Gettysburg Off the Beaten Path: The “Wounding” of Richard Ewell

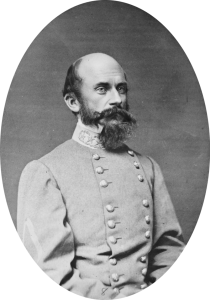

Arguably the most criticized member of the Confederate high command at Gettysburg was 46-year-old Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell. Ewell assumed command of the Confederate Second Corps prior to the Gettysburg Campaign, and after the death of Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. At the August 28, 1862, Battle of Groveton, the prelude to Second Manassas, a bullet struck Ewell in the left leg shattering the patella and the head of the tibia, lodging in the muscles of his calf. The leg was amputated the next day, leaving Ewell out of the war for the next nine months. Now at the head of Jackson’s old corps, he was one of the ranking officers in the army (third in command only behind James Longstreet). Ewell was blessed “[w]ith a fine tactical eye on the battle field,” but “he was never content with his own plan until he had secured the approval of another’s judgment…”

Second Corps staff officer Alexander “Sandie” Pendleton wrote, “The more I see of him [Ewell] the more I am pleased to be with him. In some traits of character he is very much like General Jackson, especially in total disregard of his own comfort and safety…He is so thoroughly honest, too, and has only one desire, to conquer The Yankees. I look for great things of him, and am glad to say that our troops have for him a good deal of the same feeling they had towards General [Stonewall] Jackson.”

Richard Ewell and his 21,806 man Second Corps had performed outstanding work in the Gettysburg Campaign thus far. Moving down the Shenandoah Valley, Ewell and the Second Corps had won stunning victories at Second Winchester (June 13-15) and Stephenson ‘s Depot (June 14). Confederates had captured 3,856 men, 23 cannon, and over 200,000 rounds of ammunition, 300 supply wagons, and over 300 horses. By late June, the Second Corps cut a swath across southcentral Pennsylvania and threatened the capture of the state capital—Harrisburg.

On the morning of July 1, Ewell marched his corps to the sound of the guns at Gettysburg. His corps approach along the Carlisle Road, the Harrisburg Road, and the Chambersburg Pike. While one division was roughly handled on Oak Hill and Oak Ridge, another managed to strike the Federals on the right flank, and dislodge the Yankees from their position north of the town. This sweeping victory led to one of the greatest controversies of the battle when the Confederate high command failed to follow up and attack Culp’s and Cemetery Hills. (You can read an extended examination of those actions by clicking here.)

After July 1, the movements of Richard Ewell are difficult to follow. On the morning of July 2nd, we know that he inspected the Culp’s Hill sector with one of Lee’s staff officer, he met with Lee later that morning, and he also scouted artillery positions with Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early, among other Ewell sightings. That same day, the Second Corps bombarded Cemetery Hill, assaulted Culp’s Hill, and temporarily broke through the Federal line on East Cemetery Hill.

On July 3rd, the fighting at Culp’s Hill roared back to life around 4:30 AM and was sustained for the next seven hours. Near noon, Ewell materialized on the southeast edge of the town, in the vicinity of Brig. Gen. Harry Hays Louisiana Brigade. The Creoles endured harassing sharpshooter fire throughout the Battle of Gettysburg. On July 2, they lost anywhere between 45 and 67 men to Federal sharpshooter activity, and they spent much of the 2nd clinging to a lip of ground on the southern edge of Winebrenner’s Run.

July 3rd brought more Federal sharpshooter activity into this area of Ewell’s line. Between noon and 1 PM, prior to the pre-assault bombardment for Pickett’s Charge, Ewell rode to Hays’s brigade. Richard Ewell was “as a compound of anomalies, the oddest, most eccentric genius in the Confederate Army…No man had a better heart nor a worse manner of showing it,” declared one staff officer. “He was in truth as tender and sympathetic as a woman, but, even under the slight provocation, he became externally as rough as a polar bear, and the needles with which he pricked sensibilities were more numerous and keener than porcupine quills. His written orders were full, accurate, and lucid; but his verbal orders or directions, especially when under intense excitement, no man could comprehend. At such times his eyes would flash with a peculiar brilliancy, and his brain far outran his tongue.”

