Joe and the Illini: The Unclear Origins of Two “Fighting” Nicknames

Every few years my alma mater, the University of Illinois, renews the discussion of renaming its sports teams and creating a new mascot. In 2007 the school retired Chief Illiniwek and the trademarked Chief logo in an attempt to distance itself from connections with Native American imagery. Several weeks ago, the student senate recommended retaining the Fighting Illini nickname while adopting the belted kingfisher as a new mascot. The ensuing discussion demonstrated the ongoing lack of clarity behind the origins of the school’s use of both Illini and Fighting Illini as nicknames.

My own recent research has revealed that the “Fighting” sobriquet may have originated from an excited newspaperman, similar to the famous story behind the “Fighting Joe” Hooker nickname. However, further digging into those Civil War sources shows that the popular consensus among historians might be mistaken. Joseph Hooker ably led a 3rd Corps division during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign and Seven Days Battles. After one of those engagements—traditional sources point to both Williamsburg and Malvern Hill—a newspaper supposedly printed Fighting Joe by mistake. Despite Hooker’s later objections to its connotations, the nickname stuck. Unfortunately, I cannot seem to find an actual 1862 source that says the same story.

It is lazy historical writing to just stack multi-paragraph blockquotes from primary sources, but since this is a story about the creation of a myth, it is important to track the evolution with minimal interpretive interjection. The earliest instance that I located of the traditional Fighting Joe creation, as popularly believed, comes from late-January 1863, when the New York Herald announced Hooker’s assumption of command of the Army of the Potomac. The Herald stated:

“On one occasion, after a battle, in which General Hooker’s men had distinguished themselves for their fighting qualities—thus adding to the fame of their commander—a despatch to the New York Associated Press was received at the office of one of the principal agencies announcing the fact. One of the copyists, wishing to show in an emphatic manner that this commander was really a fighting man, placed over the head of the manifold copies of the despatch the words ‘Fighting Joe Hooker.’ Of course this heading went to nearly every newspaper office of the country, through the various agencies, and was readily adopted by the editors and printed in their journals. The sobriquet was also adopted by the army and by the press, and is now well known all over the world. Thus an unpretending, innocent copyist, unaware that he was making history, prefixed to this General’s name a title that will live forever in the annals of the country.”[1]

Similar renditions continued to anonymously appear. The October 1865 issue of Harper’s Magazine explained:

“The agent of the New York Associated Press is often compelled, during exciting times, to furnish his telegraphic accounts by piecemeals, in order to enable the papers to lay the facts before the public as fast as possible; and hence, in order to number the pages correctly, he has to originate what are called ‘running heads,’ each being repeated with every page. It was common for instance, during the trial of the conspirators at Washington, to number the pages: ‘Assassins, 1;’ ‘Assassins, 2’ etc.; and during the removal of the President’s body to Springfield the running headlines was: ‘the Funeral, 1;’ ‘the Funeral, 2,’ etc.

“When the account of the battle of Malvern Hill was being received by the Associated Press, there was such great excitement in the city that it even extended to the telegraph operators and copyists, who were generally proof against such fevers of excitement. In the midst of the sensation which that battle created, one of the copyists, in his admiration of the gallantry and daring of General Hooker as detailed in the report, improvised a ‘running head,’ ‘Fighting Joe Hooker,’ which was repeated page after page. Two or three of the papers adopted it as the head-line for the printed accounts, and heralded the battle under that name. The name ‘stuck,’ and has been fixed on Hooker irretrievably.”[2]

Brooklyn attorney Sidney V. Lowell claimed responsibility in 1903 for the newspaper blunder that produced the nickname, writing:

