The Wealthiest Slave in Savannah: Rachel Brownfield and the True Price of Freedom

ECW welcomes back guest author David T. Dixon

Charley Lamar was always itching for a fight. Once arrested for illegally importing slaves, he quipped that “a man of influence can do as he pleases.” Lucrative profits from blockade running led him to quit his commission as a colonel in the Confederate army and return home. Savannah, landlocked by the Union occupation of Fort Pulaski, waited fearfully for General William T. Sherman’s inexorable advance from the west. Lamar and other wealthy merchants rode out the end of the war in a city full of blacks and imprisoned Yankee soldiers. Lamar hated them all.[1]

Lamar also resented locals, blacks and poor Irish folks mostly, who shared their meager foodstuffs with the Union captives at the makeshift prison at the corner of Hall and Whitaker Streets. After all, Confederate soldiers reported that they missed many a meal in Northern prison camps. On a given evening, a passing slave could be observed hurling a loaf of bread over the stockade fence or sneaking a pail of milk through to the starving soldiers.[2]

Rachel Brownfield aroused particularly visceral emotions from Charley Lamar. Despite her status as chattel property, she parlayed her intelligence and resourcefulness into several profitable business ventures in a pre-war boom town desperate for labor and services. One evening in 1864, Lamar intercepted Rachel on a mission of mercy. The result was predictable.

Lamar did not need to ask where Rachel was going that night. Slaves and free blacks had a curfew in the city. In his view, this uppity slave woman was up to no good. Amid a hail of expletives, Lamar kicked over her bucket and scattered Rachel’s relief package in the street. He then drew his sword and threatened to run her through if he ever caught her aiding enemy soldiers again. Had Lamar known the extent of Rachel’s efforts on behalf of the Union prisoners, he might have killed her on the spot.

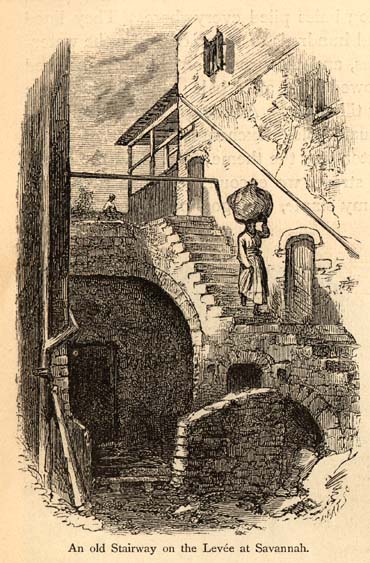

Antebellum Savannah had a vibrant black subculture, despite severe legal and social constraints. Antebellum slaves and free blacks worshiped in both black and integrated churches, ran businesses that catered to white customers and even attended clandestine schools. If there was any chance of real family life for slaves in Georgia, Savannah afforded a glimmer of hope.

As long as Rachel paid her master for her time, she could work as she pleased and he would safeguard her money in the bank.[3] Rachel leased small houses to rent in various parts of the city, took in laundry, and sold milk to feed her growing family. By the time she was sold to Savannah attorney Young J. Anderson in 1860, Rachel had accumulated several thousand dollars, most of which was held in a bank trust transferred to her new owner. When the war erupted, Rachel leased a mansion on Bryan Street from local merchant Isaac Meinhard. She paid him $10 per month and provided room and board to both white and black lodgers. The business made her wealthy.[4]

At this point in her life, Rachel Brownfield faced an important yet difficult decision. She had enough money to purchase herself and her children, but dare she attempt it? Georgia law required freed slaves to leave the state within a year of manumission, so Rachel might have to leave her mother and even her enslaved husband behind if she became free. But freedom was a fervent dream. Rachel made an agreement with Anderson in February 1863 to purchase herself and her children for $1900. She made regular payments of several hundred dollars each in gold, silver and bank bills against her emancipation debt.[5]

At this point in her life, Rachel Brownfield faced an important yet difficult decision. She had enough money to purchase herself and her children, but dare she attempt it? Georgia law required freed slaves to leave the state within a year of manumission, so Rachel might have to leave her mother and even her enslaved husband behind if she became free. But freedom was a fervent dream. Rachel made an agreement with Anderson in February 1863 to purchase herself and her children for $1900. She made regular payments of several hundred dollars each in gold, silver and bank bills against her emancipation debt.[5]

Rachel made numerous visits to the Savannah stockade. On one occasion, she was threatened by armed guards, who took the tobacco and clothing she had brought for the captives, claiming that Confederate soldiers were suffering too. Rachel then resolved to take the ultimate risk to help starving Union prisoners. She would help them escape by secreting them in her boarding house.

