Book Review: A Fool’s Errand. By One of the Fools: A Novel of the South During Reconstruction

For historians, reading is a full-time job. Nothing is too insignificant not to read, from cereal boxes to torn bits of paper with evidence of pencil scratches. Reading books popular during a specific period of the past is an excellent way to gain insight into the minds of the folks who read them first. Old novels like So Red the Rose, A Lincoln Conscript, or Uncle Tom’s Cabin are treasure chests of social and political information. Macaria: or Altars of Sacrifice, by Augusta Jane Evans, not only helps place women realistically within the confines of war, but Evans based her description of First Bull Run (or First Manassas) on her extensive interview with General P. G. T. Beauregard. The verses of Edgar Allen Poe and the paragraphs of Sir Walter Scott, although written earlier, were still influential to southern culture. “Reading what they read,” is not an unworthy goal for any historian.

For historians, reading is a full-time job. Nothing is too insignificant not to read, from cereal boxes to torn bits of paper with evidence of pencil scratches. Reading books popular during a specific period of the past is an excellent way to gain insight into the minds of the folks who read them first. Old novels like So Red the Rose, A Lincoln Conscript, or Uncle Tom’s Cabin are treasure chests of social and political information. Macaria: or Altars of Sacrifice, by Augusta Jane Evans, not only helps place women realistically within the confines of war, but Evans based her description of First Bull Run (or First Manassas) on her extensive interview with General P. G. T. Beauregard. The verses of Edgar Allen Poe and the paragraphs of Sir Walter Scott, although written earlier, were still influential to southern culture. “Reading what they read,” is not an unworthy goal for any historian.

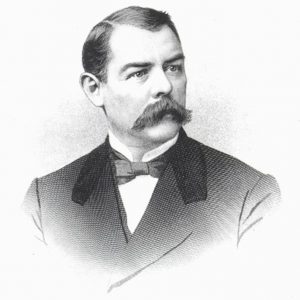

As one reads modern books analyzing Reconstruction by historians such as Alan Guelzo, Eric Foner, and Brooks Simpson, the name of one other author often pops up: Albion Tourgee. His novel, A Fool’s Errand, is mentioned as having a unique point of view due to having been published in 1879, during actual Reconstruction. Albion Tourgee has some pretty impeccable credentials to back up his effort, although the book was initially published anonymously. Nevertheless, it was an immediate hit nationwide, selling over 200,000 copies.

As a Union soldier, Tourgee sustained wounds at the First Battle of Bull Run and the Battle of Perryville. He was also a Radical Republican, lawyer, politician, and sometimes diplomat. Returning home, he served as the lead attorney for Homer Plessy in the landmark case Plessy v. Ferguson, cementing his progressive as well as intellectual credentials. In 1897 President William McKinley appointed him U.S. consul to France, where he served until his death in 1905.

To write A Fool’s Errand, Tourgee drew on his own experiences in the Deep South after the Civil War. Today, readers understand expressions like “carpetbagger” and “scalawag” as specific individuals who did particular things. A carpetbagger was a person from the Northern states who came South after the war to exploit the local populace for financial profit; a scalawag was a local white Southerner who collaborated with Northern Republicans after the war, again for profit. Tourgee puts faces and personalities behind these words. Yesterday’s carpetbagger would be today’s entrepreneur.

So often, the North bears the blame for the failure of Reconstruction. A Fool’s Errand clearly illustrates the complexity of the issue. Many former Union soldiers came back to the southern states, having preferred the warm climate to colder northern temperatures. Others saw an economic opportunity after the war perhaps denied them had they remained “at home.” Rather than welcoming an infusion of income and energy, these northern investors experienced almost universal vilification. The South did not care to be “reconstructed” by well-meaning individuals, corporate investors, or the federal government. Tourgee’s book offers a clear illustration of this issue. The blame belongs to the South. Southern unwillingness to admit their loss and move forward, welcoming northern help, made fools of many.

The main character, Comfort Servosse, is a Union officer who served in the South. While there, he was so impressed with the potential the area offered to not only make money but to be part of the creation of a new, more equitable civilization. Servosse and his family come South with no hidden agenda. They want to make a decent living in a pleasant place. It was not to be. The troubles that they encounter are the kind that makes or breaks a family, and by the end, shambles ensue. In Comfort’s words, “We tried to superimpose the civilization, the idea of the North, upon the South at a moment’s warning … it was a fool’s errand.” Much later, Tourgee claimed Reconstruction was a failure “so far as it attempted to unify the nation, to make one people in fact of what had been one only in name before the convulsion of Civil War. It was a failure, too, so far as it attempted to fix and secure the position and rights of the colored race.”

Albion Tourgee’s writing style is one of the most compelling reasons to read this excellent book. He is a terrific writer. There is a distinct elegance to good nineteenth-century writing that uses language like a rapier, not a club. The San Francisco Chronicle said, “Its word-pictures are so realistic that one sees, hears, and feels the very presence of the individuals that crowd its pages.” A Fool’s Errand reads as easily now as it did in 1879. With its commentary on racial issues in the American South, it continues to be essential reading for citizens of the twenty-first century (and Civil War fans) as it was for those of the nineteenth. Check out the offerings from the online booksellers and try this one out yourself.

Albion Tourgee’s writing style is one of the most compelling reasons to read this excellent book. He is a terrific writer. There is a distinct elegance to good nineteenth-century writing that uses language like a rapier, not a club. The San Francisco Chronicle said, “Its word-pictures are so realistic that one sees, hears, and feels the very presence of the individuals that crowd its pages.” A Fool’s Errand reads as easily now as it did in 1879. With its commentary on racial issues in the American South, it continues to be essential reading for citizens of the twenty-first century (and Civil War fans) as it was for those of the nineteenth. Check out the offerings from the online booksellers and try this one out yourself.

Albion Tourbee, A Fool’s Errand. By One of the Fools: A Novel of the South During Reconstruction

Fords, Howard & Hulbert, 1879

328 Pages

(This review was previously published In Civil War News, 2016)