“I well remember an occasion when I was in position to help make a great man’s reputation. I was reading proof on the New York Courier and Enquirer, and had been at work from seven o’clock in the evening until three in the following morning. McClellan had come into contact with the Confederate forces and was pressing them back toward Richmond. Our press despatches from the front, written with carbon on manifold sheets of tissue paper, told of desperate fighting all along the McClellan’s line. Among his corps commanders was General Hooker, whose command had been perhaps too gravely engaged. Just as the last page forms of the Courier and Enquirer was made ready for the press another dispatch came in from the front giving further particulars of the fighting in which Hooker’s corps was so desperately engaged, and across the top of the dispatch was written ‘Fighting—Joe Hooker.’ I knew that this line meant that the matter should be added to what had gone before, but the compositor who put it in type knew nothing about the preceding matter, consequently he set the phrase as a headline, ‘Fighting Joe Hooker.’ Concluding that it made a good headline, I let it go. I realized that if a few other proof readers treated the phrase as I did, Hooker would live and die as ‘Fighting Joe Hooker.’ Enough additional proof readers acted likewise to do the business.”[3]

Chancellorsville historian John Bigelow reprinted Lowell’s letter in his massive study on that campaign and it is commonly accepted as the genesis of the “Fighting Joe” nickname.[4]

However, Hooker’s biographer Walter Hebert challenged the popular tale, writing in 1944:

“This account of the derivation of his nickname has been the accepted story, and it is supported by a wealth of detail concerning the incident, but it is still not altogether satisfactory. The typesetter involved purportedly worked for the New York Courier and Enquirer, but by 1862 this paper had been swallowed up by the New York World. The sobriquet does not appear in any issue of the World immediately after the battle of Williamsburg or any other battle on the Peninsula. The same is true of all other papers of that period which the author has been able to examine. ‘Fighting Joe’ does not appear in common usage for four months after Williamsburg. A reasonable conclusion is that in some spontaneous manner it was applied to Hooker after Williamsburg and was revived popularly as his aggressive leadership guided his command into one desperate fight after another.”[5]

Just like Hebert, I have been unable to locate anything published during the spring and summer of 1862 resembling the rumored “Fighting Joe Hooker” headline. Even the advantages of keyword searchable online newspaper databases have not enabled me, or any other Civil War researchers of which I am aware, to prove Lowell’s claim.

The first instance I can find of the nickname’s use is from a correspondent of the 1st Massachusetts Infantry writing to the Boston Morning Journal in mid-June 1862:

“Since the battles of Williamsburg and ‘Seven Pines,’ the boys call Gen. Hooker ‘Fighting Joe.’ At the battle of Williamsburg he risked his life in a desperate way at the right moment. When we were outnumbered, worn out and badly cut up, he rode down the lines in the very face of the enemy. Two horses were shot under him, but he brought the men straight up to the mark and was unhurt. The cry was, ‘Hooker says we must hold on.’ The men might have been killed off, but they could not be driven beyond a certain position he planted them on.”[6]

Around the same time Chaplain Arthur B. Fuller of the 16th Massachusetts Infantry wrote, “This division (Hooker’s) is emphatically a fighting division, its General being familiarly termed ‘Fighting Joe Hooker,’ and is abundantly dreaded by the enemy.”[7] Several days later Fuller wrote, “Gen. Hooker is usually termed ‘fighting Joe Hooker,’ and has been conspicuous for good Generalship and determined courage all through this contest.”[8] The chaplain brought up the nickname again at the end of the month. “Gen. Hooker, called ‘Fighting Joe,’ is second to none in courage or military strategy.”[9] Thus we already find consistent, affectionate use of the nickname among the soldiers in Hooker’s division during June 1862. This usage predates any headline typos.

The “Fighting Joe” story typically attributes a New York newspaper as the basis, and the earliest instance I can find in those comes from a correspondent of the New York Herald. He noted in a July 13 letter that Union soldiers had already popularized the “Fighting Joe” nickname.[10] Several weeks afterward the paper further elaborated:

“It is a remarkable fact how the gallant troops under General Hooker doat on their leader. His great daring, coolness under fire and humane treatment in camp have endeared him to the hearts of his followers, and the fighting qualities of the General have earned for him the sobriquet of ‘Fighting Joe.’”[11]

