Sherman’s “Demon Spirit”

In a letter written on April 29, 1863, to his wife Ellen, William T. Sherman privately expressed his misgivings about the Vicksburg campaign Ulysses S. Grant was just then launching. “My own opinion is that this whole plan of attack on Vicksburg will fail must fail, and the fault will be on us all of course,” he wrote.

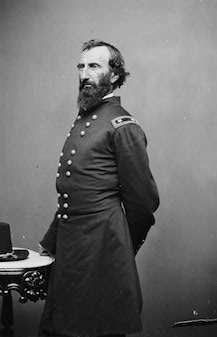

The entire letter is quite extraordinary, but what really jumps out at me is the venom Sherman holds for fellow corps commander John McClernand. McClernand, a highly influential political general commanding the XIII Corps, was the most senior of Grant’s subordinates. Sherman despised McClernand, who outranked him and thus superseded him in command following Sherman’s defeat at Chickasaw Bayou in late December 1862. That replacement, Sherman later admitted, was “the severest test of my patriotism.”

“The Noises & clamor have produced their fruits. Even Grant is cowed & afraid of the newspapers,” Sherman wrote, suspecting machinations behind the outcry.

Should as the papers now intimate Grant be relieved & McClernand left in command, you may expect to hear of me at St. Louis, for I will not serve under McClernand. He is the impersonation of my Demon Spirit, not a shade of respect for truth, when falsehood is easier manufactured & fitted to his purpose: an overtowering ambition and utter ignorance of the first principles of war. I have in my possession his orders to do “certain things” which he would be ashamed of now. He knows I saw him cow at Shiloh. He knows he blundered in ignorance at the Post & came to me beseechingly, “Sherman what shall we do now?” And yet no sooner is the tempest past, and the pen in hand, his star is to be brightened and none so used to abuse, none so patient under it as Sherman. And therefore Glory at Sherman’s expense.

“Demon Spirit”! Can you believe that? He calls out McClernand as a liar and a coward, too, with “Overtowering ambition.” Harsh words.

Sherman’s reference to “the Post” was Arkansas Post, a Confederate garrison 45 miles upstream from the mouth of the Arkansas River. Federal forces captured it on January 11, 1863, as part of their operations against Vicksburg (see more, here, from the American Battlefield Trust). McClernand wrote a self-adulatory report of the battle, ignoring Sherman’s key role, further insulting the bruised feelings of the resentful Sherman.

Even after Grant arrived from Memphis in early February to take personal command of operations in the field, tensions between Sherman and McClernand continued to simmer, and Sherman became convinced it was only a matter of time before McClernand slipped him a Brutus-like dagger. “I avoid McClernand, because I know he is envious & jealous of everybody who stands in his way,” Sherman told Ellen earlier in April. “He knows I appreciate him truly and therefore he would ruin me if he could.”

“Appreciate” here serves as a euphemism for “see through him clear as day and recognize him as the smarmy political snake he is.” While that’s my translation, not Sherman’s exact words, he does express a similar sentiment on a February 6 letter to Ellen. “[H]e is a most deceitful man, taking all possible advantage and having no standard of truth & honor but the public clamor,” he wrote.

The context of the April 29 letter, though, stand out because it seems to be written while Sherman was sunk in one of the dark moods he was sometimes prone to. He did not have confidence in Grant’s overall plan for crossing the Mississippi and making an overland attempt on Vicksburg from the rear. Sherman’s own part of that plan entailed making an up-river demonstration against Confederate forces near the Yazoo River to keep their attention fixed there while Grant moved downriver and crossed. “I think Grant will make a safe lodgment at Grand Gulf,” Sherman confided to Ellen,

but the real trouble is and will be the maintenance of the army there. If the capture of Holly Springs [on December 20, 1862] made him leave the Tallahatchie, how much more precarious is his position now below Vicksburg with every pound of provision, forage and ammunition to float past the seven miles of batteries at Vicksburg or be hauled thirty-seven miles along a narrow boggy road?

Sherman himself would eventually supply the answer to this very question. Grant would assign the division of Maj. Gen. Francis Preston Blair of Sherman’s XV Corps to oversee the movement of supplies from Grand Gulf up to the rest of the army as it moved through the Mississippi interior. Sherman characterized Blair in the same category of political general as McClernand, “mere politicians who come to fight not for the real glory & success of the nation, but for their own individual aggrandizement.” Yet Blair would rise to the challenge and keep Grant’s army supplied as it moved, even as the army’s successes made a believer of the dutiful-but-pessimistic Sherman along the way.

Those successes, though, did nothing to soften Sherman’s attitudes toward McClernand, who performed solidly during the overland campaign and at least as well as the other corps commanders in the assaults against Vicksburg itself. Sherman condemned him, by his own actions, as a man “full of vain-glory and hypocrisy” and enamored by a “process of self-flattery,” and there was no changing his mind.[5] The venom Sherman expressed toward his “Demon Spirit” in his letter to Ellen only concentrated over time, as McClernand would come to regret.

————

You can read the full text of Sherman’s April 29, 1863, letter to Ellen at General Sherman’s Blog, created by a “JJ Brownyneal” during the Civil War Sesquicentennial to offer a day-by-day account of Sherman in the war. Other correspondence is also reprinted there, although the blog’s first-person “voice of Sherman” is a fictional construct.

General Sherman was simply a Grant horse-holder and brown-noser of the first order. And here he is trying to transfer all his own sins to McClernand. McClernard was at least as good a general as Sherman. Of course that’s not saying much.

I think McClernand seemed to perform pretty solidly. His problem was that he kept shooting off his mouth to the press.

Exactly. Didn’t he issue one of his “general orders” saying it was his corps who had done all the fighting? There’s a reason Grant relieved him of duty!!

It is somewhat humorous to read about Sherman criticizing”political generals” when the salvation of his own career rested partly in the influence of his politically powerful family and it’s connections. I will preface my following comments by admitting a profound dislike of the Sherman worshipping that seems to be de rigeur among some these days. Much has less to do with any perceived tactical skill than with the rigor of his methods in Georgia and the Carolinas. I think his dislike of McClernand lay in his fear of the latter being a success and supplanting Grant. Over the bulk of 1862, Sherman’s somewhat fragile sense of worth had been significantly tied up in his loyalty to Grant. Grant replayed loyalty with loyalty. He knew that McClernand, however patriotic, was ultimately only motivated by self interest.

