The 1858 New Orleans Mayoral Election

This article was co-written with Michael Kraemer, a PhD student at The Ohio State University

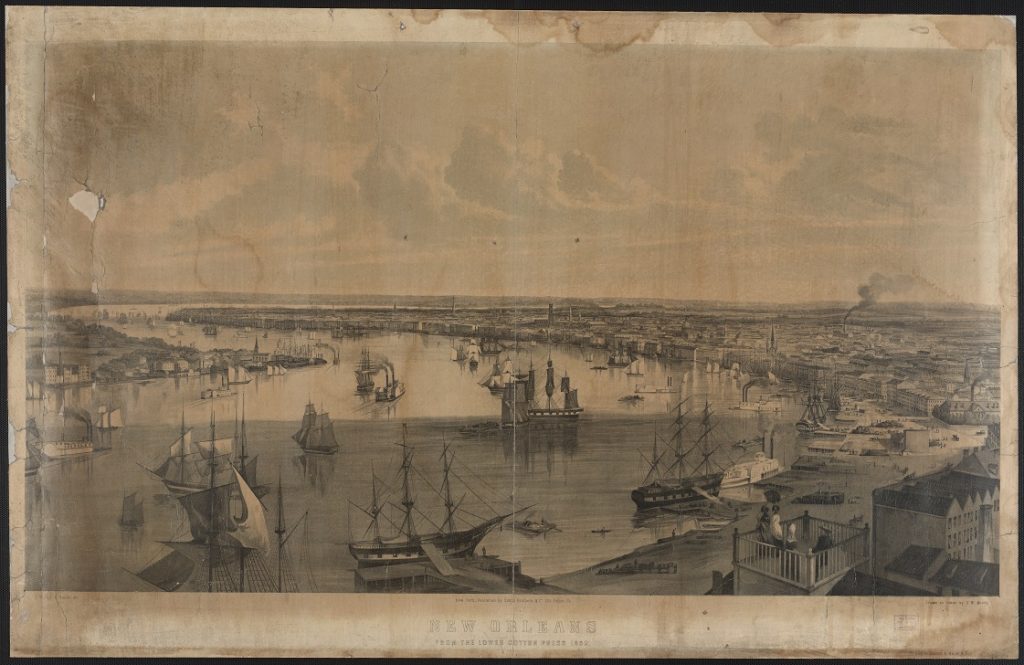

In 1803, the United States bought the Louisiana Territory from Napoléon Bonaparte. It contained many independent Native American nations, as well as New Orleans, which controlled the export of goods from the Mississippi River. Throughout the next several decades, Protestant Anglo-American settlers poured into Louisiana. This created tensions with the French Creole elite in New Orleans, who had been running the city since its founding. However, both the Creole and Anglo-American elites had similar incomes and rates of slave ownership. Their political competition was not about ideology, but over who would control the machinery of the city.[1]

In the beginning of the century, French Creoles easily maintained power in New Orleans, but as more and more Americans came into the city, they began to threaten Creole rule. There were reports of non-resident Americans coming into the city to vote. The Creoles, meanwhile, began to schedule elections during the summer, when many American residents periodically left New Orleans to avoid outbreaks of yellow fever. These actions caused tension between the established Creoles and the American newcomers. Eventually, a compromise was worked out in 1836, when the city was divided into three separate municipalities – one mostly Creole municipality, one mostly American municipality, and a municipality made up of immigrants. Each municipality controlled its own budgets and had separate police forces. There were only a few city-wide offices, and those that existed lacked any substantial power.[2]

The municipality system lasted throughout the 1840s. During this time, more Irish and Germans moved into the city, primarily settling in the third municipality. The American municipality also grew in numbers and in economic power. By 1850, the American municipality had $40 million in taxable property, compared to $20 million for the Creole municipality and $10 million for the immigrant municipality. Recognizing this gap in wealth, the Creoles advocated a merger of the three municipalities in order to discharge the debt held by the Creole and immigrant municipalities. The Americans understandably opposed this consolidation plan. Eventually, a compromise was agreed to, which consolidated the three municipalities along with the town of Lafayette, which was populated by mostly Americans.[3]