Hooker’s performance in the 1862 Maryland Campaign inspired the first widespread use of the nickname, still in a positive light. Only after President Lincoln selected Hooker to command the Army of the Potomac in January 1863 did newspapers begin printing the familiar “Fighting Joe” origin stories. Hooker’s ensuing failures at Chancellorsville caused reporters to mockingly use the moniker, and most public historians still apply it in a similar fashion. Many soldiers who Hooker directly led, however, continued to affectionally use the nickname for their commander, even in their postwar recollections. For Hooker’s part, he disliked the phrase, supposedly stating, “Don’t call me Fighting Joe, for that name has done and is doing me incalculable injury. It makes a portion of the public think that I am a hot headed, furious young fellow, accustomed to making furious and needless dashes at the enemy.”[12]

By modifying the creation story of “Fighting Joe,” therefore, we are not performing revisionist history to tear down a historical figure’s legacy. Rather, we should rightfully acknowledge that the original bestowing of Hooker’s nickname did indeed reflect the admiration of his men. In this case the peculiar story does not hold up to the historical record. In the case of the Illini nickname, meanwhile, I have found a use of “Fighting” that reveals an evolutionary story more complete than the popularly known version.

As I am less familiar with the sources available for the University of Illinois and its athletic programs than I am for Civil War research, I think it necessary to specify my methodology for my investigation into the Fighting Illini nickname. I relied upon historic newspaper databases, the student yearbook Illio, and The Alumni Quarterly and Fortnightly Notes. It is entirely possible that Illini or Fighting Illini may have been used in different manners and in earlier years than what I have found. However, I am satisfied that the University of Illinois Archives employed a similar approach for their own “Fighting Illini” FAQ and has not been able to highlight earlier use than my own research. Nevertheless, as my limited research discovered source material that predates those upon which the university archives based their conclusions, I must therefore acknowledge that further digging into the subject could likewise make my own observations obsolete.

The University of Illinois was founded at Urbana-Champaign in 1867 as the Illinois Industrial University. One of the original public land-grant institutions established by the 1862 Morrill Act, the college directly owed its existence to the Civil War absence of southern congressmen who, if they acted according to their own precedents, would have opposed the legislation. “The second session of the 37th Congress (1861-62) was one of the most productive in American history,” noted James McPherson.

“Not only did the legislators revolutionize the country’s tax and monetary structures and take several steps toward the abolition of slavery, they also enacted laws of far-reaching importance for the disposition of public lands, the future of higher education, and the building of transcontinental railroads. These achievements were all the more remarkable because they occurred in the midst of an all-consuming preoccupation of the war. Yet it was the war—or rather the absence of southerners from Congress—that made possible the passage of these Hamiltonian-Whig-Republican measures for government promotion of socioeconomic development… The success of the land-grant college movement was attested by the development of first-class institutions in many states and world famous universities at Ithaca, Urbana, Madison, Minneapolis, and Berkeley.”[13]

The university archives claimed, “The earliest recorded usage of the term ‘Illini’ appears to have been in January 1874,” but it is unclear if they specifically meant the use of the term in reference to the school.[14] It certainly was in use before then, often mixed interchangeably with Illiniwek, Illinois Indians, and Illinois Confederation to describe about a dozen tribes, including the Cahokia, Peoria, and Kaskaskia, who inhabited the land that eventually became the state of Illinois.

Missionary Louis Hennepin accompanied Robert La Salle’s expedition to New France in 1675 and explored all the way to the Mississippi River. After returning to Europe he published several books about his journey. The 1698 English version of A New Discovery of a Vast Country in America is the earliest publication where I find the term Illini: “This word Illinois, comes, it has been already observed, from Illini, which in the language of that nation signifies A perfect and accomplished Man.”[15]

An October 1873 issue of the Alton Telegraph contained an article summarizing the history of the state. It stated, “The name of Illinois is from the Illini tribe of Indians, who lived along the Illinois river, and gave their name to that stream and the whole northern section of the State. The name, Illini, means ‘real men,’ or superior way.” The Student, a weekly newspaper published by University of Illinois students, immediately republished the article.[16] On the first day of the following year, The Student renamed itself The Illini. The editors noted that the term derived from the word Illinois but suggested they had invented it themselves, even offering a pronunciation guide as if it was entirely new, and the university archives still rewards them with the creation despite noted earlier use.[17]

Nineteenth century recaps of athletic competitions referred to Illinois teams simply as “Varsity,” “U of I,” “Champaign,” and “The University of Illinois Football Team.” The “Indians” nickname also saw widespread popularity prior to any usage of Fighting Illini or Chief Illiniwek. Clad in various outfits during the early years, the school resolved its official colors in 1894 and for several decades sports stories frequently referred to the team as the “Orange and Blues.”