Some great insights, John, and I agree with you. I don’t have anything against Sherman, but I do think he’s not the brilliant combat fighter everyone gives him credit for. Shiloh and Missionary Ridge are great examples of that.

McClernand is an interesting figure to me. I’m just getting to know him better.

I think all the War Democrats are worth a study, in part because they prevented the Radical Republicans from blotting out the “loyal opposition” as Copperheads. After the war, many assisted in rebuilding the Party.

Ability in combat was not why Sherman was a brilliant general. In the Civil War, fighting head on was a losing strategy.

Sherman won his reputation for adopting and applying modern tactics. In the Civil War, defensive positions became nearly unbeatable. The offensive tactic of the Mexican War, bringing cannons close enough to blow holes in the defenses, no longer worked. Rifling had made marksman accurate enough to pick off the cannon crews before they were in range. Frontal assaults were no longer effective. The alternative was flanking the enemy and destroying the supply lines. Sherman was a master of flanking tactics. The Atlanta campaign was a series of brilliant flanking maneuvers that forced the Confederates to repeatedly retreat all the way from the impregnable fortress of Dalton, GA to Atlanta. The siege of Atlanta ended when Sherman sent most of his army on a flanking maneuver that cut off all railroads leading to Atlanta while maintaining sufficient force to defend his position north of Atlanta. Sherman’s march to the sea and march through the Carolinas were successful because they avoided a major battle. (The largest battle was at Bentonville, NC near the end of his marches.) Sherman left the enemy uncertain about his objectives, and thus prevented them from massing sufficient force to stop or slow his progress. Sherman’s objective was not to fight an enemy army but to destroy the ability of the South to supply its coastal forts and armies. The ability of Sherman’s army to rapidly cross the swamps of SC in winter was an amazing feat that left the enemy with too little time to prepare. Adopting a modern strategy made Sherman an effective general. Tactics in battle were pretty standard and nothing special.

To Sherman, war was hell and no glory could be had. Sherman understood that the war could not be won by defeating armies. The ability and will of the people to fight had to be crushed. Sherman marched his army from Atlanta to Savannah without much resistance destroying the ability of the South to adequately supply its armies. Thousands of slaves followed Sherman’s army to freedom, proving to the wealthy planters that war would not prevent them from losing their slaves. As Sherman put it, “All the powers of earth cannot restore to them their slaves, any more than their dead grandfathers.”

If slavery was lost, what was the point of continuing the war? If armies were starving and could not be supplied, how could they continue to fight? If soldiers were deserting to protect their property from Sherman’s bummers how could armies hold together. If armies could not protect the people in the path of Sherman’s army why should they support the war effort? Sherman effectively implemented the strategy that ended the war.

Wow. Commanding officers in the same army not liking or trusting each other during the Civil War. Who would have ever thought? It’s kinda easy to understand the ‘CYA’ attitude that prevailed in both armies given how easy it was to be arrested and/or court-martialed for things that did and did not happen on the field of battle. Not to mention the Congressional oversight such as that by the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. ‘Political generals’ were often disliked and distrusted in both armies, while some did perform well. I think when this is all added up, there really is no “there” there. It was typical of so many then.

Sounds like Sherman had his number. But Sherman was not the only corps commander fed up with McClernand. Grant certainly had support for sacking him.

McPherson was as equally annoyed with McClernand as Sherman was.

General McClernand had a habit of sending press releases that embellished himself and denigrated others. McClernand was trying to set himself up as the man who captured Vicksburg and opened the Mississippi River to commerce. During the siege of Vicksburg, McClernand sent a missive that infuriated the other officers including General Blair. The uproar led General Grant to relieve McClernand of command on June 18, 1863.

Grant’s Vicksburg campaign was a huge gamble. Once Grant was on the east bank of the Mississippi, getting sufficient supplies was problematic. Grant had good reason to believe that he could supply his army by “living off the land”. Grant’s attack on Vicksburg the previous December had failed when Van Dorn destroyed Grant’s supply base in his rear. Grant was forced to retreat, but collected food and supplies on his retreat. Living off the land was more than sufficient. Grant applied that lesson to his Vicksburg campaign. Living off the land can be done when an army is moving but not when stationary. That meant that movements had to be quick and a supply line reestablished.

Grant’s unorthodox approach to Vicksburg confused the Confederates who tried to find and attack non-existent supply lines. Grant was aided by being on the south and east Bank of the Big Black River while Pemberton and Vicksburg were on the north and west banks. Grant’s army could hold the crossings with small forces as the rest of the force advanced. Pemberton commanded a garrison force that was not equipped for offensive attacks.

Unencumbered by massive supplies, Sherman’s divisions were highly mobile. His troops finished crossing the river on May 8, On May 14th, less than a week later, Sherman’s troops were in Jackson destroying the railroad before Confederate reinforcements could arrive and be supplied by rail. After destroying railroads around Jackson for 2 days, Sherman’s troops rapidly moved on Vicksburg passing the main engaged forces and connecting with the Mississippi River north of Vicksburg on May 18. The army was now guaranteed supplies from the Mississippi River.

Following the “removal” of Major General Lew Wallace in June 1862 from command of the Third Division (U.S. Grant performed that duty in Memphis for MGen Henry Halleck) former-friend of Grant, John McClernand saw the writing on the wall and took a leave of absence from the Army of the Tennessee and wound up in the East, where he met with his benefactor, President Abraham Lincoln, and convinced that man HE (McClernand) could take Vicksburg if permitted command of a Corps of personally recruited troops. Lincoln granted that request; McClernand recruited thousands of men from the Midwest and returned to Tennessee with President Lincoln’s authority to command a Corps of troops, and Major General Sherman (who had cooperated closely with McClernand to avoid defeat at the April 1862 Battle of Shiloh) was given a Corps. Both corps were under command of Major General John McClernand. [Non-West Point McClernand was senior to Sherman due date of rank; but junior to MGen U.S. Grant.]