The house on Bryan Street boasted sixteen rooms. Black and white renters ran the gamut from slaves working their own time in the city to Confederate Naval officer Robert M. Bain. Boarders dined on fine china services and slept in rooms decorated with walnut and mahogany furniture. The secret occupants in the Brownfield boarding house enjoyed no such luxuries. Concealed during daylight hours, even their nighttime activities were strictly circumscribed. A pair of Union soldiers stayed two months before Rachel paid a local river pilot $20 in gold to transport them to Fort Pulaski. In May 1864, six more arrived. Rachel played a dangerous game of hide-and-seek with local authorities as rumors of her concealed guests swirled about town.[6]

Minehardt raised her rent to $100 per month, thinking this would force her to leave. She paid the new rate, rather than expose her secret and endanger both herself and her hidden boarders. “I did this from charity,” Rachel explained years later.[7]

In the meantime Anderson, a quartermaster in the Confederate Army, had seen his law practice dissolve and his prospects diminish. On September 24, 1864, Rachel paid him the final $550 to secure freedom for herself and her children. Anderson reneged on the deal. He demanded another $1800 or she could “go up the country and fare the same as the rest of the Negroes do.” Rachel refused, so Anderson went to the bank and withdrew her savings.

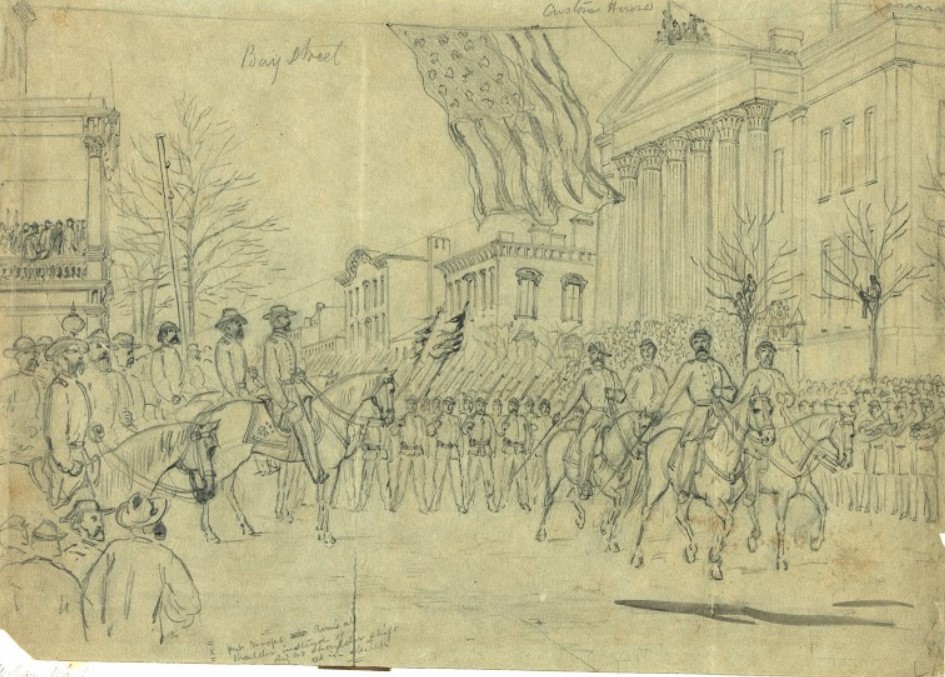

As the Union army entered Savannah, enslaved Savannah residents reacted to their deliverance with unrestrained joy. General Sherman was treated as the hero of a long-awaited jubilee. At the Brownfield boarding house, however, the celebration subsided quickly. Soldiers set up camp in the square directly in front of the residence and officers commandeered the house. For two weeks, Rachel and her daughters cooked for them while Union troops ransacked the property.

The six liberated prisoners tried to stop the pillaging, but Rachel and her boarders lost everything. Captain McIntosh said it was “a shame” the way they had treated her and promised receipts for the damages. They never materialized. Despite risking her life for such harsh rewards, Rachel insisted that she “would do it again tomorrow.”[8]

Rachel and her husband set out to rebuild their lives immediately after the war. Her former master, wounded at Cold Harbor, had died the following spring. Rachel brought suit against his estate to recover the freedom ransom.