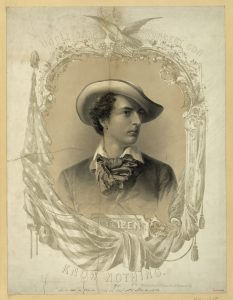

The early 1850s was a time of coalescing political identity, as Americans supported the Whigs and as Creoles and immigrants supported the Democrats. The Creoles cultivated a strong relationship with the Irish and Germans. By 1852, the Creoles gained control of the city police force. In subsequent elections, Americans charged that the Creoles brazenly committed voter fraud, enfranchising immigrants not eligible to vote and leading groups of immigrants to vote multiple times in different neighborhoods in the city. The Know-Nothings, a secret anti-immigrant organization, gained followers among the Americans in New Orleans. With the dissolution of the Whig Party, the Americans organized candidates under the Know-Nothing label, calling themselves the “Reform Party.” Elections in 1854 were rife with violence and corruption, as the Democrats engaged in voter fraud and the Know-Nothings attacked immigrants who showed up at the polls. This allowed the Know-Nothings to make some gains in the municipal elections. Violence between Know-Nothings and immigrants broke out after the election. The mayor even had to organize a special police force to restore order.[4]

It is worth noting that elections in the 1800s were largely conducted without a secret ballot – political parties would print their own tickets and distribute them, and the voter would take the ticket and deposit it in a public ballot box. This system allowed much more opportunities for corruption, cheating, and intimidation, as voters could be threatened at the polls, political parties could distribute forgeries, and political machines could bribe voters. All of these were common tactics in New Orleans throughout this period. Still, this system also allowed people who were illiterate or semi-literate to vote, which was very important given the lack of full literacy during this time.[5]

The Know-Nothings sought to exploit a political opening in the March 1855 election. Under Democratic control, the city went from having a $500,000 surplus to a $500,000 deficit. Decrying political corruption and financial malfeasance, the Know-Nothings attracted support and were able to win most of the municipal posts. Democrats charged that immigrants were unjustly turned away from the polls. Shortly after the election the Know-Nothings were able to gain full control of the local police board.[6]

In the subsequent election of 1855 in November, immigrants were beaten and even killed. An Irish immigrant, John Reilley, was shot and killed by assailants from a carriage. This violence proved to be effective as the Know-Nothing candidate Charles M. Waterman was elected. The 1856 Presidential election was also incredibly violent. The Know-Nothings again dominated the polls, even winning the pro-Democratic second and third districts. Immigrants were regularly attacked in the streets in weeks before and during the election. A Democratic member of the Louisiana Supreme Court, Thomas Slidell, was assaulted and died four years later, partially because of the wounds he sustained.[7]

In response to the violent 1856 election, Louisiana passed a law allowing officials to intervene in local New Orleans elections, but it had little effect. The Know-Nothings simply ignored the law, repressed Democratic voters, and decisively won the 1857 elections. Yet, in 1858, the Know-Nothings split as groups fought over the party machinery. The working-class took control of the local Know-Nothing clubs, while the wealthy elite, led by Waterman, sought to maintain control of the party. Seeing this split and determined to not allow Know-Nothing voter intimidation to influence the next election, the Creoles formed the Vigilance Committee in March.[8]

As the election approached, two political camps formed. The local Know-Nothing clubs supported Gerrard Stith for mayor, who received the formal party nomination. The Independent Know-Nothings under Waterman supported a reform candidate, P.G.T. Beauregard, a Creole and political novice, who gained fame for his exploits in the Mexican-American War and had vigorously supported Franklin Pierce’s presidential run. The Democrats, having failed to win an election for the previous three years in New Orleans, decided to support Beauregard as well. For the Creoles and immigrants, the 1858 election was a desperate battle for political survival.[9]

Political rhetoric between the two camps was heated. The New Orleans Daily Crescent, supporting Stith, declared that the Independents “may have more wealth on their ticket,” but questioned whether “the men on it are a whit more honest, intelligent or patriotic” than the Know-Nothing ticket. Beauregard, meanwhile, cast himself as the “’Standard Bearer’” against “those few enemies of the public good, who have for several years past been treading, with an iron and unsparing heel, upon the most sacred rights of this peaceful and much enduring community.” The acrimony burst into open conflict when the Vigilance Committee decided to mobilize only four days before the election.[10]