It is said that McClernand was convinced by William Sherman that he did not possess enough troops to take Vicksburg; but an operation against Arkansas Post could be accomplished. The time and resources wasted in that successful joint Army/ Navy operation resulted in McClernand’s return to the Army of the Tennessee (under Grant’s command) and the renumbering of McClernand’s First Corps as Thirteenth Corps. (And Sherman’s Second Corps became the Fifteenth Corps.)

John McClernand was personally brave, loyal to the Union, and an effective leader and General. Although of the Democrat Party, he had the ear of President Lincoln, and may have suffered jealousy from his peers on that account. McClernand suffered a falling out with friend and mentor U.S. Grant over “lack of effective pursuit following Fort Henry in FEB 1862” and “offering unrequested advice” …and it was all downhill between the two strong-willed men from there. Grant bided his time; found an opportunity; and replaced McClernand with Ord during the Vicksburg Siege.

In sum: the relationship Grant ys. McClernand was both personality conflict and toxic rivalry, writ large.

References: Post of Arkansas by Robert S. Huffstot

OR 22 parts 1 and 2 [Arkansas Post]

OR 24 parts 1- 3 [Vicksburg]

Well put. And Grant was a master at picking the right moment to strike, politically if not as well militarily.

Lew Wallace wasn’t a big McClernand fan either. In his memoirs, he claimed McClernand was dishonest in his official reports and took more credit than he was due. So it was not a matter of just the West Pointers having issues with McClernand.

Sherman and McClernand fought together at Shiloh, their divisions holding the right flank on April 6 and attacking together on April 7. Each complimented the other in their reports and in letters after the battle. I think what happened is Halleck did not like McClernand. Grant, already wary of McClernand affier the Kountz affair, hitched his star to Halleck (their relationship is one of the most complicated of the war). Sherman, already a Halleck favorite, saw where the wind was blowing.

By 1865 most of the Union high command (Grant, Sherman, Ord, Pope, Schofield, Sheridan, Canby) consisted of Halleck’s favorites. McPherson, another Halleck favorite, would have been in that number if he had not died The two exceptions were Thomas and Meade, and Halleck tried to remove both of them in 1864 but they were shielded. Grant took a liking to Meade while Thomas was friends with Sherman, although it was a strained friendship by 1864. More importantly, each also had the full support of the subordinates they commanded, so removing Meade or Thomas would have been deeply unpopular.

As to McClernand his other problem was he was a Democrat serving a Republican administration. Unlike Logan and Butler, he stayed a Democrat and campaigned for McClellan in 1864. As the war went on Democrats found themselves shelved. While the reasons varied case to case, it was understood that Democrats who did well would have better political prospects.

As to McClernand’s personality, he was boastful, presumptuous, and intriguer, which strained his relationships. Tactically he was nothing special and I think corps command was above his abilities. On the plus side he was brave (even his detractors admitted that), good at administration, and a hard marcher. Of all the political generals, he possibly did the most for recruitment. Also, considering he served with men who hated him, McClernand was a better team player than most men in a similar circumstance. As noted, he fully backed Grant’s April-May drive on Vicksburg, and had recommended the plan that ultimately worked. He also supported Grant after his removal in February 1862, although by then it was clear the pair were no longer friends.

Grant hitched his star to Halleck? What choice did he have? Halleck was his superior officer from the departure of Fremont until Grant was promoted to Lt Gen.

When did Halleck try to get rid of Thomas?

Grant could in theory have asked for a transfer or intrigued against Halleck in1862. Many other officers did so for lesser insults. Halleck tried to remove Grant several times in early 1862, and of course after Shiloh made Grant irrelevant, relying more on Pope during the siege of Corinth. Grant though stayed loyal, and it paid off.

Grant was a master of army politics and I think this needs more attention. Joe Rose in Grant Under Fire holds that against Grant, and I understand why. I by contrast think it is one of his greatest strengths. Same with Halleck as well. He too was a master of the game, but he lacked Grant’s military abilities.

Halleck tried to remove Thomas in December 1864. But unlike with Hooker, who he detested, he was not willing to go all out and remove him without the full backing of Stanton, Lincoln, and particularly Grant. He wanted Grant to do it and it was nearly done. Fortunately, the telegraph operator waited because the line to Nashville was down. When it resumed the first messages were of a sweeping victory. in 1865 when Thomas met Stanton, he was introduced to the operator, with Stanton saying “here is the man who saved your career” (to paraphrase).

This is in reply to Mr Chick. Thank you for your reply, but I have to disagree with all three of your paragraphs above.

Grant was a subordinate to Halleck, and we know the options he considered in ’62. Continue to do his duty, or resign. Nothing about intriguing against Halleck. I think its a mistake to characterize a good subordinate as “hitching to the star” of their superior. In the military, it’s simply considered following orders.

I have the Rose book, but don’t share your regard for it. In fact, I’m not sure his “expose” even belongs in a non-fiction section. When it came to playing politics, I don’t see Grant as all that accomplished. Did he ever jump the chain of command, like McClernand and Rosecrans, going straight to Lincoln for some career favor? Not that I remember.

I don’t think that anyone in Washington in Dec ’64 really wanted to sack Thomas. They wanted him to attack. That was the whole issue.

Allow me to elaborate on a few points.

To understand how Grant interacted with Halleck, his subordinates, and how he played the game, I would recommend the dissertation “Grant’s Lieutenants in the West.” The gist is if Grant knew that Halleck liked a particular officer, he befriended them. If he knew Halleck did not, then he mistreated them. One of the only exceptions to this was Grant’s sadly short friendship with W.H.L. Wallace. It was a splendid strategy. In that way Grant “hitched his star” to Halleck and earned his trust over time.

Grant showed great skill at army politics. He cultivated his friends, punished his rivals (real and imagined), and was friendly with reporters. He also early on gained the support of Washburne and Yates, who were both allies of Lincoln. Grant did not need to write to Lincoln before Vicksburg. Washburne did it for him, which had the benefit of making Grant appear “non-political.” Rosecrans by contrast had no political allies close to the president until after Stones River, when he earned Chase’s favor. Even then, Chase and Lincoln had a strained relationship. Washburne was Lincoln’s fried and he trusted Yates. Those were better allies to have than Chase.

