“And So We Took Fort Sumter”

April 6, 1861. The plot thickens. The air is red-hot with rumors. The mystery is to find out where these utterly groundless tales originate.[i]

April 7, 1861. [Private section of the diary] News so warlike I quake. My husband speaks of joining the artillery. [missing lines removed by Mary] last night I find he is my all, and I would go mad without him.[ii]

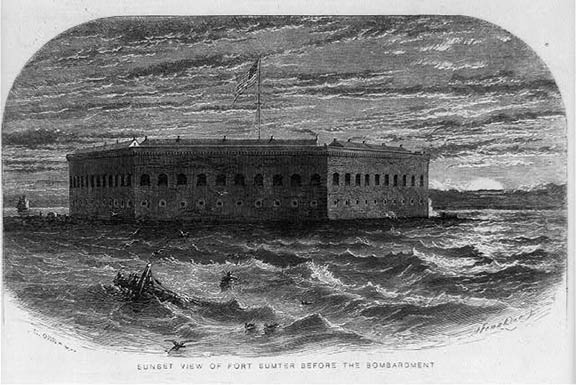

Mary Chesnut’s entries days before the first shots reveal the depth of her affection for her husband and help researchers understand the more personal fears that she suffered, along with emotion about the national division. As one of the extensive diarists of the Confederacy, she wrote a colorful, emotional, and fairly well-informed account of the firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. While some of her quotes about the opening shots are recognizable among the history community, her quotes pulled out to stand alone sometimes separates her words from the whole situation. Her husband, James Chesnut, Jr., was at the center of the unfolding bombardment and repeatedly crossed Charleston Harbor to keep the chain of communication open between Major Robert Anderson and the garrison of Fort Sumer to General Beauregard and the Confederate shore batteries.

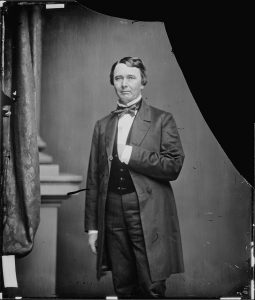

James Chesnut, a plantation owner and prominent South Carolina lawyer, was 46 years old in 1861 and had a record of political service. He had graduated from Princeton in 1835 and served in his homestate’s legislature from 1840-1858. He married Mary Boykin Miller in 1840, and they seemed to have a close relationship, though not always agreeing on all topics as she revealed in her private diary. For two years, 1858-1860, Chesnut represented South Carolina in the U.S. Senate, arguing for moderation in the fiery topics of the era. However, he resigned from the Senate in November 1860, the first senator to depart after Lincoln’s election was confirmed. James Chesnut voted in the South Carolina secession convention and followed the state government to Charleston.

The Chesnuts had been planning to leave the coast city to return to their plantation, but as Mary recorded sometime between April 7th and 11th: “Things are happening so fast. My husband has been made an aide-de-camp of General Beauregard. Three hours ago we were quietly packing to go home…. Now he tells me the attack upon Fort Sumter may begin tonight.”[iii]

As aide-de-camp, James Chesnut stepped into a role of communicator, wearing make-shift badges to represent his authority. His wife wrote about dinner on April 11th:

Today at dinner there was no allusion to things as they stand in Charleston Harbor. There was an undercurrent of intense excitement. There could not have been a more brilliant circle. In addition to our usual quartet (Judge Withers, Langdon, Cheves, and Tescot) our two governors dined with us, Means and Manning. These men all talked so delightfully. For once in my life I listened.

That over, business began. In earnest, Governor Means rummaged a sword and red sash from somewhere and brought it for Colonel Chesnut, who has gone to demand the surrender of Fort Sumter.

And now, patience—we must wait.