The nickname Illini started to appear more frequently in the early twentieth century, as did Native American associations. The Daily Illini referred to the football team as the “Illini” as early as the 1901 football season, noting in a 27-0 victory over Iowa, “The splendid endurance of ‘Illini’ began to tell.”[18] A local Champaign newspaper also used Illini that winter in a story about the upcoming baseball schedule.[19] The Illio yearbook likewise frequently used Illini in an article discussing that team’s barnburner trip out east to play Ivy League schools.[20] The same yearbook also summarized a football game from October 10, 1903: “The Illini warriors skin eleven Rush Medical doctors. Score, 64 to 0.”[21]

The first possible instances of “fighting” Illini referred to the 1910 undefeated Big Ten champion baseball team. The Decatur Herald described a game against Purdue on May 10 that year, where, after falling behind 4-0 in the second inning, the “Illini, fighting mad, came back in the third and fifth innings and tied the score, then squeezed the winning run over in the sixth.”[22]

Ten days later, the Illini beat the rival University of Chicago Maroons in a 17-inning affair. “Time and again Chicago apparently had the game all but won, but the fighting Illini came back grittier than ever,” reported the Decatur Herald. Between 8-10,000 fans attended the game. The same article noted, “The crowd of spectators was one of the greatest ever on Illinois field.”[23]

It thus stands to reason that a pair of memorable games, reports of which both noted the “fighting” caliber of the Illinois team and the latter drawing a significantly larger crowd than normal, may have influenced creation of the “fighting” Illini nickname. This perhaps is overly speculative, but the Daily Illini indeed began using the term the following basketball season. Any of my fellow perpetually grumpy Illini basketball fans can cynically commiserate that this first “fighting” usage was done in a disparaging way to describe losing a lead in a 33-29 defeat to Purdue. Illinois had begun the game on a roll, “Then Purdue got started, and it was see-saw, until just before the end of the half, when the Boilermakers drew away from the vainly fighting Illini.”[24] Newspapers continued to sporadically attach the “fighting” description to Illini sports teams throughout the decade. Even the University of Michigan student newspaper used the moniker in 1916 to describe an unexpected Illinois win over Minnesota.[25]

The nickname found new meaning in 1917 with the entry of the United States into World War I. Nearly 9,500 faculty, staff, and students served in the armed forces during the war.[26] Articles about their mobilization and service referred to them as “Fighting Illini” and the student newspaper frequently published their correspondence under the headline “A Line or Two from Fighting Illini.” Ultimately 183 Illinois students lost their lives in the conflict, including several athletes.

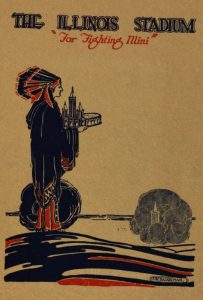

In 1921, athletic director George Huff and football coach Robert Zuppke proposed a new stadium to honor those who died. The final design included an iconic column for each fallen student. Professor C.H. Woolbert, of the public speaking division, suggested the slogan, “Build That Stadium for Fighting Illini.” Zuppke approved the message, noting, “This is a full, round, imperative statement. It does not sound like a saxophone, but like a fife and drum. The word ‘fighting’ carries the idea of memory for the boys who went across, the spirit of our games and the men and women who come to see them.”[27]

Coach Zuppke fervently championed the cause, embarking on a fundraising circuit throughout the summer of 1921. “The Stadium should stand as the dignified expression of the ideal of service,” he wrote in a promotional booklet, The Illinois Stadium: “For Fighting Illini.”