Another stroke of genius was cultivating Logan and McClernand in 1861. Being that Grant was in Cairo, he knew their support was needed. Other commanders often failed in this regard (Buell practically face-planted), so I see it as one of Grant’s strengths.

As to Rose, my research in Fort Donelson and Shiloh has only strengthened my trust in his work. Looking at the sources in those two battles, he is pretty spot on. You may disagree with Rose, or not like his style, but the research is good. It demands honest counter-arguments, which I have given him on a few points related to Fort Donelson, Shiloh, and particularly Sherman. I encourage all of Grant’s many admirers to take up the debate, and not to dismiss him out of hand.

I have written the upcoming ECW title on Nashville (delayed as all things due to covid) and your assertion is not supported by the correspondence I have read. Grant disliked Thomas. Not as much as Rosecrans, Granger, McClernand, Prentiss, or even Wallace, but enough to where he saw Thomas’ justified inaction as an excuse to remove him. The orders were written to remove Thomas, even after Stanton and Lincoln soured on it a bit. Only the telegraph operator stopped them from going through. In Grant’s career, it was a low point, but unsurprising. Perhaps Grant’s greatest personal weakness was his pettiness.

As to any assertion that Thomas could have attacked before December 15, he lacked the cavalry to do so in such a way to keep up a sustained pursuit after the battle. Once he did have his cavalry massed, the weather went bad. He attacked the very moment the weather improved, and proved all of his doubters wrong. Even then though, Grant advised he not be promoted and then reduced his command in January 1865. To Stanton’s credit, he ignored Grant and promoted him anyway. To Sherman’s credit once the war was over he secured for Thomas a plum assignment. On that last point I am sure Rose will disagree, but I think the Sherman/Thomas relationship is much more interesting and complicated than most people realize.

We’ll just have to disagree then. Grant was not that adept at army politics and he didn’t go out of his way to cultivate reporters and other advocates.

The alleged bad feelings between Grant and Thomas is one of the most overstated nothingburgers of the war.

Rose’s sections on Donelson and Shiloh are among the most skewed and false. It speaks volumes to me when a writer brings up Rose, and not Simpson or any other more respected work on Grant.

I’m familiar with a book reviewer’s criticism of a past book of yours, and I get the impression that this new book is going to suffer from the same shortcomings, specifically anti-Grant and pro-Beauregard bias.

Sherman and Thomas were both at West Point at the same time.

Sherman and Thomas were both at Bull Run and both were promoted after the battle.

Sherman and Thomas both went to KY to build the Army of the Ohio.

Sherman assumed command of all forces including Thomas after Anderson resigned.

Sherman was replaced by Buell and Sherman went to MO directly under Halleck.

During Grant’s Donelson campaign Sherman ran Grant’s supply operation from Paducah, KY.

After Donelson, the Confederates retreated tp Corinth, MS to get enough supplies for their army.

Sherman went upstream to Pittsburg Landing and took over when Smith died of infection. Sherman organized the camp at Shiloh.

Halleck began concentrating troops at Shiloh for a campaign against Corinth.

Buell marched from KY to join Halleck. Thomas followed Buell and arrived at Shiloh after the battle.

The Confederates attacked at Shiloh before Halleck arrived (Halleck did not want any battle before he arrived). Halleck took command when he arrived on the field after Shiloh.

After Corinth, Thomas remained with Buell and then Rosecrans in TN.

Halleck went to DC and Grant assumed his command.

Sherman went to the Mississippi where he became part of Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign.

After Chickamauga, Thomas replaced Rosecrans commanding the Army of the Ohio. Grant assumed overall command of the western theater and had Sherman make a tortuous march from Mississippi to Chattanooga to combine enough force to defeat Bragg.

At Chattanooga, Sherman’s attack on the Confederate right flank of Missionary Ridge was stalled because his position was separated from Missionary Ridge and Confederates could reinforce their right and the terrain prevented Sherman from flanking. This is when Thomas’s troops stormed up Missionary Ridge to rout the Confederates.

Grant then went east to command all armies and Sherman commanded in the West under Grant. Thomas was under Sherman and McPherson assumed Sherman’s command. Sherman was in constant communication with his commanders including Thomas throughout the Atlanta campaign. McPherson’s force was the most mobile, traveled light and was used for flanking. Thomas’s army was more heavily burdened and was typically in front of the Confederates.

After Atlanta, Sherman sent Thomas along with the rest of the least mobile parts of his army to Nashville. Hood was unattached to any base and constantly trying to cut the railroad from Nashville to Atlanta.

From Nashville Thomas could easily be supplied by river and block Hood from moving north. Atlanta was worth nothing to the union, and its value to the Confederates as a rail and supply center was destroyed by Sherman.

Sherman marched to the sea and was out of contact with Thomas until he reached Savannah GA.

So the main contact between Thomas and Sherman was in KY where Sherman was in charge, but Sherman was in Louisville and Thomas was always south and east. They had the most interaction during the Atlanta campaign. Much of the correspondence between Sherman and Thomas is preserved in the military communications.

Official records can be found in: “The War of the Rebellion”

https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records

or http://collections.library.cornell.edu/moa_new/waro.html

Sean@ I’m interested in the dissertation you mentioned. Do you have a pdf available?

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Generals-Grant-and-McClernand-Cairo-1861.jpg Above link to image of Brigadier Generals U.S. Grant and John A. McClernand on steps of the Cairo Illinois Post Office in late 1861 when the two were friends, plotting how to win the war.

Because I believe it has relevance to this discussion, the following is added:

“On the face of it, the successful politician, McClernand, ten years more senior, with origins in a Southern state, and with limited experience as a Private during the Black Hawk War, has little in common with the West Point trained, but struggling since his resignation from the Army, Grant. And there does not appear to have been any pre-Civil War contact between the two men (Grant lived in Missouri until 1860) so it is safe to assume that their first encounter occurred June 1861, when finally-a-Colonel Grant permitted Illinois Congressmen Logan and McClernand to address his 21st Infantry Regiment outside of Springfield [Memoirs pages 244 – 5].

