A Doctor, His Enslaved Man, and North Georgia’s Union Circle (part one)

Dr. Berry Gideon, his wife, and seven daughters watched helplessly as flames devoured their home next to the Western and Atlantic Railroad, between the towns of Calhoun and Resaca, on June 18, 1864. Union soldiers allowed the family fifteen minutes to remove their most precious belongings before setting the dwelling ablaze. Locals had suggested that the doctor was complicit in the recent bombing of a Union train on the tracks near his house. In reality, it was irregular Confederate scouts who had placed the bomb under the engine during the night. Many of Gideon’s neighbors were happy to see their local physician punished for his stubborn loyalty to the old Union.

Berry Gideon was born in 1801, the second son of the Rev. James Gideon Jr. of Washington County. His father died when Berry was just fifteen years old, but left most of his estate to ensure that his two sons would receive a classical education. Berry served in the Seminole Wars in 1818, first residing in Cassville, the seat of Cass (now Bartow) County. Dr. Gideon was just one of a large number of Georgia residents who had opposed disunion from the onset of America’s sectional strife. In 1835, he spoke out strongly against those South Carolinian and Georgian men who believed that state authority superseded that of the federal government. “Perseverance and consistency, tempered with wisdom, made the Greeks wise, and the Romans great,” he argued. “Unionists of Cass , never forget this.” He refused his party’s nomination to the state legislature in 1839.

The young doctor was one of Gordon county’s pioneer white residents, settling on 420 acres of Cherokee lands about two miles north of what later became the town of Calhoun. He owned a subsistence farm of about 83 cleared acres, worked by one enslaved man. An enslaved woman and her daughter did household chores for Gideon’s wife and their eleven children. By 1860, the fifty-nine-year-old country doctor had amassed a modest fortune, including a valuable library of medical texts and a large inventory of medicine.[i]

Gideon engaged in public debate on the secession question shortly after Lincoln’s election, arguing that slave states had neither right nor cause to separate from a constitutional Union that had brought them unparalleled prosperity. Committed Unionists like Gideon did not cooperate with the new Confederate government; rather, they conspired to thwart the rebels. Such efforts were fraught with risk.[ii]

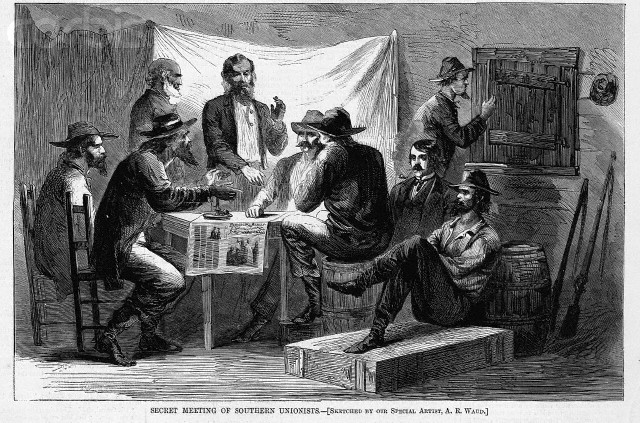

Resistance to the new Confederate government was widespread in north Georgia from the very beginning of the Civil War. In December 1861, Georgia governor Joseph E. Brown learned that Gordon County Unionists were meeting in secret and organizing armed militias to safeguard themselves and their families against threats from local officials and rebel neighbors. These men vowed to avoid serving in the Confederate Army, aid Federal troops if they reached the Empire State, and even “help the Negroes” in the event of slave insurrection.[iii] Many remained true to this oath during the summer and fall of 1863 and again in 1864, when the war came to their doorsteps.

Confederate legislators passed the first of three conscription acts on April 21, 1862. By the fall, the age range for draftees had been extended upward to 45 years. An exemption for owners of at least twenty slaves was added and exempted occupations scaled back. Union men who could previously avoid rebel military service were hounded by conscript agents in a furious attempt to replace dead, sick, and deserting rebel soldiers as the scale of the violence grew to epic proportions. As Union armies crept closer to Chattanooga in the summer of 1863, the secret circle of Gordon County dissidents, including Dr. Gideon, became bold in their efforts to disrupt the Confederate war machine.

Georgia Unionists had an “underground railroad” that had nothing to do with escaped slaves. Its purpose was to aid Confederate deserters and Union dissenters in getting to safety behind Union lines. Dr. Gideon’s property included a shallow ford on the Oostanaula River, where he would float refugees across on log rafts. Networks of safe houses, secret passwords, and secure communications created a refugee aid effort that was organized, efficient, and highly successful, despite consistent efforts by Confederate authorities and irregular scouts to hamper the initiative. Nevertheless, numerous Union men and at least one woman were killed by rebel guerrillas and bandits roaming the countryside, targeting “Tory” families. Others were hanged or shot, yet still managed to survive.[iv]

One of the ringleaders of the underground railroad in north Georgia was Jerimiah B.N. Adams of Tilton. On one occasion in February 1864, Adams organized a company of 49 men to go through the lines to Chattanooga. All but six made it. Their guide was captured, but later escaped. Adams remained behind Union lines from early 1864 through the end of the war, working as a foreman on the railroad.[v] Other Union men evaded conscript agents by joining state guard units, which many volunteers did not expect would see more than home guard service. In Gordon and Murray counties, the preferred “Yankee layout” was Colonel Edward M. Galt’s First Georgia State Guards, more popularly known as “Joe Brown’s Pets.”