Rachel had a strong case. Three respected white men submitted affidavits that supported Rachel’s claims. Signed receipts from Anderson detailed the payments Rachel had made to her master. Judge Thomas E. Lloyd and Freedman’s Bureau chief Lieut. J. Murray Hoag agreed that the claims were valid. Years passed with several lawyers taking the case, but Rachel never recovered her money.[9]

In the early 1870’s, Congress established the Southern Claims Commission, allowing loyal citizens in the South to recover damages caused by Union troops. Proving loyalty to the Union was easy for Rachel Brownfield. Convincing the commissioners that a slave could have held so much wealth was much more challenging. Although she applied for just the $1,659 in losses incurred at the boarding house, the commissioners allowed her only $253.70.[10]

Cancer of the uterus claimed Rachel Brownfield just a month after her fifty-first birthday in May 1884. At her death, she left her five surviving children three properties and more than $1000 in cash. The balance of her estate was left in the hands of her executor to ensure that her legacy endured.

Rachel Brownfield was proud of her accomplishments in a hard life filled with danger, disappointment, and disrespect. As a lasting symbol of her defiance to the slave-owning society that had taken so much from her, she willed that the remainder of her estate be used for the “care and adornment of my lot and gravestone” in Laurel Grove Cemetery. There she could gaze northward in perpetuity towards important white people like Charley Lamar, who were buried in a separate section. Bound together by economic necessity in life, Savannah whites insisted that they be segregated from their black neighbors after death. [11]

David Dixon is the author of The Lost Gettysburg Address. His latest book, Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General, will be published by University of Tennessee Press in September, 2020.

Sources:

[1] Charles Augustus Lafayette Lamar (1824-1865) was a wealthy slave trader and commission merchant, the son of Gazaway Bugg Lamar of Savannah. He was reputedly “the last important man killed in the Civil War,” when he was shot by Union soldiers in Columbus, Georgia. See Jacqueline Jones, Saving Savannah (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008) 100-107, 120. 126.

[2] Jones, Saving Savannah 194-197.

[3] Petition of Rachel Brownfield to recover debt, 1867, MS 603, box 2, folder 14, William Wiseham Paine Papers, Georgia Historical Society.

[4] Claim #13361, Rachel Brownfield, Southern Claims Commission (SCC). Testimony of claimant. Petition of Rachel Brownfield, William Wiseham Paine Papers.

[5] Petition of Rachel Brownfield, William Wiseham Paine Papers.

[6] Claim #13361, Rachel Brownfield, SCC. Testimony of claimant.

[7] Claim #13361, Rachel Brownfield, SCC. Testimony of claimant.

[8] Claim #13361, Rachel Brownfield, SCC. Testimony of claimant, Anne Rose Alexander, and Thomas Steward.

[9] Petition of Rachel Brownfield, William Wiseham Paine Papers.

[10] Claim #13361, Rachel Brownfield, SCC. Approved claim receipts.

[11] Chatham County Deeds 3Z:298, 4W:389, 6X:371, 6X:373. Chatham County Wills: O:414. Savannah Georgia Vital records 1803-1966, accessed at Ancestry.com. 1880 Federal Census, Savannah, Chatham, Georgia; Roll: 138; Family History Film: 1254138; Page: 599C; Enumeration District: 030; Image: 0761

What a great story!

Thanks Matt. A pdf of the longer print version of this story may be downloaded free on my website http://www.davidtdixon.com.

Very interesting! I travel to Savannah frequently and am very familiar with the city’s rich history, but i did not know the story of Rachel Brownfield.

Does her house still stand, and which square was it located on?

The 18th century house was converted to a duplex in the twentieth century and sits facing Warren Square at 324/326 East Bryan Street.

An untold tale, until now.

Thanks Pat. This is the digital debut of a longer piece originally published in Georgia Backroads magazine.

Excellent article. Always good to read stories like this.

Thanks Eric. Glad you enjoyed it.

Great story! Thanks!

Thanks so much. The topic of Irish Confederates is only briefly alluded to in my article. They deserve more attention. I was surprised that Rachel’s former master, and Irish immigrant who had “shared” her and her mother as property with various white men, presumably for the purpose of breeding more slaves, came out so strongly for her in the trial. I am eager to learn more about this dynamic, especially since the catholic Church in Savannah was apparently supportive of free Blacks and enslaved people, allowing them to marry, attend churches with whites, and baptized their children.

David, I’ve recently found out I’m a descendant of Rachel’s. What do you know of her daughter, Margaret? I loved the article.

Thank you, Sharon

Sharon please send me an email at davedixonhistory@gmail.com and we can exchange info. Thanks