The next meeting between Grant and McClernand appears to have taken place after the Disaster at First Manassas, after McClernand had been granted permission to raise his brigade of infantry regiments (and was accorded rank of Brigadier General, junior to Brigadier General Grant.) The relationship appears to have evolved as a “friendship of convenience.” Grant needed assistance in his seniority dispute (September 1861) with Benjamin Prentiss; and McClernand – recently arrived at Cairo – was available to take command of in-arrest Prentiss’s troops in Missouri (this arrangement was suggested by Grant, but not actioned by Fremont – see Papers of USG vol.2 pages 173 – 4). With Prentiss out of the way, Grant relocated to Cairo and established his Head Quarters, District of S.E. Missouri (and benefited from Brigadier General McClernand’s presence when the opportunity to occupy Paducah presented on September 5th). While Grant took the 9th Illinois and 12th Illinois to Kentucky, McClernand remained behind with his brigade and provided defense of Cairo.

Upon return from Paducah, about September 7th, District commander Grant and Post of Cairo commander McClernand had ample time to get to know each other (Grant would remain at Cairo until 21October) and during that time the communications between the two generals is cordial, supportive and frequent… in keeping with a letter sent from McClernand to U.S. Grant dated September 4th: “I will be happy to co-operate with you in all things for the good of the service” (Papers of USG vol.2 page 184). No doubt during this period of close interaction, fellow Democrats Grant and McClernand would have shared “war stories” and may have realized their similar experience as “dispatch riders” (Grant at Monterey during the Mexican War and McClernand during the recent Bull Run Campaign.) McClernand would also have details of that campaign (and Irwin McDowell) not available anywhere else.

From the tone and content of the communications, it appears that Grant was “grooming McClernand to become the best Brigadier he could be” (see Papers of USG vol.2 pp. 184 – 353 and vol.3 pages 67, 88 and 123 – 125). Reports were requested by Grant, the preparation for movement of troops ordered, recommendations provided for establishment of Provost Marshal and other measures (at all times with Grant addressing McClernand as “General” or “Gen.”) The hands-on training with Grant in close proximity culminated with Grant’s brief departure on October 21st for a visit to St. Louis, leaving McClernand in acting-command of the District HQ at Cairo (Papers of USG vol.3 page 67). McClernand obviously passed that test, for on Grant’s return to Cairo he began planning for the Observation of Belmont (and put McClernand to work in helping organize transport and equipage for that expedition – Papers USG vol.3 pp. 98, 103 and 108 – 109).

Papers of US Grant vol.3 pages 123 – 126 details the final preparations and orders for the Expedition against Belmont (with Brigadier General McClernand’s given pride of place as lead brigade.) Following successful completion of the raid, General Grant provides a glowing report of McClernand’s participation (page 142) and McClernand’s own report of Belmont can be read: Papers of US Grant vol.3 pages 196 – 201.

After Belmont, General Grant next left McClernand in acting-command District HQ on November 18th when Grant departed on an inspection tour of Bird’s Point and Cape Girardeau and the frequent communications between the two generals remain cordial and supportive through early February 1862.”

Compiled by Mike Maxwell July 2018.

Good addition

Cairo was crucial to the union war effort. The union was building iron clads at Cairo that would allow them to control the Ohio River. Grant saw the opportunity for amphibious operations. Grant was pushing Halleck to approve an expedition up the Tennessee and Columbia Rivers to Capture Forts Henry and Donelson. At first, Halleck was reluctant to sign off. At some point McClernand would have been informed by Grant about the campaign. After Thomas victory at Mill Springs, Halleck was in favor of an offensive along all fronts. The forts on the Mississippi were too heavily guarded to attack directly and in early January Halleck approved the expedition against Henry and Donelson, the center of the Confederate line. By mid January, Grant was using the iron clads as protection to ferry troops across the Ohio River (good practice for the coming amphibious operation). Grant had sent CF Smith on an iron clad to scout Fort Henry, Smith reported that Henry was weakly defended. On Feb. 4 1862, Grant with McClernand’s division landed 3 miles from Fort Henry. Smith’s Division was to follow and Halleck was sending all spare troops to the effort, with Sherman in charge of supplies at Paducah, KY.

This is how the friendship between Grant and McClernand came unstuck…

Although attributed to U.S. Grant, the Conquest of Fort Henry on 6 FEB 1862 was accomplished by Naval Officers and crew aboard timberclad and ironclad gunboats, enduring hits by powerful artillery and contact with torpedoes that failed to detonate. With Confederate guns knocked out of action and the Rebel Flag lowered, a boat from the Flagship rowed inside the flooded Confederate fort, transported rebel BGen Tilghman back to the Flagship, and Flag-Officer Foote took the surrender.

Newspapers of the day immediately proclaimed, “Fort Henry Surrenders” and “Splendid Naval Victory” [New York Herald of Saturday 8 FEB 1862 page one.] One can only imagine the response of Henry Halleck to “the Navy’s Victory.” (“Where was the Army?” springs to mind.) The problem was the weather: the same relentless rain that raised the Tennessee River sixty feet also turned roads required for use by infantrymen into slippery slop. General Grant ordered the infantry and the Navy to advance AT THE SAME TIME (11 a.m.) and the Navy arrived in range and began bombarding nearly two hours before the Army was close enough to offer assistance, or prevent escape of the majority of the Confederate garrison. Someone was responsible for “non-pursuit of the fleeing garrison,” and obviously that man… was John McClernand. Trouble was, McClernand did not realize how the Army’s political game was played; that the supreme commander was not to be held responsible for “embarrassing outcomes.” BGen McClernand wrote a glowing report detailing his struggle to reach the fort after “starting at the time ordered.” (Meaning: “It was not ME that started the First Division forward too late to accomplish much.”) [OR 7 page 129.]

General Grant had promised to move on Fort Donelson on 8 FEB, but the rain-affected roads connecting Fort Henry to Fort Donelson remained impassable.

10 FEB: In the afternoon a Council of War was conducted by BGen Grant, through which he hoped to garner consensus of his senior officers to initiate the movement on Fort Donelson. All were in favor, and briefly stated as much… except BGen John McClernand. As reported by fellow attendee, Lew Wallace, “General McClernand took the opportunity to read a paper [before the assembly] outlining in detail his suggestions for the proposed advance… to the apparent displeasure of General Grant” [Papers of USG vol.4 page 184.]