“It should rise above our state prairies as a fitting Memorial for the Illinois men and women who served and fought and died in the service of our country in the great World War. It should be a token of our gratitude to them; to the men on the athletic teams and debate teams who have made the name of Illinois famous; to the notable men and women who have borne the burden of leadership throughout this state and others after they have received their training here. It should be an inspiration to all the people of the state.”[28]

The study of history involves looking at both trends and moments. While the meaning and motives behind Fighting Illini are still up for debate, I am convinced that November 19, 1921 was the day that the Illinois football team thereafter became the Fighting Illini.

Zuppke’s squad claimed the fighting nickname for themselves that fall despite an underwhelming season where they did not score a single touchdown in conference play until the final game. “It was one of fate’s ironies that somebody had to dub them ‘Fighting Illini’ the very season the fight turned out to be a losing one,” noted the Decatur Herald as the university worried about the impact a poor season might have on fundraising for Memorial Stadium.[29] The Illini entered their last game at Ohio State as a heavy road underdog. Should they have limped across the finish line that year it is possible that growing enthusiasm for the new nickname association may have deflated.

College football in the 1920s did not have 85 scholarship rosters, spread offenses, and third down nickel packages. They still typically rotated players. Zuppke, however, challenged eleven of his team to play the entire Ohio State game without substitution. They responded with a hard-fought 7-0 victory. “If ever a football team deserved its nickname stressed and reiterated as a real courage bringer during a disastrous season, it was those young men from Urbana who fully earned their objective on Ohio field this afternoon,” praised the Chicago Tribune.[30] The Alumni Quarterly & Fortnightly Notes beamed, “Zuppke’s fighting Illini beat Ohio State!” in their December 1 issue and proudly promoted the nickname’s appropriateness for aspects of the university:

“Never before has the word fight enjoyed more popularity with Illini everywhere. The stadium slogan, Build That Stadium For Fighting Illini, has of course woven the word into Illinois tradition as nothing else could; and the song ‘Fight Illini,’ is catching on. We have a ‘Fight Illini’ yell, and the football critics are beginning to call us the fighting Illini, as the Center collegians are called the ‘praying colonels,’ and Notre Dame the fighting ‘Irish.’

“Illinois has had one fight after another to get what she has today. Every building on the campus has come only after a fight for it. We have to fight for appropriations, for faculty men, for library books, for everything we have and are.”[31]

At the end of season banquet, athletic director George Huff declared, “Whatever the defeats of the season may have been, this year’s team has fixed the name ‘Fighting Illini’ on Illinois football.”[32]

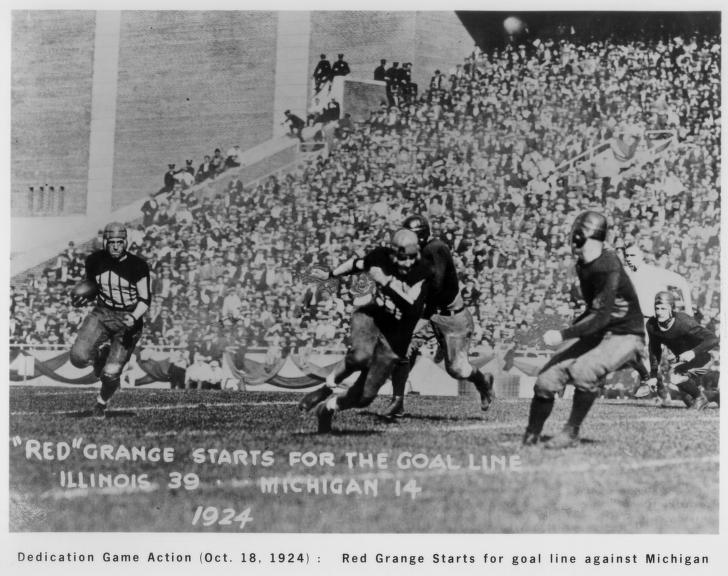

At the time the stadium fund had raised $1.5 million. Construction of Memorial Stadium concluded two years later during a 1923 season in which the 8-0 football team were deemed co-national champions. This was also the first season for legendary running back Red Grange. Frequently ranked among the greatest college players of all time, the “Galloping Ghost” christened the stadium on the day of its formal dedication, October 18, 1924. After returning the opening kickoff to the house, Grange rushed for over 400 yards and four touchdowns, and contributed another score through the air. Nationwide recaps of the iconic game abundantly utilized “Fighting Illini.”