Why did that green goose Anderson go into Fort Sumter? Then everything began to go wrong. [iv]

While Mary spent the next historic hours in domestic safety, James Chesnut started his boat rides across the harbor to Fort Sumter where he met and communicated with Major Robert Anderson. With the arrival of the Federal resupply fleet, the issue at Fort Sumter was reaching a climax. The first message Chesnut carried read:

“I am ordered by the Government of the Confederate States to demand the evacuation of Fort Sumter. My aides, Colonel Chesnut and Captain Lee, are authorized to make such demand of you. All proper facilities will be afforded for the removal of yourself and command, together with the company arms and property, and all private property, to any post in the United States which you may select. The flag which you have upheld so long and with so much fortitude, under the most trying circumstances, may be saluted by you on taking it down. Colonel Chesnut and Captain Lee will, for a reasonable time, await your answer.”[v]

James Chesnut had been invested with authority from General Beauregard and the Confederate government. He carried back Anderson’s answers and then returned with another message from Beauregard, communicating:

“Major: In consequence of the verbal observation made by you to my aides, Messrs. Chesnut and Lee, in relation to the condition of your supplies, and that you would in a few days be starved out if our guns did not batter you to pieces, or words to that effect, and desiring no useless effusion of blood, I communicated both the verbal observation and your written answer to my communications to my Government.

If you will state the time at which you will evacuate Fort Sumter, and agree that in the mean time you will not use your guns against us unless ours shall be employed against Fort Sumter, we will abstain from opening fire upon you. Colonel Chesnut and Captain Lee are authorized by me to enter into such an agreement with you. You are, therefore, requested to communicate to them an open answer.”[vi]

Anderson sent back a decided answer in the very early hours of April 12:

“I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt by Colonel Chesnut of your second communication of the 11th instant, and to state in reply that, cordially uniting with you in the desire to avoid the useless effusion of blood, I will, if provided with the proper and necessary means of transportation, evacuate Fort Sumter by noon on the 15th instant, and that I will not in the mean time open my fires upon your forces unless compelled to do so by some hostile act against this fort or the flag of my Government by the forces under your command, or by some portion of them, or by the perpetration of some act showing a hostile intention on your part against this fort or the flag it bears, should I not receive prior to that time controlling instructions from my Government or additional supplies.”[vii]

At some point in the evening, James Chesnut saw his wife, but didn’t give her full details about the situation. She wrote in her journal in the early hours of April 12: “Anderson will not capitulate…. Our peace negotiator—or envoy—came in. That it, Mr. Chesnut returned—his interview with Colonel Anderson had been deeply interesting—but was not inclined to be communicative, wanted his dinner. Felt for Anderson. Had telegraphed to President Davis for instructions. What answer to give Anderson, &c.&c. He has gone back to Fort Sumter with additional instructions.”[viii]

Yet another time, James Chesnut headed across the harbor in the darkness. Anderson and the Federal garrison would not surrender, and the Southerners delivered a written ultimatum to prevent the fort’s resupply:

April 12, 3:20am

Sir: By authority of Brigadier-General Beauregard, commanding the Provisional Forces of the Confederate States, we have the honor to notify you that he will open the fire of his batteries on Fort Sumter in one hour from this time. We have the honor to be, very respectfully, your obedient servants, James Chesnut, Jr. (Aide-de-Camp), Stephen D. Lee (Captain, C.S. Army, Aide-de-Camp)[ix]

With Anderson’s refusal confirmed, James Chesnut was returning to shore for a last time. There he entered a battery and gave the orders. Back in her bedroom, Mary wrote in her diary. Somehow her husband or someone else had brought word of the message delivered to Anderson. She knew and feared what was coming.

I do not pretend to sleep. How can I? If Anderson does not accept terms—at four—the orders are—he shall be fired upon.

I count four—St. Michael chimes. I begin to hope. At half-past four, the heavy booming of a cannon.

I sprang out of bed. And on my knees—prostrate—I prayed as I never prayed before.

There was a sound of stir all over the house—pattering of feet in the corridor—all seemed hurrying in one way. I put on my double gown and a shawl and went, too. It was to the housetop.

The shells were bursting. In the dark I heard a man say “waste of ammunition.”

I knew my husband was rowing about in a boat somewhere in that dark bay. And that the shells were roofing it over—bursting toward the fort. If Anderson was obstinate—he was to order the forts on our side to open fire. Certainly fire had begun. The regular roar of the cannon—there it was. And who could tell what each volley accomplished of death and destruction….

