about lawlessness and private discussions about a loss of political power, the primary concern for Galveston’s authorities appeared to revolve around the impact that emancipation would have on cotton production. Granger satisfied their concerns and complicity assisted in preserving Galveston’s status quo antebellum.

Provost Marshal General Laughlin echoed this sentiment when called upon by prominent Galveston citizens to clarify Granger’s orders. He restated the importance of keeping the freed slave population on their respective plantations as paid employees to both ensure a cotton crop and, in his opinion, to provide the best possible outcome for the Black population. Laughlin naively expected fair negotiating in setting up these new work contracts. When called upon to provide a public statement, he concluded “that it is well known, that the Government desires to furnish every facility to her citizens to resume and continue their usual avocations, and that the public and private interests requires of them as well as their former servants the exercise of perfect and entire good faith in all their civil and domestic relations.”[2]

Some Texans made it clear that expectations of fair contracts had no basis. “Indisposition to work in a state of freedom is the first difficulty,” claimed J.M. Baker of Plantersville. “That immunity from labor constitutes freedom, is the stereotyped idea of the negro. And if left to himself he will, as a general rule, carry out his principles in practice.” Baker further advocated, “The only remedy under heaven for the cure of negro indolence is physical force, such as is exercised by a parent or guardian over minors. Moral force should always precede physical force, but if it fails, then apply the switch.” His solution to emancipation, therefore, was “to force the negroes to remain with their former owners for a number of years, for a fair compensation, until the ingress of white laborers shall supply their places.”[3]

The emancipated Black population had little choice but to accept these contracts and remain on their plantations, as Granger’s subordinates enforced the letter of his orders. The Houston Telegraph noted the process as it occurred:

“We hear that the Federal authorities at Galveston are bringing the negroes to common sense in a summary manner. They call them up, on by one, and ask who they belong to. Those who tell the truth are sent home at once, while those who acknowledge no home or master are put to work on the streets, and on other labor, under the control of the military authorities. Negroes who flatter themselves that the new regime has no labor connected with it will make a grievous mistake.”[4]

The New York Times denounced the Telegraph’s conclusion, stating, “There has been exceedingly little of that [common sense] in that quarter for some time back, and what there was has been rather among the negroes than the white people… We do not hear that the masters were also called up one by one and asked whom they belonged to—and yet unless this was done, what became of the ‘absolute equality of personal rights,’ of which Gen. Granger’s order speaks?”[5]

The New York Tribune’s correspondent meanwhile noticed rampant idleness among the white population of Galveston. “The stores are small and dingy, with nothing to exhibit but empty shelves. The women wait behind the counters, while the sallow-visaged lords loaf on the corners and in billiard saloons.” He believed, “No other Southern city of its prominence and local importance is so utterly insignificant and God-forsaken in its appearance.”[6]

A correspondent for the New York Herald thought otherwise, writing: “While the white man is looking up to prosperity and wealth the negro, on the contrary, is becoming demoralized—lazy, insolent and totally unreliable for steady employment. The advent of Northern soldiers among them has tended to corrupt their minds and fill the same with wild and fanciful notions in regard to and connected with the boom of freedom.”

The correspondent further reported on the influence that Galveston’s ex-Confederate leadership had on the Union military authorities. Mayor Leonard and the Common Council convened on June 27 to address issues they had with emancipation. “One of them was the altered condition of the colored population, which required new regulations for the protection of the citizens,” noted the correspondent. “He regretted to see that some citizens were renting houses to those negroes who had left their employers, thus giving facilities for establishing various nuisances and committing depredations upon citizens. He had received many representations of negroes congregating for improper purposes in the houses they occupied, and of many disorders. He had no power to remedy these evils, unless a sufficient police force be furnished.”[7]

The authorities called on Granger and the following day he issued orders that reflected their concerns:

“All persons formerly slaves are earnestly enjoined to remain with their former masters under such contracts as may be made for the present time. Their own interest as well as that of their former masters, or other parties requiring their services, renders such a course necessary and of vital importance until permanent arrangements are made under the auspices of the Freedman’s Bureau.

“It must be borne in mind in this connection, that cruel treatment or improper use of the authority given to employers will not be permitted; while both parties to the contract will be equally bound to its fulfillment upon their part.

