Edwin V. Sumner, Fredericksburg, and Lessons Learned Along the Chickahominy

Ambrose Burnside’s campaign in the winter of 1862 went belly-up because of his inability to get across the Rappahannock River. Standing on the far bank of the river, swollen because of winter rain and snow, Burnside could do nothing but wait for pontoon boats while Robert E. Lee’s army marched into position and set up killing zones outside of town. Thus, it is a common (and understandable) question that so many visitors to the battlefield ask: Why didn’t Burnside find another way across? In fact, many authors here at ECW have written about Burnside, his dilemmas, and even explained why it wasn’t feasible to use fords across the river. This post is another one of those explanations, but has little to do with Burnside himself. Instead, this post will look at one of Burnside’s subordinates, Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner, and how a battle six months before Fredericksburg impacted the army’s actions (or inaction) along the banks of the Rappahannock.

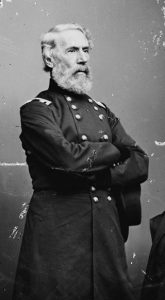

Edwin Vose Sumner had already been in the army for five years before Ambrose Burnside was even born. Himself born in 1797, Sumner joined the army in 1819, and would serve for the next 44 years. He was a no-nonsense kind of officer and earned the moniker of “Old Bull Head” when a musket ball bounced off his head at the 1847 battle of Cerro Gordo. By the spring of 1862 Sumner was promoted to command the Army of the Potomac’s Second Corps and led it through the opening phases of the Peninsula Campaign.

As the Army of the Potomac neared Richmond, it struggled with poor weather. Over the month of May 1862, it rained on sixteen of the thirty-one days. With that incessant downpour, the Chickahominy River rose and became a swirling mass of water. As the Confederates fell back towards Richmond, they destroyed the bridges across the swollen Chickahominy, leaving the Army of the Potomac to make their own.

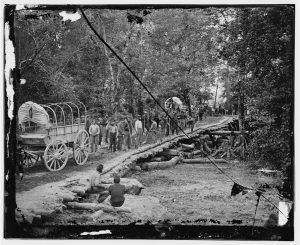

Sumner’s men started construction, making do with what they could. The regimental historian of the 5th New Hampshire wrote described crossing point that they were to bridge as, “about forty yards wide, but all through the swamp the water, dark and foul, was from three to six feet deep. The swamp itself was a mass of rank vegetation, huge trees, saplings, bushes, grapevines and creeping plants.” Summarizing, the historian said, “It really was an immense undertaking.”[1] With water up to and over their waists, the soldiers worked for two days, using grapevines to lash the log buttresses together to replace the rope they lacked. Upon inspection, Sumner christened the project the Grapevine Bridge. Another bridge was built by other Second Corps soldiers that came to be known as the Lower Bridge. For the Second Army Corps, they were the only two viable crossing points of the Chickahominy. And that was before the worst of the rain.

On May 30 the water came down in buckets. A chaplain in the Second Corps wrote later, “the windows of the clouds were wide open, and torrents of water poured out. Lightnings, like zigzag arrows of fire, darted to the earth, followed by long rolls of thunder.”[2] The Chickahominy got even deeper, and even wider.

In the middle of all this rain, the Army of the Potomac was dangerously split. The Third and Fourth Corps were both on the opposite side of the Chickahominy, cut off from the rest of the army by the river. If they were to be attacked, they would be on their own until reinforcements could get across.

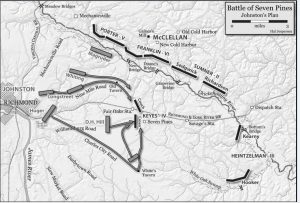

And by the fates of history, that is exactly what happened. Sensing a chance to strike a blow against the Federals, Joseph Johnston’s Confederates attacked the next day, May 31, in the opening phases of what came to be known as the battle of Seven Pines (or Fair Oaks, to the Federals). The Confederates slammed into the Fourth Corps and fighting see-sawed back and forth. Samuel Heintzelman’s Third Corps came up to support, but more help was needed. Orders went out for Sumner to reinforce the beleaguered two corps, but that required crossing the Chickahominy.

