Gettysburg Off the Beaten Path: The First Shot Marker

On the morning of July 1, 1863, the men of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s division strode confidently toward the town of Gettysburg. Heth was a recent addition to the Army of Northern Virginia, having served at brigade and temporary division command at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Since Chancellorsville, General Robert E. Lee reorganized his army, and Heth was the recipient of a second generals star and a division of some 7,458 men. On the previous day, Heth dispatched the North Carolina brigade of Brig. Gen. James Johnston Pettigrew to Gettysburg in search of supplies. Heth later claimed “My men were sadly in want of shoes. I heard of a large supply of shoes were stored in Gettysburg. On the morning of the 30th of June, I ordered General Pettigrew to march to Gettysburg and secure these shoes.” This line has led to the pervasive myth that there was a shoe factory in Gettysburg and that the battle started over shoes. In fact, there was no shoe factory in Gettysburg, and Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s forces had been through the town on June 26th, when Early ransomed the town and demanded provisions for his men, including 1,000 pairs of shoes. Thus, the town had been well picked over before Heth’s men marched east along the Chambersburg Pike toward Gettysburg.

Well short of the town, Pettigrew noticed a force shadowing his men. He, too, claimed that he could hear the “beat of drums (indicating infantry) on the further side of the town.” Pettigrew feared that if his men were to enter the town and split up to capture supplies, this unknown Federal force could disperse or destroy his 2,580 Tar Heels. Heth was unconvinced by Pettigrew’s report. The 34-year-old Pettigrew possessed a brilliant mind. While he did not attend West Point, the Tar Heel attended the University of North Carolina and graduated at the age of 19. He taught at the United States Naval Observatory, traveled the world, and authored a book in the antebellum years. In April of 1861, Pettigrew as a member of the Confederate Army and present at the firing on Fort Sumter. By 1862, he was serving on the Peninsula and was severely wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines in the throat. Now at the head of one of the largest brigades in either army at Gettysburg, Pettigrew worried about the developing situation. Unfortunately for the Confederates, Heth paid gave little credence to his subordinate’s report. Both Heth and Third Corps commander A.P. Hill viewed Pettigrew as a neophyte when it came to the ways of war. Heth and Hill “did not believe that there was any force at Gettysburg, except possibly a small cavalry vidette.” In fact, there was a force of Union cavalry in Gettysburg—two brigades commanded by 37-year-old West Point graduate John Buford. And the force that Pettigrew spied was most likely a squadron of the 8th Illinois Cavalry.

John Buford had seen all he needed late on the morning of June 30. Lee’s army was clearly within striking distance of Gettysburg. Having located at least a portion of the Confederate army, Buford set to work. He established his headquarters in the Eagle Hotel along Chambersburg Street and set up a long, thin picket line of videttes around three-quarters of Gettysburg. From the Hanover Road on the east side of Gettysburg, north to the Carlisle Road then arching down across the Chambersburg Pike, where it finally terminated near the Fairfield Road. Buford’s troopers were able to cover eight of the roads leading into the town from the east, north, and west. Behind the line of videttes were a number of reserve positions that could quickly send troopers to threatened points.

Should the Confederate’s look to push east toward’s Gettysburg, Buford would be ready for them. Buford’s plan to stall a southern advance was a textbook delaying action where he would take advantage of the topography of the region, namely the numerous ridgelines of the area, and the horseflesh on hand.

From Wisler’s Ridge, roughly 3 miles west of town diamond, Federal troopers could fight on foot, three men battling the enemy while a fourth trooper held the other horses. Once the rebel infantry approached too closely, the troopers would take to horse and fall back to the next ridgeline, dismount, and start the battle anew.

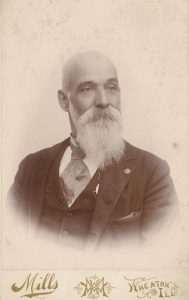

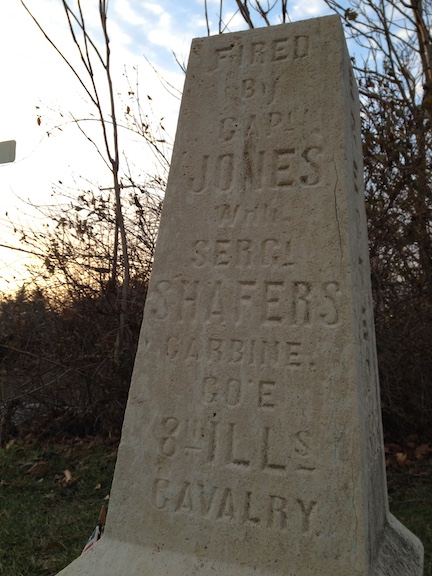

With Hill’s permission, Heth took to the Chambersburg Pike early on July 1. Instead of sending the largely untested brigade of Pettigrew toward what Heth presumed to be a phantom enemy, he went with the veteran Alabama/Tennessee brigade of Brig. Gen. James J. Archer. Archer’s men approached Marsh Creek at the base of Wisler’s Ridge. Filing across the creek the men of Heth’s division were spied by the forward unit of Buford in the area a vidette of four troopers commanded by Sgt. Levi Shaffer. Shaffer called back to the Herr Tavern to the officer in the area, 1st Lt. Marcellus Jones. “The Johnnies are coming,” declared a winded trooper. Jones fired off a message to his commanding officer Maj. John L. Beveridge reporting the enemy movements, and Jones mounted and rode to the outpost.