Grant ordered the movement east, to commence IAW General Field Orders No.12 [Papers of USG vol.4 pages 192 -3] Wednesday morning 12 FEB at earliest hour possible. McClernand had already begun moving elements of his Division east, perhaps five miles, on 11 FEB (possibly in reaction to earlier defective orders issued prior to Fort Henry.) [OR 7 page 170.] In McClernand’s report on Fort Donelson he brags about “starting east earlier than ordered.” [This early movement may have had benefit, as Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest was ordered west “to observe the enemy” and found them so near Fort Donelson there was no opportunity for a delaying action west of the fort.]

14 FEB: McClernand advised Grant that he did not have sufficient troops to continue his line south and east of Fort Donelson to the river (or to a deep tributary feeding the Cumberland River.) [OR 7 page 175 and McPherson’s report page 162.] Grant did not provide the necessary troops until well after sunset, when it was too dark to make out the lay of the land (forested swamp with knee deep standing water; and snow falling with temperature near freezing.) McArthur was positioned further west than ideal, allowing a corridor that Forrest found and exploited early next morning during the breakout attempt. [OR 7 pages 217 Chetlain report; 215 McArthur’s report.]

16 FEB: Grant blamed McArthur and McClernand for the near fatal breakout action of the Confederates on 15 FEB (though Grant himself was away from his army, some miles to the north when the incident occurred; and claimed to have “returned late morning” when his actual return was about 2 p.m.) After the Surrender of Fort Donelson, McArthur’s and McClernand’s men were lodged outside Fort Donelson in the melting snow without tents and assigned onerous details (so menial and punitive that McClernand wrote a Letter of Complaint – see OR 7 page 634 General Orders No.4 and Papers of USG vol.4 page 242 and 242 notes for Letter of McClernand.)

19/20 FEB: Following the capture of Fort Donelson, McClernand was taken to Clarksville (because he was friendly with Congressman Cave Johnson, and it was believed McClernand could smooth the way to Union occupation of Clarksville.)

24/25 FEB: With some of his most loyal supporters, Grant took advantage of the arrival of Bull Nelson’s Division aboard 7 transport steamers to “return that force to Buell” …and Grant went in company, remaining aboard towboat W.H.B until 27 FEB. McClernand was taken along (possibly because Grant felt it was safer than leaving him at Clarksville – “Keep your enemies closer.”) After the unauthorized visit to Nashville, during which MAJOR General Grant lorded it over Brigadier General Buell, word of the trip to Nashville leaked out, and Grant was certain it was McClernand who did the leaking. Before the end of February 1862 the “friendship” between Grant and McClernand was well and truly at an end.

But when one door closes, another door opens…

15 FEB [Papers of USG vol.4 page 215] Letter of Fealty from W.T. Sherman to U.S. Grant: “If there is anything I can do for you, just let me know.”

It’s worth reading Lew Wallace’s account of Henry/Donelson in full. McClernand does not come out looking good. In addition to failing to hold the road at Donelson, McClernand seemed incapable of leading the counterattack to retake the road with elements of all three divisions. He was done. Defeated.

Lew Wallace also describes how McClernand took excessive credit in his official report. “All he plausibly can he appropriates to himself.” Grant noted the embellishments as well. McClernand was also writing to Lincoln during this period with exaggerations of his successes.

Grant did not “lord” his rank over Buell at Nashville. That is a Rose fabrication, or at least that’s the only book I’ve seen claim it. Not only is it out of character for Grant, but it’s unsupported and in fact, self-refuting. If Grant was the “lording” type, the command arrangement on the second day of Shiloh wouldn’t have been so deferential to Buell’s pride. One of the two men was definitely stiff, arrogant, and “lording,” but it wasn’t Grant.

One interesting item is that the compilation, Home Letters of General Sherman, omitted the beginning sentences of the letter in question, sentences which just happened to be somewhat critical of General Grant: “I got your letter from Cincinnati and am glad I did not misjudge you in Supposing you had too much sense to come down here on a wild goose errand—Mrs. Grant came down & poor Grant had to make so many & such antic apologies that even his wife must have been mortified—it will be quoted as one of the many pieces of evidence that he did nothing at Vicksburg & meant to do nothing, for I see in the horizon the first faint clouds that threaten Grants fair fame and history. Well, though I would rather See you than any one on earth, I say honestly & truly you did right not to come—indeed it would have been wrong to come—I will escape from the popular pen in which a supposed virtue & patriotism caught me along with others as soon as decency will permit & it may be in some safe place we may enjoy peace & each others society whilst the factions of a Demagoguism tears our Dear People to pieces. The Noises & clamor have produced their fruits. Even Grant is cowed & afraid of the newspapers.”

The letter helps confirm Sherman’s rather tentative grasp of strategy (in putting his faith in an overland drive from the north on Vicksburg, as opposed to crossing the Mississippi below that city; “this whole plan of attack on Vicksburg will fail must fail”); his petulance; and his gross untruths regarding McClernand. Sherman’s threat of insubordinate conduct, “I will not serve under McClernand,” had already been preceded by actual insubordination when he told Grant: “I only fear McClernand may attempt impossibilities … I think you might safely join us and direct our movements.”

Dan,

I didn’t find the word, “lord,” used concerning this episode in Grant Under Fire. Are you sure of your quote?

In Larry J. Daniel’s Days of Glory: the Army of the Cumberland, 1861-1865, on Page 71: “Grant made an unannounced and totally unauthorized visit to Nashville” … “Accompanied by a bevy of correspondents …” “Upon the heels of his great victory, Grant acted cocky. The incident unquestionably resulted in strained relations between the two generals, and even Halleck was angered by Grant’s blatant crossing of jurisdictional lines.”

Arriving at Nashville, Grant didn’t go to where he knew Buell was, but toured the city of Nashville instead. He signed himself Major-General in his note to Buell, but went back to signing Brigadier-General later. This note, referring to “Headquarters District of West Tennessee, Nashville” and “U. S. Grant, Major-General, Commanding” indicated that Grant’s Headquarters were in Nashville and he was in command. That accentuates the cockiness.