“The river had risen during the night and morning,” Alexander Webb wrote later, “the causeways approaching the bridge on either side were overflowed, and the bridges, trembling under the strong current which covered the planking, where in momentary danger of destruction.”[3] In the aftermath of the torrent of rain and mud, the Lower Bridge washed away, leaving just the Grapevine intact. From the far side of the river came the crescendo of battle, and Sumner knew he needed to get men across.

But the engineer overseeing the Grapevine hesitated. He protested to Sumner, telling him, “Don’t you see the approaches are breaking up and the logs displaced? It is impossible!”

Sumner roared in his saddle, “Sir, I tell you I can cross. I am ordered!”[4] With Sumner leading the way, his soldiers darted across the bridge. The engineer who had protested later wrote that the Grapevine “swayed to and fro to the angry flood below or the living freight above, settling down and grasping the solid stumps.” Soon after two of Sumner’s divisions had crossed, the Grapevine finally gave way, collapsing down into the Chickahominy.[5]

With Sumner’s support, the Federal line held. But for the rough-looking Grapevine Bridge and Sumner’s own tenacity, the battle of Seven Pines could have turned disastrous for the split Army of the Potomac. Instead, it lived to fight another day.

Sumner recognized how close it was, though. And he remembered the risks and odds along the Chickahominy. Which brings us to November 1862, along the banks of another river swelled with recent rain.

Marching as the vanguard of the Army of the Potomac, Sumner’s men reached Falmouth, opposite Fredericksburg, on November 17. A tiny force of Confederates held Fredericksburg, and an obnoxious battery of artillery opened fire on Sumner’s men. As Federal guns unlimbered to return the fire, Sumner spurred forward to send infantry across the Rappahannock, silence the enemy guns, and capture Fredericksburg. But then he stopped.

The Rappahannock gets its name from the Algonquin, meaning, roughly, “Rapidly Rising Water.” Even if Sumner did not know the etymological meaning of the river in front of him, he recognized its power. The Rappahannock was both wider and deeper (much deeper) than the Chickahominy just six months ago. Rain and snow in the days prior to Sumner’s arrival at Falmouth caused the Rappahannock to rise even more. Could he send infantry across by themselves to capture the town? Perhaps, but then they would be in the exact same situation as the Federals at Seven Pines. He would not be able to get artillery or wagons across, and the Rappahannock was mightier than the ability to throw an impromptu bridge like the Grapevine together. Later, after the debacle at Fredericksburg, Sumner testified to Congress, and explained why he did not cross on that fateful first day. First, his superior, Burnside had ordered him not to, simple as that. But more than that, Sumner added, “There was another reason too: I had had little too much experience on the peninsula of the consequence of getting astride a river to risk it here. For these two reasons I revoked my order [to cross].”[6]

The Army of the Potomac, for better or worse, would wait for the pontoon boats to arrive. We know, nearly 160 years later, that the pontoons would not arrive before Robert E. Lee’s Confederates. We know that Fredericksburg would turn into a one-sided bloodbath because of that, but Ambrose Burnside and Edwin Sumner did not. All they had to go on was their previous experiences, and for Sumner, that meant remembering the flooded Chickahominy and deciding it was not worth the risk along the Rappahannock. Whether or not that was the right decision remains for the historians to debate.

______________________________________________________________

[1] William Child, A History of the Fifth Regiment, New Hampshire Volunteers, in the American Civil War, 1861-1865 (Bristol: R.W. Musgrove, 1893), 64.

[2] Edward D. Neill, “Incidents of the Battles of Fair Oaks and Malvern Hill,” in Glimpses of the Nation’s Struggle, Third Series (New York: D.D. Merrill Company, 1893), 456.