Jones arrived at the home of Ephriam Wisler, where the enemy was pointed out to the young lieutenant. Turning to Shaffer, Jones asked for the use of the sergeant’s carbine. Utilizing a nearby fence as a makeshift firing platform, Jones leveled the carbine and squeezed off a round.

* * *

The Battle of Gettysburg began in the yard of Ephraim Wisler (sometimes spelled Whistler). Wisler was 31 years old at the time of the battle and a blacksmith by trade. His home, a two-story brick structure was built in 1857. On the morning of July 1st Wisler stepped into the middle of the Chambersburg Pike (modern-day Route 30), “Noticing certain strange movements and actions of small bodies of armed men in the vicinity of the house….Mr. Wisler stepped from the gate opening from his yard to the pike to observe what was going on.” Suddenly a Confederate shell smashed into the road near the young blacksmith. Though he was not hit by the shell, Wisler was never the less shell shocked and “became completely prostrated.” He went back into his home, took to his bed, and died of heart failure on August 11, 1863, leaving behind a widow and two children.

Wisler’s home was sold to James Mickler shortly after the Civil War. Mickler served in Bell’s Adams County Cavalry Company during the June 26, 1863, Battle of Marsh Creek. The home remained in private hands until 2002 when the home was purchased by the National Park Service and is part of a 3.79-acre plot of land owned and maintained by that agency.

In the front yard of the home, which is adjacent to modern-day Route 30, is a small monument which was placed in 1886 by Jones and his pards, and marks the relative location of the first shot of battle at 7:30 AM July 1st.

While standing at the monument turn and look at the western side of the house. Notice the pocked mark brick on this side of the home, which was subjected to small arms fire of the 13th and 5th Alabama Battalion. The infantry skirmishers were firing uphill, which meant many of their shots strayed high. The Federal troopers were also subjected to southern artillery fire from the guns of Capt. Edward Marye’s Fredericksburg Artillery. Marye unlimbered one 3-Inch Ordnance Rifle in the middle of the Pike, near the Samuel Lohr Farm. Marye’s battery was the first Confederate cannon to engage the Federals at Gettysburg.

In this area were also the first casualties of the battle. On the north side of the Chambersburg Pike advanced the men of the 5th Alabama Battalion, who were subjected to the fire of the 8th and 12th Illinois Cavalry, who had dismounted and were ordered to use the top rail of a fence to level their guns and fire on the advancing foe. The fire from the troopers met their first target Pvt. C. F. L. Worley of Company A, 5th Alabama Battalion, who was shot in the leg. On the Federal side, Pvt. John Weaver of Company A, 3rd Indiana Cavalry was also shot in the leg. Weaver was the first Federal mortally wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg, his leg was amputated, but Weaver died on August 3rd, 1863 at Camp Letterman a Union general hospital established on July 22nd to take care of the wounded left behind at Gettysburg. There are at least two other Federal soldiers that claimed to be the first wounded in action, Cpl. Gabriel Durham and Pvt. Ferdinand Ushuer both of the 12th Illinois Cavalry. Both men were hit by artillery shrapnel in the area, both survived their wounds. And still, others claim to have been the first to fire the shot that “opened the ball,” at Gettysburg.

To Reach the First Shot Location:

From the town square.

-Follow Chambersburg Street west for three blocks.

-At the Y intersection bear to the right onto the Chambersburg Pike-Route 30 West.

-Follow Chambersburg Pike-Route 30 West for 2.72 miles.

-Turn left onto Knoxlyn Road.

-Just past the first house and garage on your left will be a small parking area for about two cars. Park here. (Please do not park in the garage or driveway of the adjacent homeowners.)

-Exit your car and walk back along Knoxlyn Road to the Chambersburg Pike. You will see the Wisler House and the First Shot Marker in front of you.

-Please use EXTREME caution when crossing the Chambersburg Pike!

I am enjoying these “off the beaten path” reports; but it puts me in mind why Gettysburg was preserved in the first place: determination of the “hardest fought, most significant battles.” President Lincoln’s appearance likely sealed the deal for Gettysburg; the Veterans, themselves, decided on the preservation of Vicksburg, Antietam, Shiloh, Chickamauga and Chattanooga. It could be argued that Island No.10 and the New Orleans Campaign and the Campaign to turn Fort Columbus (and many others) were equally significant. But those other sites remain off the beaten path; and many are remarkably pristine, waiting for true enthusiasts to seek out and explore.

Many years ago a friend and I decided to find the First Shot Marker. (Its location was just an arrow pointing off his map.) We didn’t spot it until the third time we drove by. I had been expecting something akin to the Eiffel Tower (well, a slight exaggeration), but it was actually dinky enough to be almost totally obscured by some bushes. Hooray, the bushes have vanished!

My great-grandfather, Augustine Bardwell, was with Company A of the 3rd Indiana Cavalry and I believe he was one of the troopers sent forward as a vedette that day. I don’t know exactly where he was positioned. He was also known as Augustus Bardwell.