Ewell and staff officer Captain Henry Brown Richardson sat on horseback peering toward the Federal lines. Warned by some of Hays’ men that Federal sharpshooters were active in the area, Ewell scoffed, claiming that the enemy was “fully fifteen hundred yards distant,” and “that they could not possibly shoot with accuracy at that distance & that he would run the risk of being hit.” The brave and stubborn Ewell proceeded with his self reconnaissance, ala Stonewall Jackson, not heeding the good advice of his subordinates.

Moments later Richardson was struck in the back by a Federal ball, the bullet pierced his back and bruised his lung, leaving the engineer officer severely wounded. While Ewell only had one leg, and he rode for distances in a carriage, he was still as nimble on a horse as a cowboy on the plains, according to one admirer. Ewell dismounted and helped the stricken officer, most likely feeling sheepish for his disregard of the commonsense suggestion from others, and for misjudging the distance to the Federal lines.

After Richardson was looked after, the General admitted that he, too, had been hit by enemy fire. Luckily for Ewell, he was struck in his wooden leg. He asked an aide to “hand me my other leg.” After replacing his prosthesis Ewell went on his way. He later quipped to Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon, “suppose that ball had struck you: we would have had the trouble of carrying you off the field, sir. You see how much better fixed for a fight I am than you are. It don’t hurt a bit to be shot in the wooden leg.”

While Ewell survived his “wounding,” and remained with the army during its retreat from Gettysburg, Richardson was not so fortunate. The native of Winthrop, Maine, and antebellum civil engineer in Tensas Parish, LA., Richardson joined Company D, 6th Louisiana in June of 1861. He served as an orderly to Ewell in 1862, and was wounded at Antietam that same year. After serving as an engineer on Early’s staff, he again joined Ewell’s staff in June of 1863. His wound proved far too serious and he could not be removed with the Confederate wounded when they evacuated Gettysburg. Richardson was captured by Federals on July 5 and held at the Federal prisoner of war camp at Johnson Island. He was not paroled until May 26, 1865, (another source states Feb. 11, 1865). He returned to Louisiana, serving as the state’s chief engineer until his death in 1909. Richardson was remembered in his obituary as “one of its [the Mississippi River Commission’s] most experienced and able members and the State of Louisiana…most distinguished civil engineer.” He lies in an unmarked grave in the famous Metairie Cemetery, in New Orleans.

Author’s Note: Why Third Corps commander A. P. Hill is forgiven by buffs and veterans for starting the Battle of Gettysburg, and then mismanaging the affair on his part from July 1-3, while Ewell, Stuart, and Longstreet have been lambasted for decades has baffled me for years. It’s another story for another time, but never forget that Hill is as much to blame for Confederate failure on July 1 as Richard Ewell. And you can read more here.

To Reach Ewell’s Wounding Location:

From the town Square.

-Follow York Street for two blocks east.

-Turn right onto Liberty Street.

-Follow Liberty Street for three blocks.

-Continue straight onto East Confederate Ave.

-Park at the first pull off that you come across on the right-hand side of the road.

-Exit your vehicle and walk back toward the town.

-Ewell was wounded somewhere beyond (north of) Winebrenner’s Run.

A nice vignette from the battle and on Ewell, the Louisiana Tigers, and Henry R. Brown. Brown must have been talented to have worked his way up to staff engineer coming all the way from Tensas Parish.

I think at least part of the reason ewell wasn’t criticized as much as longstreet and stuart was because he accepted responsibility for his actions and didn’t blame others. he was exceedingly humble

The drive along East Confederate Ave. includes some of the most beautiful stretches in GNMP. I feel sorry for a wounded Richardson imprisoned on Johnson Island in Lake Erie. I live an hour east of there and know the winters can be brutal periodically.