Mr Rose, the word “lording” belongs to Mr Maxwell, but the misrepresentation is from your book, where you write that Grant’s “overbearing attitude, insulting message, and the trip itself… poisoned the relationship between the two generals.” You claim that he was “testing out his new grade,” and that he wrote a “stiffly-worded letter.”

Like so many other bad interpretations in your book, this would have been out of character for Grant.

No doubt he was feeling cocky after the recent victory, and wanted to immediately go further, but the rest is fiction.

Because the issue of “Appointment to Major General” has been raised:

Henry Halleck referred to Grant as “Brigadier General” until March 1862.

Papers USG vol.4 p.236 17 FEB 1862 Grant refers to self as BGen [Comm. To Hurlbut]

Papers USG p.248 19 FEB BGen Grant in Letter to Cullum

Papers USG p.270 22 FEB BGen Grant in comm to McClernand

Papers USG p.271 22 FEB Letter to Julia “I see in the papers, and also from a dispatch sent by Mr. Washburn that the Administration have thought well enough of my administration of affairs to make me a Maj. General.” [Note: “Notice in a newspaper” or “heard it from a friend” was not enough to promote a Civil War Union Volunteer to General Officer rank. The steps were these: 1) The man must be Nominated to the higher rank ( MGen Halleck or President Lincoln contacted Secretary of War Stanton); 2) Congress confirmed the appointment; 3) Secretary of War (or President of United States) signed the appointment; 4) The War Department confirmed receipt of the appointment (with date of receipt/ date of publication of War Department General Orders the EARLIEST that the officer could assume the new rank); 5) The Commanding Officer of the man to be promoted notified that man of his Offer of Promotion. That new Major General had to a) accept the promotion; b) sign documents acknowledging that acceptance (and awareness of benefits and responsibilities, area of operation of the new rank); c) sign a document for pay office, informing Pay Department to pay the officer at the rate of Major General; d) sign the new “Loyalty Oath to the U.S. Government” [it is unknown if this last was required of U.S. Grant in FEB/ March 1862, but steps a, b & c were required.] 6) Having signed the paperwork and accepted the promotion, the Commanding Officer congratulated the new Major General on his promotion, to take effect from THAT moment (even though it may include a back-date to February 16th.) [See Papers of U.S. Grant vol.4 page 272 for further details of above.]

Papers 23 FEB BGen Grant in comm to BGen Cullum [Grant still refers to himself as “Brigadier General” because he has not been officially promoted to higher rank of Major General of Vounteers.]

Papers p.277 24 FEB BGen Grant signs General Orders No.10

Papers p.282 24 FEB BGen Grant meets Bull Nelson and signs order to BGen Nelson, returning that man and his Division to the Army of the Ohio.

Papers p.282 (note) Captain Hammond (Sherman’s AAG) signs Special Orders No.32 of 22 FEB to BGen Nelson, directing Nelson to report to Major General Grant. [Hammond was in error with use of the MGen prefix as Grant had not accepted official promotion as yet.]

Papers p.289 25 FEB BGen Grant sends letter to BGen Sherman

Papers p.293 27 FEB Grant signs comm to BGen Buell as Major General Grant

Papers p.294 28 FEB BGen Grant comm to BGen Cullum

Papers p.298 28 FEB Letter of Colonel WHL Wallace to his wife, describing “the trip to Nashville” and includes most of the participants on that trip.

Papers p.301 1 MAR BGen Grant comm to MGen Halleck

Papers p.307 2 MAR Colonel C.C. Washburn (brother of Congressman Washburne) arrived at Fort Donelson from visit to Halleck at St. Louis and delivered Grant’s official offer of promotion to Major General. Grant accepts and signs the paperwork. As his first official act as Major General, Grant appoints Colonel Washburn as ADC on his Staff.

As regards Grant’s use of the title “Major General” when referring to himself in Nashville, there are only two explanations: Brigadier General Grant used the title in error, accidentally; or Grant used the title intentionally.

If Grant used the title accidentally, one would expect to see continued use of “MGen” after departure from Nashville; but such is not the case. Therefore, one can assume that the title was used intentionally (as evidenced in at least one communication with, Don Carlos Buell. Would be interesting to learn if “MGen” Grant forced BGen Buell to salute him, as well.) In support of this assumption, Grant ordered the Second Division under Brigadier General C.F. Smith to report to Nashville, despite communication from his boss, Major General Halleck “to not send troops belonging to Grant’s command east of Clarksville.” [Supposedly, “MGen” Grant convinced Buell, or acceded to Buell’s claim that “Buell needed those extra troops to defend Nashville.”] [Memoirs of US Grant vol.1 pp.262 – 265.]

Based on the above, this writer concludes that U.S. Grant “lorded it over” Department of the Ohio commander Buell; made use of rank and seniority to which he was not yet entitled.

CF Smith was requested by Buell to come to Nashville. And Grant notified HQ and forwarded copies of Buell’s request. See letters to Cullum on Feb 28th (PUSG 4:296) and to Kelton (same volume, page 298)

Also, it should be noted that the Senate confirmed Grant’s promotion on Feb 19th, the same day Washburn notified Grant.

So there is no real evidence presented here that Grant “lorded” his rank over Buell. Just assumptions.

It has been claimed that “it was out of character for U.S. Grant to lord his rank over Buell, or anyone else.” Let’s review the record:

April 1861: As war preparations and recruiting get underway in Galena Illinois, newly arrived Ulysses S. Grant, co-operator of a Leather Goods Shop, is introduced as “Captain” Grant. Grant has been out of Government employ for six years; and has no intention of commanding the Company of Galena troops subsequently raised. He does not “set the record straight,” but allows the use of “Captain Grant” in subsequent meetings, including with the Governor of Illinois, Richard Yates, in May 1861.