Captain Blair Mays’s company, a home guard unit nicknamed the “Resaca Guards,” included dozens of leading Unionists who lived in the vicinity of the Western and Atlantic Railroad south of Dalton and whose main charge was guarding the railroad line. In August 1863, Mays complained to his superiors that he had 57 volunteers and “nearly all refuse to be mustered in.” He feared that his company “would go by the board in Georgia,” and that the governor might need to “order a draft for our special benefit.”[vi]

Dr. Gideon’s two sons served in the Confederate Army. Such inter-generational splits between strong Unionist fathers and eager rebel sons were common in north Georgia. The doctor’s eldest son Galen had moved to Texas in 1850. He enlisted as a private on July 2, 1862, at Sherman, Grayson County, Texas, in Capt. John L. Randolph’s Company of the First Battalion of Texas Partisan Rangers. His younger brother Gilead Gideon joined Joe Brown’s Pets on May 13, 1862 but later claimed that he deserted “at the first opportunity.” Given that he did not desert until August 5, 1864, that claim may be exaggerated. He was released on September 1, 1864 by Gen. George H. Thomas to work on the Union railroad.[vii]

By the fall of 1863, the Confederate Army was running out of food. Foragers made numerous expeditions to area farms, stripping corn off the stalks. They visited Dr. Gideon’s property, taking corn and oats. When Gideon asked for payment vouchers, the soldiers laughed at him. Then they made the mistake of killing his sheep. The doctor grabbed his shotgun and wounded one solider, driving the rest of the small party away. A month later, a Confederate quartermaster arrived at his door and threatened to hang him. Gideon denied shooting the poachers.

Nervous Georgians anticipated Union Gen. W.T. Sherman’s eventual move south from Chattanooga during the spring of 1864. The first major battle of Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign was waged just a few miles north of the Gideon homestead on May 13 ? 15. In the aftermath of the Battle of Resaca, nearly 100,000 Union troops and their animals needed food, so they fanned out across the region. On May 16, Federal soldiers reached the Gideon farm, taking some of his bacon and a cow but leaving some food for the family. They took about a third of his drugs and medicine for their wounded and sick comrades. They returned for more the next month.

Dr. Gideon convinced General Green Berry Raum to post a guard at his house; but after that captain left, looting Federals ransacked the premises. One solider slipped away with a jar filled with more than $700 in gold and silver. Others dismantled his barn, stable, office, and blacksmith shop to use for shanties and a blockhouse fortification on the railroad line. The doctor was left with little to help feed his large family. Only aid from U.S. Army authorities kept them and dozens of other area families from starvation over the next year.[viii]

Other loyal neighbors were in similar circumstances; yet many continued to aid the Union cause. In July, a group of local men captured a rebel lieutenant and eight soldiers of the Ninth Kentucky Infantry near the village of Fairmount, a noted Union neighborhood. While marching their captives to Calhoun, the loyalists were intercepted by Confederate scouts and captured. Two hours later, The Fifth Kentucky Infantry (US) came to their aid, recaptured the rebels, and transported them to Calhoun.[ix]

To be continued…

Sources:

[i] Claim #11,472, Berry W. Gideon, Gordon Co., Ga., 1874, Southern Claims Commission (hereinafter abbreviated as “SCC.” Accessed through Ancestry.com. Testimony of claimant. Will of James Gideon, Jr., 1817, Jackson Co. will book A, p. 68. Thanks to Harold Duke, the ggg grandson of Berry Gideon and to Jeff Henderson of the Gordon Country Historical Society for information on Berry and Owen Gideon.

[ii] Claim #11,472, Berry W. Gideon, SCC. Georgia Pioneer, 13 July, 1835, 29 March, 1839.

[iii] L.R. Ramsaur to Gov. Joseph E. Brown, 14 December 1861, Governor’s Incoming Correspondence, Georgia Department of Archives and History, Morrow.

[iv] Numerous witnesses used the term “underground railroad” to describe the network aiding deserters and Unionist refugees in north Georgia. See, for example: Claim # 15,829, Daniel L. Cline, Whitfield Co, Ga., 1877, SCC. Testimony of Francis M. Anderson; Claim #2590, Sidney Defoor, Gordon Co. Ga., 1878, SCC. Testimony of claimant; Claim #801, Thomas Bird, Sr., Gordon Co., Ga., 1878, SCC. Testimony of claimant.

[v] Claim 13,385, J.B.N. Adams, Whitfield Co., Ga., 1877, SCC. Testimony of claimant.

[vi] Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of

Georgia, B.R. Mayes. RG 109. Microfilm publication M266, Roll 129, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[vii] Records of the War Department Relating to Confederates, Records relating to prisoners, oaths, and paroles. Microfilm publication M598, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[viii] Claim #11,472, Berry W. Gideon, SCC. Lt. Albert Snow, “List of Destitute Citizens that are entitled to Govt. Rations.” July 4, 1865. Gordon County Historical Society.

[ix] War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), series 1, vol. 38, pt. 2, p. 866.

Intriguing information about Unionism in GA.