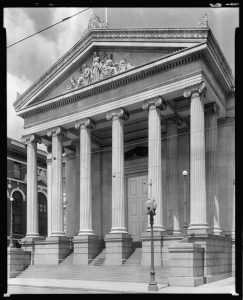

In the early morning of June 3, the Vigilance Committee took possession of the state arsenal, housed in the old Spanish Cabildo, and occupied Jackson Square. The two hundred armed men fortified the square with cannons and posted guards. They were led by Johnson K. Duncan, who was close to Beauregard. The pair had earlier worked on improvements to the U. S. Mint in New Orleans. Beauregard did not openly support Duncan, but also did not condemn him. In an announcement posted on June 4 and then sent to newspapers around the state, the Vigilance Committee declared that they “had temporarily seized the State Arsenal…with the view of freeing the city of New Orleans of the well-known and notorious ‘Thugs,’ outlaws, assassins, and murderers who infest it[.]” The city council demanded that Waterman organize an armed response to confront the Committee but he demurred. In response, the city council asked for Waterman to resign, which he refused. The meeting was adjourned without resolution, with the city council giving Waterman discretionary powers to deal with the situation. While Waterman still supported Beauregard, he did not agree with the action of the Vigilance Committee.[11]

A large group of Know-Nothing supporters gathered in Lafayette Square and armed themselves in preparation for battle. The square was quickly transformed into an armed camp. Meanwhile, Waterman met with Duncan in Jackson Square. Waterman asked Duncan to stand down, but he refused unless Waterman was willing to grant the Committee a special police commission through the election. Waterman said that he had no authority to do so and left.[12]

The next day Mayor Waterman again attempted to negotiate with the Vigilance Committee. This time Waterman simply acceded to Duncan’s demand for a special police commission through the election. Duncan stated that the armed men would hold their position until sworn in. Waterman announced this “compromise” to a crowd of Know-Nothing supporters near city hall, who received the news unfavorably. A group of them decided to roll a cannon down the street to attack Jackson Square. They dispersed quickly when a stray shot was fired. In Jackson Square, the Vigilance Committee mounted a propaganda campaign, immediately issuing a notice of the compromise with signatures from Waterman and Duncan.[13]

The city council grew impatient and demanded that Waterman return to city hall (today’s Gallier Hall). In response, Waterman deputized Stith, who organized a police force, turning away people who did not express support for the Know-Nothing Party. Waterman’s position was impossible. He had split from the Know-Nothing Party and supported Beauregard. Nonetheless, in this crisis, Waterman allowed Stith to create a special force that would oppose the Vigilance Committee, who supported Beauregard for mayor. The willingness of Waterman to deputize Stith suggests a he may have been trying to salvage his position with the city council, who was losing patience with him. Whatever his reasons, it appears Waterman wanted to forestall bloodshed. After working continuously for forty-eight hours though, Waterman needed sleep and retired to his room.[14]

The city council asked Stith to escort Waterman to city hall, but he refused to go, presumably afraid for his safety. Fed up with Waterman, the assistant board of alderman impeached him, and the city council appointed Henry M. Summers as mayor. He ordered the Vigilance Committee to disband, who unsurprisingly did not. The Vigilants fortified their position and renamed Jackson Square, “Fort Vigilance,” while the Know-Nothings dubbed Lafayette Square, “Fort Defiance.” Both sides largely stayed in their camps, neither risking a direct confrontation, though a few of Duncan’s scouts were accidently killed by their own men. Under this tense atmosphere, the election proceeded on June 7. The previous degree of overt voter intimidation and violence seen in 1855 and 1856 was not repeated, though there were reports of some intimidation in the immigrant-dominated third district. The Know-Nothings again won the elections, prevailing in all districts, except the Creole-dominated second district.[15]

The Vigilance Committee disbanded. Afterwards, some scattered legal actions were taken, but most of Duncan’s men were granted amnesty. Regardless, the 1858 election showed that the Know-Nothings had clearly consolidated power over the police force and election machinery. Beauregard narrowly lost, and the bitterness of the election slacked his appetite for politics. His attempts to enter politics after the Civil War were failures, including the Unification Movement, his support for failed presidential candidates Horace Greeley and Winfield Scott Hancock, and his brief tenure as city commissioner. He also turned down a nomination for state treasurer in 1878 [16]

In 1860 the Know-Nothing John Monroe, a former dockworker, was elected. It represented the victory of the working-class faction of the party and was surprising since elsewhere in the country the Know-Nothings were fast disappearing. In 1862 though the Union captured New Orleans and Monroe was imprisoned, destroying the Know-Nothings. That said, the 1850s saw the rise of working-class politics, anti-immigrant rhetoric, and the legitimization of violence to defeat political opponents. Each became part of New Orleans politics from Reconstruction until the days of Huey P. Long.