We can therefore identify a timeline for the growth of the Fighting Illini nickname. What may have begun with a couple baseball articles in 1910 sensationalizing a pair of dramatic games slightly grew in use for seven years until World War I challenged the students to demonstrate their fight on the battlefield and home front. The university connected the service and sacrifice of its students to a Memorial Stadium for Fighting Illini and Zuppke’s upset victory against a conference rival during the first year of stadium fundraising gave legitimacy to the name for the football team. Finally, on the day of the new stadium’s official dedication, Red Grange cemented the connection with the most impressive game of his distinguished college career.

You could thus conclude the story of how University of Illinois sports teams became the Fighting Illini during the early twentieth century, but it would be disingenuous to only connect the nickname with the memory of Illinois soldiers and the spirit of its athletes.

Native American imagery and symbolism frequently appeared throughout the decade-and-a half of the nickname’s rise in popularity. An illustration of a chief presenting the stadium as a gift to the school appeared on the cover of The Illinois Stadium, and another souvenir picture book by Clarence Welsh stated, “The Stadium will become the symbol of a new, united, fighting, aspiring tribe of Illini, who know how to honor their living heroes and venerate their dead.”[33] Zuppke made similar connections as he raised funds for Memorial Stadium’s construction. “Illini is part of the word Illiniwek, which means the complete man,” he explained, “and we want a Stadium which will represent the complete man.”[34]

“An Indian tribe began it a long time ago,” began another 1921 booklet telling The Story of the Stadium. “[W]e have a heritage from them,” it explained while attempting to connect the story of the Illinois tribes with that of the stadium. “See us today living vitally in our heritage. Watch us play football; see us on the cinder track, on the baseball diamond… We are different somehow, we of the middle west—not particularly better, but different. We are uniquely ourselves.”[35]

Articles about Illinois sports heavily used Native symbolism. The November 20, 1921 Daily Illini headlined a cross country victory as “Indians Get Conference Track Scalps” as it devoted much of the same issue to Zuppke’s football win over Ohio State. Among many allusions to Native imagery was the story of the reaction on campus. “While 3,000 ecstatic Indians rushed into the muddy warpath at Columbus, twice as many seethed in the victory dance through the Champaign streets.”[36] (Allow me to add here that, from what I can remember, the upset of #1 Ohio State by Ron Zook’s football team and the resulting celebration was among my favorite memories from college.)

In 1926, two students introduced Chief Illiniwek to a packed Memorial Stadium. This symbolic representation, entirely by white students except for one year during World War II, continued through 2007. Chief Illiniwek dominated popular associations with the Fighting Illini and led to uncertainty even about the origin of the nickname itself.

Should University of Illinois sports teams continue to have no mascot and our logos remain a simple “Block I,” the story behind the Fighting Illini nickname is organic and unique, even if the full details are still unresolved. Excitingly, there is still more research left. I’m particularly glad that the genesis of the school nickname is evolutionary over the course of several decades and not just a simple poll for one class of students to choose between Wildcats, Bulldogs, or Eagles. It is a tradition that ought to generate pride both for the Illinois soldiers for whom Memorial Stadium was dedicated and for the pluck of the Illini sports teams who first attained that fighting attribute. As with “Fighting Joe” Hooker, we can find the original commendable intentions when we dismiss the popular version and investigate the actual primary source documentation.

Sources:

[1] “The New Commander of the Army of the Potomac,” New York Herald, January 27, 1863.

[2] “Fighting Joe Hooker,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Volume 31 (New York: Harper and Brothers, October 1865), 644.