“No persons formerly slaves will be permitted to travel on the public thoroughfares without passes or permits from their employers, or congregate in buildings or camps at or adjacent to any military post or town. They will not be subsisted in idleness, or in any way except as employees of the government, or in cases of extreme destitution or sickness; and in such cases the officers authorized to order the issues shall be the judge as to the justice of the claim for such subsistence.

“Idleness is sure to be productive of vice, and humanity dictates that employment be furnished these people, while the interest of the commonwealth imperatively demands it, in order that the present crop be secured. No person, white or black, and who are able to labor, will be subsisted by the government in idleness, and thus hang as dead weight upon those who are disposed to bear their full share of the public burdens. Provost marshals and their assistants throughout the district are charged with using every means in their power to carry out these instructions in letter and spirit.”[8]

Willard Richardson, the Massachusetts born and South Carolina educated publisher of the Galveston Daily News, approved of this approach. He commented:

“We are glad to learn that Gen. Granger and our Provost Marshal General are both practical men, and not theorists. They look upon emancipation, not as freeing the negro from all obligation to labor, for no human being, white or black, enjoys such freedom, but simply as changing obligation to work without stipulated wages, to an obligation to work for such reasonable wages as may be mutually agreed upon. It is such an obligation as this that is alone consistent with rational freedom, and it is this obligation that we now understand our Federal authorities intend to enforce.

“This is certainly the only sensible and practical view of the subject. It was natural that the negro should suppose that the privilege of living in idleness was the most essential attribute of his freedom, and that which gave his emancipation its chief value.”[9]

The newspaper promoted the idea that it was not just any manner of continued work that was needed, as it supposed on July 2, “It has been demonstrated by the experience of the last three years, that the foreigner or Northern cultivator who has attempted to raise sugar or cotton by the free labor of the blacks, has in every instance met with complete and disastrous failures.” Instead, the ruling class insisted on restoring slavery in everything but name:

“It follows then that the South can only be cultivated by those of tropical extraction whose color fits them to stand the enervating tendencies of hot climates—directed by the intelligent white natives of the South, whose education has qualified him for the business of planting, and whose knowledge of the peculiar habits, and disposition of the dusky races, fits him to direct their labors to beneficial results. If the staples of the South are raised, the native Southerner will have to direct their cultivation. The system of compulsory labor has been done away with, and in its place is proposed to substitute a quasi system of peonage; based upon the mutual consent of the proprietor and laborer.”[10]

Richardson’s paper pointed to previous examples in Mexico and Central America where he thought peonage had been successful because it was “based upon a compulsory system, somewhat allied to that of slavery.” Though the U.S. Congress passed the Peonage Abolition Act of 1867, many states skirted the issue, enforcing their own “Black Codes” that upheld the spirit of that form of oppression. Richardson frequently published letters that advocated similar racist beliefs.

“To give the negro absolute social, civil and political equality would be to bring down ruin and distress upon both races,” wrote James E. Scott of Waverly. “If only the well-being of the negro be considered, it will be found to consist in his continuation in a subordinate relationship to the white race.” For those who would not remain on the plantation, Scott believed, “Jails, penitentiaries, pillories and whipping must be multiplied.” However, he continued, “Happily Gen. Granger feels the pressure of this duty, and has earnestly enjoined the negroes to remain with their masters and has prohibited them from traveling on the public thoroughfares without papers or permits from their employers.”[11]

As Granger moved inland he issued similar orders, announcing in Houston on June 22:

“The Freedmen in and around the City of Houston are hereby directed to remain for the time being with their former owners. They are assured that by so doing they forfeit none of their rights of freedom. An Agent of the Government, whose business it is to superintend the making of contracts between the Freedmen and those who desire to employ them, is expected to be here soon. In the meantime, the Freedmen are advised to be patient and industrious.

“No encouragement or protection will be given those who abandon their present homes for the purpose of idleness. If found in this city, without employment or visible means of support, they will be put at labor, cleaning the streets, without compensation.”[12]

The San Antonio Herald meanwhile advised local planters not to inform their enslaved workers of their freedom, noting “In many cases in this city, entire households of slaves at once quit their homes and took to idleness on the streets, until the nuisance became intolerable, accordingly, in the absence of the Federal authorities, our worthy Mayor a few days ago had these idle negroes arrested, and lodged in jail overnight, and put to work on the streets without pay.” The newspaper boldly proclaimed “emancipation, so far as the negro is concerned, is a mirage—a myth.”[13]

As Granger extended the scope of Union control in the state, Texas newspapers published earlier articles from New Orleans and Mobile attesting to Granger’s character and confidence that he would prove an ally. “One common feeling of regret was manifested that Gen. Granger is soon to leave us,” remarked the Mobile News on June 14 in a widely reprinted article.

