On The Eve of War: Buffalo, New York

The morning sunrise on February 16, 1861, slowly turned the blanket of snow that covered Buffalo, New York, overnight into mud. Though the mud would only worsen by street walkers, horses’ hooves, and carriage wheels, Buffalo’s citizens knew they had to get out in it. They had work to do.

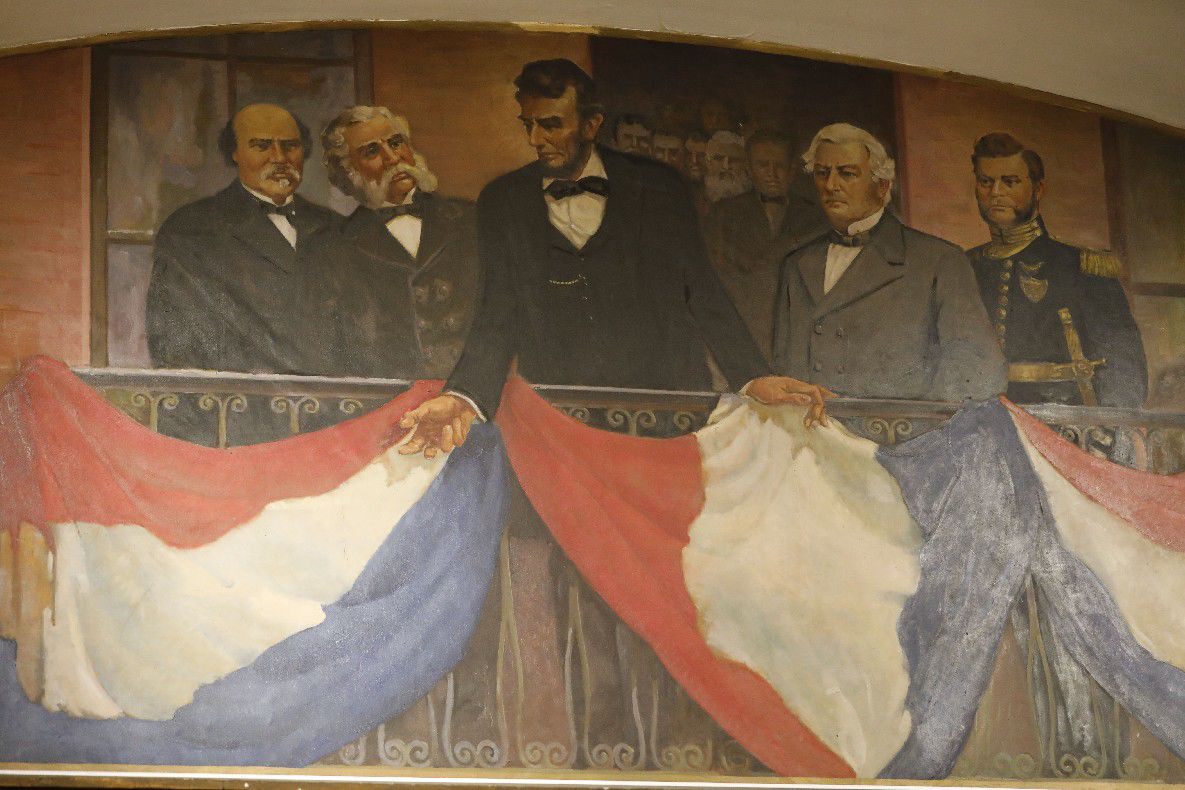

Some went to work tugging on ropes to raise the flag of the United States of America to the top of the city’s many flag poles. Others draped their homes and storefronts in the nation’s colors: red, white, and blue. Despite the growing quagmire in the streets and the temperature barely surpassing the freezing mark, crowds gathered beneath the fabric adornments to wait for the city’s long-awaited guest, president elect Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln’s trip east scheduled two nights in Buffalo at the heart of Erie County, a western New York locale he had to thank for helping him win the presidency. Sixty percent (81,129) of the county’s population of 141,971 lived in the city. Overall, Erie County gave Republican presidential nominee Lincoln a majority of its votes in November 1860.

Finally, after a long day of work, Lincoln’s entourage pulled into Buffalo by train. At 4:30 p.m., Michael Wiedrich’s artillery company blasted a cannon salute to the arriving Lincoln. A “swarming of humanity” clamored to get a glimpse of the lanky politician from Illinois. They “packed upon the walks, clustered upon the roofs, crowded at the windows,” said one eyewitness. The crowd was so eager to greet Lincoln that, when he departed from the train, it “became an ungovernable mob” and pressed upon the line of soldiers who guarded the path for Lincoln to take from the depot. A few soldiers forced their way through the crowd and safely escorted Lincoln, accompanied by Buffalo resident and former president Millard Fillmore, to their carriage. David Hunter, a member of Lincoln’s party, suffered a sprained shoulder in the disorder.