[3] Army and Navy Journal, Volume 40, Number 50 (New York: Army and Navy Journal Incorporated, August 15, 1903), 1256.

[4] John Bigelow Jr., The Campaign of Chancellorsville: A Strategic and Tactical Study, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1910), 6.

[5] Walter H. Hebert, Fighting Joe Hooker (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1944), 91.

[6] “Correction,” Boston Morning Journal, June 17, 1862.

[7] A.B.F. to “Editor of the Boston Journal,” June 14, 1862, “Our Army Correspondence,” Boston Morning Journal, June 19, 1862.

[8] A.B.F. correspondence, June 17, 1862, “Letter from the Army Before Richmond,” Boston Traveler, June 21, 1862.

[9] “A.B.F. correspondence, June 22, 1862, “From the Army of the Potomac,” Boston Traveler, June 27, 1862.

[10] “Our Army Correspondence,” New York Herald, July 17, 1862.

[11] “Our Army Correspondence,” New York Herald, August 1, 1862.

[12] “The New Commander of the Army of the Potomac,” New York Herald, January 27, 1863.

[13] James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 450-451.

[14] “Fighting Illini FAQ,” https://archives.library.illinois.edu/features/illini.php.

[15] L. Hennepin, A New Discovery of a Cast Country in America (London: M. Bentley & J. Tonson, 1698), 95.

[16] “Something Concerning the Ancient History of Illinois,” The Student, November 1, 1873,

[17] “Editorial,” The Illini, January 1, 1874, 26.

[18] “‘Varsity Vindicated,” Daily Illini, November 11, 1901.

[19] “Managers Could Not Agree,” Champaign Daily News, January 11, 1902.

[20] The 1904 Illio (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois, 1904), 306-308.

[21] The 1905 Illio (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois, 1905), 406.

[22] “Purdue Threatens Illinois’ Position,” Decatur Herald, May 11, 1910.

[23] “Great Day for IIllinois Men,” Decatur Herald, May 21, 1910.

[24] “Illini Fall Before Boilermakers 33 to 29,” Daily Illini, January 29, 1911.

[25] “This Week Places Conference Title,” The Michigan Daily, November 24, 1916.

[26] Mike Pearson, “Illini Trials, Tribulations and Triumphs,” May 30, 2020, https://fightingillini.com/news/2020/3/29/general-illini-trials-tribulations-and-triumphs.

[27] “Prof. Woolbert’s Slogan Picked To Call Illini to Build Stadium,” Daily Illini, March 16, 1921.

[28] The Illinois Stadium: “For Fighting Illini” (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois, 1921), 11.

[29] Decatur Herald, October 30, 1921.

[30] Harvey Woodruff, “Ohio vs. Illinois,” Chicago Tribune, November 20, 1921.

[31] Harvey Woodruff, “Football Season ends in Glory as Fighting Illini Win from Ohio State, 7-0,” The Alumni Quarterly & Fortnightly Notes, Volume 7, Number 5, December 1, 1921, 53-54.

[32] “Varsity Elects Don Peden as Pilot for 1922,” Daily Illini, November 22, 1921.

[33] Clarence Welsh, University of Illinois Memorial Stadium (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois, 1921), 39.

[34] “Stadium Mass Meet Explains County Duties,” Daily Illini, April 1, 1921.

[35] The Story of the Stadium (Urbana IL: University of Illinois, 1921), 1.

[36] Daily Illini, November 20, 1921.

Them’s fightin’ words!

“Oskee Wow-Wow Illinois!” When I was in grad school at the Big U, the “Campus Scout” humor column in the student newspaper claimed that was Indian-talk for “beat their heads in.”

America is in a “little Red Book” moment of sorts. I suspect Illinois will return to being the Fighting Illini one day soon. Our college educated governing class is being found to be wanting morally and intellectually.

How about in a newspaper article describing a portion of the Seven Day’s campaign, a typesetter left out the second comma in the sentence, “in the center of his division, fighting, Joe Hooker was directing every aspect of the battle.”