Late July/ early August 1861: Colonel Grant of the 21st Illinois disputes the seniority of Colonel Turner of the 15th Illinois [both men are Colonels of Volunteers, and Turner received his commission as Colonel a few weeks ahead of U.S. Grant.] Colonel Grant sent an order to the 15th Illinois “requiring they clean the camp of the 21st Illinois.” Colonel Turner was away when the order arrived; LtCol Ellis received the order, “read it, his face burning with anger, and sent word to Colonel Grant that his regiment did not enlist for the purpose of doing the dirty work for his, or any other regiment.” LtCol Ellis and Colonel Grant soon met face to face: Ellis refused the order; Grant had him Court-Martialled (but the 15th Illinois did not clean the camp of the 21st Illinois) [Army Memoirs of Lucius W. Barber (1894).] And as result of “exerting his rank” Colonel Grant took command of the two-regiment brigade and began his climb to higher positions of authority within the Volunteer Army.

17 AUG 1861: U.S. Grant “heard it from a friend” that “he is to be the Senior Brigadier General from Illinois.” He begins calling himself “Brigadier General” Grant and on this day he encounters Brigadier General Benjamin Prentiss at Ironton Missouri. BGen Prentiss has been commanding a brigade of Illinois troops since his appointment by Governor Yates as Brigadier General on 8 May 1861. Prentiss presented Grant with his orders [to take command of all troops in vicinity of Ironton] and “BGen” Grant refused the order, claiming HE (Grant) was the senior man of the two (based only on “I read it in a newspaper.”) Further, Grant “refused to subjugate himself to a junior officer” [Memoirs of US Grant vol.1 page 208.] Neither man had documentation of their Date of Rank; but Grant claimed “he was informed he was the senior Brigadier General from Illinois.” Grant refused to serve under Prentiss, so he boarded the next train and returned to St. Louis (and complained to MGen Fremont about the situation.) A few days later, the U.S. Army General Orders No.62 dated 20 August reached St. Louis: all of the Brigadier General appointments from Illinois, as confirmed by U.S. Senate, had a date of rank of 17 May 1861; and first on that List… John Pope. [U.S. Grant was second, behind Pope. And Benjamin Prentiss had his 8 May date of rank arbitrarily adjusted to 17 May, putting him fourth on the List, behind Stephen Hurlbut.] Armed with this information, Grant “met” Prentiss on September 1st near Cape Girardeau and presented new orders, signed by Fremont, giving Grant command of all troops in vicinity. Prentiss refused to believe that “someone who was not even in the Army on the 8th of May” could somehow become senior Brigadier General; Prentiss tendered his resignation and returned to St. Louis under arrest. And BGen Grant took command of all U.S. troops in Eastern Missouri (and made arrangements for BGen John McClernand to take over command of Prentiss’s brigade, though that did not eventuate)[Shiloh Discussion Group topics “Ex post facto” and “Special Orders No.141.”]

27 FEB 1862: U.S. Grant, calling himself “Major General” Grant is in Nashville and lords it over Brigadier General Buell. Before Grant’s promotion to Major General (which occurred 2 March 1862) Buell is the senior Brigadier General of the two officers, ten places ahead of Grant on the List.

In addition to above:

Papers of US Grant vol.2 pp.132 – 133 communication of US Grant to Lorenzo Thomas, Adjutant General of U.S. Army at Washington D.C. dated 25 AUG 1861: “No official notice of my appointment [to Brigadier General] has ever reached me… I would therefor respectfully request an official notification, and if it can be furnished, my relative rank with others of the same grade.”

Mr. Maxwell,

Thank you very much for the information about promotions and for providing good evidence that Grant’s use of the title major-general was intentional. As he went back to being called brigadier-general afterward, the logical conclusion is that Grant was trying to put Buell down. That wasn’t the only cause for criticism of General Grant.

Grant abandoned his army and traveled to Nashville, outside of his own district and without his superior’s authorization. Among the individuals who indicated that Nashville was in Buell’s department were James B. Fry, Stephen Douglas Engle, John William Burgess, T. Harry Williams, and Jack H. Lepa.

Although Grant stated that the reason for the trip was to consult with Buell, his actions belied his words. Instead of trying to locate Buell and report to that department commander, Grant spent the day touring the city. He didn’t appear to be accomplishing anything military. The actual, rather brief, meeting with Buell only took place when Grant was heading back downriver.

Grant certainly had a better grasp of strategy than Buell, at least according to versions written by his supporters.

Grant’s undue actions poisoned his relationship with Buell, and this had unfortunate repercussions during the Battle of Shiloh.

Wow, having his former military service acknowledged with “captain” is somehow lording his rank?

The article was about Sherman and McClernand, so I won’t contribute to the Grant tangent any longer, except to say a little about this style of hit-job history by the author Rose, and his acolytes who’ve “hitched their star,” as Mr Chick would say.

The author who comes to my mind when Rose is mentioned is Thomas Dilorenzo. What Dilorenzo is to Lincoln, Rose is to Grant. They both use the same methods of mining and sifting through sources, and then presenting skewed interpretaions. The intent is the same: To tear down some historical figure for their own agenda. These expose-type books are not about historical truth. As Mr Chick has said, Rose admitted to throwing everything at the wall to see what would stick. Truth was not the priority. Only whether it would “stick.”

Just as hagiographical myths can last long after they’re refuted, so can negative myths. McFeely made questionable claims in his Grant book, and was criticized by other historians, and yet those claims are still repeated by Rose and others, including Mr Chick. And example of McFeely’s distortions would be the racist allegations against Fred Grant at West Point.

I believe this is the intent of Rose and his efforts to make negative attacks “stick.” To chip away at Grants historical reputation with charges that linger, regardless of being true or not. Mr Maxwell obviously shares in this purpose.

My hope is that ECW does not encourage or provide a platform for Rose’s specious attacks. It would be no different than bringing Dilorenzo on as a Lincoln scholar.

I have never “admitted to throwing everything at the wall to see what would stick. Truth was not the priority. Only whether it would ‘stick.’”

I have never felt that way nor do I write in that manner. Instead, I closely investigate the many controversies in which Grant’s defenders ignore, minimize, or deny his mistakes and weaknesses.

And, as to the supposition that Grant hadn’t the personality to act overbearingly toward Buell, even Grant’s staunchest defenders agreed that he readily indulged in vindictiveness, cronyism, pettiness, and implacable hatred.

One of the themes of Grant Under Fire is that Grant waged a personal war, to the detriment of the Union’s military efforts.