The Army of the Potomac’s March from Harrison’s Landing

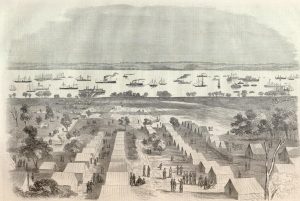

On August 14, 1862, the Army of the Potomac began departing its safe haven of the last month: its camp at Harrison’s Landing on the James River. George B. McClellan’s army lost nearly 16,000 men in late June and early July during the Seven Days’ Campaign. Now, under orders of General-in-Chief Henry Halleck, McClellan’s plans to capture Richmond officially ended.

For the common soldiers of the Army of the Potomac, leaving Harrison’s Landing was a blessing. The historian of the 2nd New York Infantry described the ordeal as follows:

The occupation of this point [Harrison’s Landing] had been a terrible experience for the army, and the Troy regiment suffered with the rest. The excessive heat, bad water, poor food, constant exposure and lack of rest or recreation, added to the disgusting experiences at Fair Oaks, had rendered many of the men useless as soldiers, having caused a large number of chronic disease. No less than 108 members of the regiment, who but a short time before had been in perfect health, were transported to hospitals, the majority of them finally being discharged for disability.

Heat plagued the soldiers in their encampments and it troubled the Federal soldiers as they marched towards their transports waiting to be fully loaded before steaming towards Washington and Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia. The dry roads on the Virginia Peninsula choked the soldiers with dust as they marched. “Our march was most fatiguing,” said Lt. Col. Franklin Sawyer of the 8th Ohio Infantry. “The dust along the road was pulverized to the fineness of extra superior flour, and we soon looked more like an army of millers than soldiers in blue.”

The Civil War had changed dramatically from the time of the army’s arrival on the Peninsula to the time of its departure. Congress passed two confiscation acts and began implementing a harder war policy on the Confederacy. Privately, Abraham Lincoln had already announced to his Cabinet his intention to emancipate the South’s slaves. These heightened stakes were not on the table earlier in 1862 but McClellan’s failure to capture Richmond prompted a change in the Union war effort. The Army of the Potomac’s march from Harrison’s Landing down the Peninsula reflected the army’s–and the nation’s–changing attitudes towards their Southern brethren.

A New York Tribune correspondent embedded with the army recorded the soldiers’ aggressive foraging habits during their retrograde march:

Foraging for anything and everything edible has been the most interesting item of the march. The corn-fields, just arrived at roasting adolescence, have been systematically stripped for a mile either side of the roads marched over. Every farm-house in sight was visited by a continual stream of out-of-their-ranks solders. Eggs and poultry first disappeared, then pigs and calves. Horses and mules were pressed into the transportation of soldiers, who, turning them loose after a few miles, would not get out of view before others had mounted them. In every kitchen you would find a crowd hurrying up the manufacture of doecakes by the servants, or themselves boldly venturing upon the mysteries of cookery. They climbed for fruit, ripe and green; they dug potatoes; they munched cabbage; they milked cows.

The foraging was so extensive that the correspondent concluded, “I do not see how the people left in the country are to avoid starvation. I doubt if there remains a cock to crow to-morrow morning on all the route between here and Harrison’s Landing.”

Food and animals were not the only items to accompany the Army of the Potomac on its march. The same correspondent said, “Moreover, the negroes of the whole region join the army in its march. They were contented to remain at the old homesteads while we were between them and their masters, but now that we depart they are too sharp to expect to see those white runaways in peace, and prefer not to see them at all.”

Overall, the march from Harrison’s Landing taxed the army. “In consequence of the length of the march and the dry state of the ground, causing a continual dust, combined with great scarcity of water and the crowded condition of the ship, the men were very much exhausted, and not in a suitable condition for immediate active service,” reported Capt. George Hoffman of the 8th New Jersey Infantry.

Though officers claimed their men were not in “condition for immediate active service,” future marches and battlefields awaited the army in Northern Virginia and, ultimately, in Maryland.

Dr. Abner Hard, Surgeon for the Eighth Illinois Cavalry, writes about the evacuation and hospital set up at Harrison’s Landing in his history of the regiment. https://books.google.com/books/about/History_of_the_Eighth_Cavalry_Regiment_I.html?id=dbQdAQAAMAAJ