“His habit of clear and broad practical thinking, and his great administrative ability, would have helped us signally in readjusting our political relations. He is a man, however, who by force of his genius will create opportunities, and whether in Texas or Alabama, will be as influential in giving a right direction and tone to political ideas as he will be invincible in campaigns and battles. In his high future career which awaits him, and which will unfold itself slowly or swiftly, according as the emergencies are small or great, he will carry with him the abiding confidence and esteem of our whole community.”[14]

Granger certainly inherited a challenging task, one for which even with the benefit of hindsight I cannot offer a perfect solution. He was tasked with both enforcing the Emancipation Proclamation and appeasing ex-Confederates, all while ensuring that year’s cotton crop went to market and determining how to ease the formerly enslaved people to freedom. His actions also represent a common approach that many Union commanders took regarding the status of the enslaved population in their districts, hoping that the Freedman’s Bureau would tackle the issues in the future. Nonetheless, in the early stages of his authority in Texas, the prioritization of cotton production emboldened the planter class. Most had anticipated the end of slavery upon the arrival of Union forces but immediately found opportunity to maintain their economic, political, and social control. The treatment of the Black population as second class remained true after the Freedman’s Bureau’s short-lived tenure in Texas.

Therefore, we find that the conditions written into orders that were supposed to bring freedom for the enslaved also set the tone for non-compliance with the spirit of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. Initial restrictive emancipation in Galveston itself limited the first part of Granger’s General Orders Number 3. Therefore, as we acknowledge and celebrate Juneteenth as a holiday that extended freedom to more Americans, we find strict qualifiers on that freedom set immediately thereafter in the city where it occurred. These seeds would go on to develop into larger systematic oppression, the effects of which we still find impacting our country 155 years after the end of the Civil War.

Sources:

[1] “Editorial Correspondence,” Galveston Daily News, June 20, 1865.

[2] R.G. Laughlin to “Col. H. Washington, E.O. Lynch and Jas. Sorley, Esq.,” June 25, 1865, reprinted in “Importance Correspondence,” Dallas Daily Herald, July 8, 1865.

[3] “The Difficulties of Emancipation and the Cure,” Galveston Daily News, July 9, 1865.

[4] Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph, June 21, 1865.

[5] “The Negro Question in Texas,” New York Times, July 9, 1865.

[6] “From Texas,” New York Tribune, July 7, 1865.

[7] “Our Galveston Correspondence,” New York Herald, July 15, 1865.

[8] “Circular,” Galveston Daily News, July 2, 1865.

[9] Galveston Daily News, June 28, 1865.

[10] Galveston Daily News, July 2, 1865.

[11] Jas. E. Scott to James Sorley, July 13, 1865, Galveston Daily News, July 26, 1865.

[12] Galveston Daily News, June 23, 1865.

[13] Reprinted as “How Does Emancipation Work?” Galveston Daily News, July 16, 1865.

[14] Reprinted in Dallas Daily Herald, July 1, 1865.

Well done. Very informative. A useful addition to the discussion of the Civil War’s aftermath.

Very enlightening, thanks Ed.

Thanks, it’s easy for us to judge because of generations of progressive discussion. One day I imagine my great-grandchildren will ask of my decisions “why,” and wonder why I am so narrow-minded?

Again, thanks Ed

Excellent article! Very clarifying. Thank you, Ed.

Of course neither the 14th nor 15th Amendments had yet been ratified.

This is very well written! Appreciate the insights and balance of the author. Granger was not a white knight on a white stallion. He was a hard working man who did the best he could with what he was given that being a nearly impossible task in an unconquered and hostile environment. His role in the Civil War is often overlooked. We should thank him for his service. BY THE WAY my great-grandfather was among the 2000 troops that escorted General Granger to Galveston and later to Houston. It feels good to be connected with a moment in our history when “freedom and justice for all” was the expectation.