David Laird and The Christian Commission at Gettysburg

My ongoing work about Camp Letterman General Hospital and the treatment of the wounded following the battle of Gettysburg tends not to be the most uplifting work. Though stories of resilience and healing are common, so too are stories of death. Sometimes, however, even a story of death can give insight into the fears and strength of the wounded. The story of one Michigan Private illuminates the brutality of Civil War wounds, the worries of a wounded soldier, and how Victorian culture grappled with the idea of death far from home.

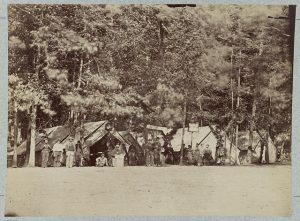

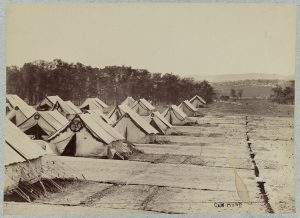

The United States Christian Commission was a private organization that followed the Union army in order to both provide physical goods and assistance as well as to improve their religious lives. For example, nurse Sophronia Bucklin recalled that at Camp Letterman the organization did their work “nobly,” and remembered a woman from the Christian Commission would take a wagon to the countryside daily and return with “generous gifts of fowls, eggs, milk and butter.”[1] In addition to distributing food and clothes, they would gift bibles or prayer books as well as lead religious discussions. Though sometimes criticized by a similar secular organization, the United States Sanitary Commission, for focusing on religious conversion over physical assistance to the dying, they did good work. Their physical and spiritual comforts were of great help to suffering wounded at the hospital, whether Union or Confederate. In this chaotic aftermath, Reverend R. J. Parvin met one particular wounded man whose interactions stood out to him: Corporal David C. Laird.

Laird served with Company A of the 4th Michigan Infantry. At age 19, he left his occupation at his parents’ farm to join the army on June 20, 1861.[2] He served for over two years, fighting at battles such as Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. His luck ran out at Gettysburg. On July 2, 1863, the regiment was thrown into the maelstrom of the Wheatfield and under fire on both front and flank. Of 403 men, 165 were casualties, including Colonel Harrison Jeffords, who was mortally wounded in a melee attempting to save the regimental colors. During this desperate withdrawal, Laird fell to the ground dangerously wounded.

His wound was bad. In the Camp Letterman Case Ledger, his injury was listed under fractures of the spine and described as caused by a Minié ball “entering the lumbar region one inch to the left of the spine, passing downwards and forwards to the right side fractured the transverse process of the fourth lumbar vertebra and emerged near the right Ilium.”[3] He was transferred to that hospital on July 31 after previous treatment elsewhere. Staff noted, “July 31st General health good. The discharge from the wounds is profuse. He experiences great difficulty micturition[passing urine], and the urine is streaked with pus.”[4] His case only got worse. The record continued: “Aug 7th several Spicula removed. Aug 10th Lanced a large abscess in the right lumbar region. Aug 20th Discharge increased and his health failing.”[5] In summary, the bullet had missed the spine itself but then damaged vertebra while passing through his body as well as likely damaging other organs. Surgeons had removed bone fragments and attempted to control the discharge but were facing a losing battle.

Throughout this, Reverend Parvin repeatedly met with Laird to offer comfort. Parvin wrote: “I found on the field a Michigan soldier named David Laird, and visited him regularly while I was at Gettysburg. . . .At first he was very much troubled because his wound – a serious one received while the regiment was falling back under orders – was in the back.”[6] Laird was concerned about the nature of his wound. Having been shot in the back, he feared others would deem him a coward as it might appear he had fled from battle. Parvin wrote letters on Laird’s behalf to his family explaining the situation. A letter from Laird’s father helped to assuage those fears, stating “As to David’s wound in the back, it need give him no uneasiness. None who know him will suppose it to be there on account of cowardice.”[7] With this news, Laird could be certain neither his friends nor his family doubted his bravery. Key to Parvin’s account, however, was Laird’s spiritual health. The prelude to the story stated, “The most precious reward to the Delegate was the privilege of turning a wandering soul to Jesus,” and Parvin noted that his interactions with Laird included a story of the wounded soldier speaking “of his early training, of his wandering from it, of his longing to return.”[8] Laird had been raised a Christian, but strayed. Through long conversations and both physical and spiritual aid, Parvin was convinced that Laird had returned to religion. Though religion is always a contentious topic and Parvin’s works are far from impartial, it seems clear that this counselling comforted the soldier.

Despite assuring others of his bravery and a religious revival, Laird’s situation worsened. Parvin noted: “The weeks passed on; the pleasant September days came, but David was worse. His father came in time to see him die.”[9] The final entry in Laird’s medical record was as follows: “Sept 5th to 24th, Failing up to last date when Death occured[sic].”[10] He was buried in the Camp Letterman cemetery, and eventually moved to the Gettysburg National Cemetery, where he rests evermore in grave B-22 in the Michigan plot. Much of Laird’s story falls within the Victorian nature of the Good Death, a topic examined by many recent historians, notably Drew Gilpin Faust’s 2008 This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. Essentially, a Good Death involved commitment to religion and the presence of loved ones. Though many soldiers were denied this during the Civil War, the religious counseling of Reverend Parvin and the arrival of his father allowed David Laird to fit within this mold and have a more socially acceptable death than most others. Parvin’s account ends with him trying to comfort David Laird’s father and being told “I don’t need any comfort from man, for God has given me so much, in seeing the happy death of my boy, that I am perfectly content.”[11]

[1] Sophronia E. Bucklin, In Hospital and Camp: A Woman’s Record of Thrilling Incidents Among the Wounded in the Late War (Philadelphia, PA: J.E. Potter and Company, 1869), 153.

[2] Martin N. Bertera and Kim Crawford, The 4th Michigan Infantry in the Civil War (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2010), 315.

[3] Henry Janes, Camp Letterman Hospital Case Ledger, 1863, Special Collections, University of Vermont, transcribed by Jonathan Tracey, compiled and edited by John Heiser, Gettysburg National Military Park Library, 47.

[4] Ibid,.

[5] Ibid,.

[6] Edward P. Smith, Incidents Among Shot and Shell (Edgewood Publishing Company, 1868), 166.

[7] Ibid,.

[8] Ibid,.

[9] Ibid,.

[10] Janes, 47.

[11] Smith, 167.

Very moving. I would like to hear more about the commission. In our secular age, it is good to remember how much comfort and encouragement religion can provide.