————

Sources:

[1] Soule, Leon C. The Know Nothing Party in New Orleans: A Reappraisal. (Louisiana Historical Association: Baton Rouge, LA, 1961), 4; Marius Carriere, “Political Leadership of the Louisiana Know-Nothing Party.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 21, No. 2 (Spring, 1980), 193. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4231987

[2] Ibid., 11-12, 14.

[3] Ibid., 23, 25.

[4] Ibid., 39, 47, 54-57; Sacher, John M. A Perfect War of Politics: Parties, Politicians, and Democracy in Louisiana, 1824-1861 (Baton Rouge, LA, 2003), 236-237.

[5] Schott, Matthew J. “Progressives Against Democracy: Electoral Reform in Louisiana, 1894-1921.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 20, No. 3 (Summer, 1979), 250. Still, Schott agrees with the historian J. Morgan Kausser that the straight ticket ballot used throughout the 19th century helped those who were illiterate or semi-literate vote. In fact, as Kausser and Schott argue, the introduction of the secret ballot in the South was a major means by the white elite to take away the franchise from black voters and ensure Democratic Party control. Schott, p. 249 – 251; Soule 54-56, 63

[6] Soule, 62,64-65. Some German and Irish immigrants certainly should not legally have had the right to vote, as Democratic-appointed judges sometimes granted immigrants naturalization far before they should have been legally able to naturalize (see Soule, pages 70-71).

[7] Ibid., 73, 79, 81-82.

[8] Soule, 90-95; Sacher, 267.

[9] Soule, 92-95.

[10] “The American Ticket,” The New Orleans Daily Crescent, May 31, 1858; “Address of Major [sic] G.T. Beauregard to the Independent voters of New Orleans,” Pointe Coupee Democrat, June 12, 1858. This was originally published on June 5th, before the election, but after the Vigilance Committee had occupied Jackson Square; Soule, 92-95.

[11] Office Executive Vigilance Committee. “Notice to the People and Citizens of New Orleans,” Pointe Coupee Democrat, June 12, 1858; Soule, 95, 97.

[12] Soule, 97-98

[13] Ibid., 98-99; Office Executive Vigilance Committee. “Notice to the People and Citizens of New Orleans,” Pointe Coupee Democrat, June 12, 1858. This notice was originally published on June 4th, the same day as the compromise.

[14] Soule, 100-101

[15] Ibid, 100-103

[16] Ibid, 100-103

Good stuff Sean.

Very interesting!

Where did the blacks and mulattoes fit in this historical period, Sean? All in all very useful for understanding later Louisiana history.

The free people of color made up 9% of the city’s population and varied from very wealthy, including slave owners, to dockworkers. The richer ones tended to be mixed race, Catholic, and Creole. They could not vote.

Beauregard was attacked as being too friendly with the FPOC. He had relatives and friends among the FPOC and the Know-Nothings of New Orleans supported stricter restrictions on the FPOC. However, it was not a central part of the race for mayor.

Excellent introduction to the convoluted nature of antebellum Louisiana politics, and PGT Beauregard’s foray into that labyrinth. By revealing his willingness to enter politics “when necessary,” even while serving as a military officer, Beauregard may have unwittingly set the ground work for “concern” later, Autumn of 1861, when the too-successful Rebel General was promoted as “potential Confederate President,” further straining relations with provisional President Jefferson Davis.

One of my points in my Beauregard upcoming book is that he was a brilliant engineer and a talented general, but a very poor politician and that limited his success as a general and a railroad executive.

I have been a Beauregard since forever, even though I am definitely a Yankee. I am really looking forward to your book.

Amazing how local politics can be a confusing stew of race, class and tribe. Not all that different in some ways from Manhattan and Baltimore!

Nice post. Thanks.