[3] Alexander S. Webb, The Peninsula: McClellan’s Campaign of 1862 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908), 111.

[4] O.O. Howard, Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard, Vol. 1 (New York: The Baker & Taylor Company, 1907), 237.

[5] B.L. Alexander, “The Peninsular Campaign,” in The Atlantic Monthly, Vol 13 (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1864), 382.

[6] Testimony of Edwin V. Sumner, in Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing, 1863), 657.

Excellent perspective. Without taking into account someone’s prior experiences, it is difficult to fully appreciate their thinking in a given situation.

Thanks Chris! I agree, it’s important to know what previous experiences and perspectives people had so we can better understand their decision making.

Hmmm. Sounds like a prelude to “Take the hill, if practicable…”

Definitely along the same line of thought, with Lee in this case being used to be able to using vague orders with no clear set of directions or commander’s intent. Those experiences had to change with a new command staff.

This is a nice post. As an aside, Sumner’s three batteries had a lot of trouble at Seven Pines crossing with him, due to the flooded turf on either end of the bridges and the soil comprising the roads, which were ultisols that turned into quagmires after the torrents that fell the night before. The gunners had to wrestle with guns that sank up to their axles in the muck. I’m trying to imagine what i would have thought to myself if i were a Yank artillerist and I heard Bull bellow that “I” could cross,

Thanks for the comment, John. Artillery is for sure its own burden, a problem both, in this example at least, at the Chickahominy and Rappahannock.

Ryan: As a guy whose ancestor helped build one of those bridges, I’ve resisted weighing in with a defense of the workmanship. 🙂

The career Army officer, E.V. Sumner, had over three decades of experience when he was assigned to Kansas in the mid-1850s, tasked with “pacifying” Native Americans and keeping the peace between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces. At the time, Slavery was lawful, including in Kansas Territory; and Sumner’s efforts were likely seen as “pro-slavery” as he attempted to enforce the law as directed by political masters.

Colonel Sumner appears to have taken an anti-secession stand in late 1860 and availed himself in support of President-elect Abraham Lincoln: offering self-defense advise; riding with Lincoln from Illinois to Pennsylvania; and agreeing to being sent west to California after Lincoln’s inauguration in order to replace just-resigned General Albert Sidney Johnston (who had decided to throw in his lot with the seceded State of Texas.) In California, Sumner had LtCol Don Carlos Buell as his Assistant Adjutant General (Buell had delivered crucial messages to Colonel Robert Anderson at Fort Moultrie, which may have authorized Anderson’s move to Fort Sumter.)

There is no doubt that E.V. Sumner was “long in the tooth” at the time of the Civil War. But sometimes incompetence (loss of potency) can only by revealed in action on the field. To his credit, General Sumner requested his own relief from command.

Sumner certainly had a long career full of ups and downs. His command decisions at Williamsburg were pretty lacking, too. But I would say on the whole he was a reliable subordinate whose opinions helped mold the Army of the Potomac. Ill health, too, led to him requesting his relief. He died in March 1863.

E. V. Sumner gets mentioned so infrequently, that this appeared to be an opportunity to introduce another taboo topic: California and the Confederacy. Many in the South were incensed by the admission of the Golden State to the Union as a Free State; and there was continual talk through the 1850s about overturning that “wrong decision.” Jefferson Davis, himself, was in favor of this element of Confederate expansionism. Think Railroads; and the Gadsden Purchase.

Was it a serious threat? That is still to be determined… But if interested, have a view of the recent YouTube video “California and CSA expansionism,” featuring John Heckman and Brendan Harris: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4I2Ef6rpjFc

Great article! (A musket ball bounced off his head?!)

Thanks for reading and the comment! That’s the story at least. My guess is it was a musket ball that had used up all its velocity at extreme range. Still a pretty humorous way to get a nickname, though.