Lincoln soon made his way out of the crowd and into the muddy streets to the American Hotel. From the hotel’s elevated balcony, Buffalo’s mayor greeted him before the president elect stood before the crowd and spoke for a few minutes. Naturally, Lincoln thanked the crowd for their hospitality before delving into the “threatened difficulties to the country.” (By February 16, seven southern states had seceded from the United States.) In the present crisis, Lincoln implored the crowd in Buffalo “to maintain your composure.”

“Stand up to your sober convictions of right, to your obligations to the Constitution, act in accordance with those sober convictions, and the clouds which now arise in the horizon will be dispelled, and we shall have a bright and glorious future,” Lincoln continued. “When this generation has passed away,” he concluded, “tens of thousands will inhabit this country, where only thousands inhabit it now.”

Lincoln’s theme of progress no doubt resounded with Buffalo’s older citizens. In 1810, a visitor to Buffalo scornfully commented that it was noticeable only for consisting of “five lawyers and no church.” In 1824, before the completion of the Erie Canal, only 2,400 inhabitants populated the city on the shores of Lake Erie. Thirty-six years later, over 81,000 people lived there. The canal, the lake, and numerous railroads fueled the city’s growth.

Buffalo was also part of the burned-over district, a swath of western and central New York that hosted religious revivals as part of the Second Great Awakening. This religious fervor sparked social activism, also. Movements such as abolitionism and women’s suffrage gained traction in the religiously awake region.

Immigrants mixed into Buffalo’s growth and society. Germans comprised 40% of the city’s population. A smaller group of Irish immigrants lived in Buffalo, also.

Prior to the opening of hostilities on April 12, 1861, New York state’s second most populous city (and the country’s tenth highest) was well prepared to lend a hand in suppressing the rebellion of the southern states. Its rail and canal connections could facilitate quick movements of troops raised in the city. Buffalo’s large population itself ensured that many of its young men would march off to war.

When news reached the Queen City of Fort Sumter’s fall, it reacted quickly to President Lincoln’s subsequent call for 75,000 volunteers. “The Government must be sustained at all hazards,” crowed the Buffalo Morning Express. So many volunteers tried to enlist that Buffalo’s officials changed the mustering site three times to a more commodious space. Finally, they settled on the old Court House, which, remembered one soldier from Buffalo, “was instantly full, thousands waiting outside.” Only one hundred names made it on the initial roster.

Just two weeks later, four volunteer companies departed for Elmira to lend a hand in ending the rebellion. “Once more we appeal to our citizens to help the volunteers,” the Morning Express implored. “They need it. Six additional companies of 77 men each, must be organized before Buffalo has a regiment of it’s own. Turn in men and make a hard, tough, fighting regiment, such as Buffalo should furnish!”

By the end of the war, Buffalo contributed over 20,000 men to the Union war effort. Of that number, 4,704 of them were casualties during the conflict. Some of those hard, tough, fighting regiment that seemed fitting for Buffalo to send to the front included the 21st, 49th, 100th, 116th New York infantry regiments as well as Wiedrich’s Battery I, 1st New York Artillery, among others.

The “aerial sketch of Buffalo” dated 1858, featured at top of this wonderful article: “How did they get that?” Click on attached link and advance 18 seconds into YouTube post by Chubachus: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lGKMYUmgiFw

I might add the 155th Regiment, an all Irish regiment , in which my great grandfather Patrick and great Uncle John, fought. Patrick spent a year in Salisbury Confederate Prison and never recovered his health.

Lincoln also visited a house of worship with Fillmore whilst in Buffalo.

I believe that upon viewing Niagara Falls, Lincoln said his thoughts were, “Where did all that water come from.”

Buffalo contributed the steel plates that opened and closed the gun ports of the Monitor.

My great great grandfather John Schiefer from Buffalo, NY was a soldier in the Civil war.

Buffalo contributed over 20,000 men to the Union war effort. Of that number, 4,704 of them were casualties. My question is , Where are they buried ? especially the 4704 causalities , I don’t think forest lawn has any casualties and only a small area for veterans, Concordia has a few some unmarked. In all I don’t think I could find 2,000

My grandfather’s grandfather fought with the 11th NY Calvary from Buffalo. He served on Lincoln’s bodyguard at the nation’s capitol and survived. His memoir describes the overwhelming enthusiasm for Lincoln during the Wide Awake parades in Buffalo!