Do you know, after all that noise and our tears and prayers, nobody has been hurt. Sound and fury, signifying nothing. A delusion and a snare.[x]

Over the next days, Mary recovered from her fears that Fort Sumter would blast the civilians in the city and began to somewhat enjoy the fact that her residence became a “news center,” particularly noting that the fort had caught fire. She collected rumors, tracked them, compared them with more reliable information from her friends in the military endeavors. She also tried to make sure she knew about her husband’s safety, finally noting at one point: “Somebody came in just now and reported Colonel Chesnut asleep on the sofa in General Beauregard’s room. After two such nights he must be so tired as to be able to sleep anywhere.”[xi]

On April 15, 1861, the end was confirmed, and Mary recorded the details about her husband’s role in her diary:

I did not know that one could live such days of excitement.

They called, “Come out—there is a crowd coming.”

A mob indeed, but it was headed by Colonels Chesnut and Manning.

The crowd was shouting and showing these two as messengers of good news. They were escorted to Beauregard’s headquarters. Fort Sumter had surrendered….

When we had calmed down, Colonel Chesnut, who had taken it all quietly enough—if anything, more unruffled than usual in his serenity—told us how the surrender came about.

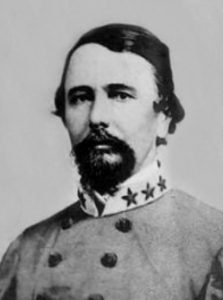

Wigfall was with them on Morris Island when he saw the fire in the fort, jumped in a little boat and, with his handkerchief as a white flag, rowed over to Fort Sumter. Wigfall went in through a porthole.

When Colonel Chesnut arrived shortly after and was received by the regular entrance, Colonel Anderson told him he had need to pick his way warily, for it was all mined.

As far as I can make out, the fort surrendered to Wigfall.

But it is all continuous. Our flag is flying there. Fire engines have been sent to put out the fire….[xii]

Some days or weeks later, Mary Chesnut reflected on the battle for Fort Sumter, placing her experience and her husband’s role in the same entry and concluding with an idea about the changing world they were creating.

And so we took Fort Sumter…. We—Mrs. Frank Hampton &c. in the passageway of the Mills House between the reception room and the drawing room. There we held the sofa against all comers. And indeed, all the agreeable people South seemed to have flocked to Charleston at the first gun. That was after we found out that bombarding did not kill anybody. Before that we wept and prayed—and took our tea in groups, in our rooms, away from the haunts of men.

Captain Ingraham and his kind took it (Fort Sumter) from the battery with field glasses and figures made with three sticks in the sand to show what ought to be done.

Wigfall, Chesnut, Miles, Manning, &c. took it, rowing about in the harbor in small boats, from fort to fort, under the enemies’ guns, bombs bursting in air, &c. &c.

And then the boys and men who worked those guns so faithfully at the forts. They took it, too—their way….

I have been sitting idly today, looking out upon this beautiful lawn, wondering if this can be the same world I was in a few days ago.[xiii]

The plot had thickened as the writer had predicted days earlier. James and Mary Chesnut were two players on the historic scene in Charleston in April 1861. Whether it was communications by crossing the dark harbor or recording the scenes witnessed, this couple was part of creating and recording a conflict that would ensure their world and the larger nation would never be the same again. A turning point for U.S. History had been launched…and the results are still emerging.

Sources:

[i] Mary Boykin Chesnut. Edited by C. Van Woodward. Mary Chesnut’s Civil War. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981). 41

[ii] Ibid., 43

[iii] Ibid., 44 (Not clear what day)

[iv] Ibid., 45

[v] Official Records, Volume 1, page 13

[vi] Ibid., 13-14

[vii] Ibid., 14

[viii] Mary Boykin Chesnut. Edited by C. Van Woodward. Mary Chesnut’s Civil War. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981). 46

[ix] Official Records, Volume 1, page 14

[x] Mary Boykin Chesnut. Edited by C. Van Woodward. Mary Chesnut’s Civil War. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981). 47

[xi] Ibid., 47

[xii] Ibid., 49

[xiii] Ibid., 51

Sarah, this is a lovely article