On the Eve of War: New Orleans, Louisiana

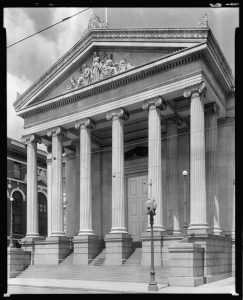

New Orleans is often called America’s most unique city. If not as true today, it certainly was in 1861. One major reason is no other major city in the country was acquired by America with a non-Anglo Catholic culture fully in place. The cultural mixture of French, Spanish, and West African, commonly thought of as Creole, made the city different from the likes of Boston and Charleston.

New Orleans is often called America’s most unique city. If not as true today, it certainly was in 1861. One major reason is no other major city in the country was acquired by America with a non-Anglo Catholic culture fully in place. The cultural mixture of French, Spanish, and West African, commonly thought of as Creole, made the city different from the likes of Boston and Charleston.

New Orleans’ development was different too. As a relatively isolated city, it remained a backwater of the French Empire, one that the British did not even bother to attack in the Seven Years’ War. Given away to a hesitant Spain, the colony rebelled in 1768. The Spanish therefore kept a sizable garrison considering how unprofitable the region was. They used that garrison to conquer Florida during the American Revolution. The advent of steamboats, America’s western expansion, and the rise of the sugar plantation converted Louisiana into an economic powerhouse in the early 1800s.

Only New York City rivaled New Orleans as a port and commercial center in 1861. However, it was a commercial center on the decline. The railroad was replacing the steamboat. If either cotton or sugar fell in value New Orleans had little to fall back upon. The city failed to develop industries, the wharves clogged with exports and drydocks for repairing rather than building ships. Still, few cities in the South could rival its productive capacity, and none could in size. New Orleans had a population of 170,000 by 1861. Not even the periodic ravages of yellow fever could dampen the growth of its populace. While immigrants from all over the world could be found, including Chinese dockworkers and Croatian oystermen, most were Irish and German. They were drawn by the economic opportunities and the city’s relative acceptance of Catholics.

Since the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the city was divided between Creoles and Anglo-Americans. Creoles were those whose ancestors came when Louisiana was a colony and they maintained those colonial traditions. Nearly all of them were of French, Spanish, and/or African heritage, since precious few people from anywhere else had settled in New Orleans before 1803. They were Catholic, but of a more liberal bent, and Spanish attempts to introduce a more robust and doctrinaire faith were dead on arrival. The first Anglo-Americans to come were a rough set, the famed flatboat men who first arrived in the 1780s, but were a transient population. As the city grew in economic importance, the next wave came from all over America. These people were here to make money and were Protestants. They clashed with the Creoles, who until 1850 held the political upper hand. So fraught were the relations that the Americans ensured the streets in their part of town had few French names. On the Creole side of Canal Street there was Bourbon, Dauphine, and the Elysian Fields. On the American side, there was Camp, Magazine, Washington, Jackson, Jefferson, and of course numbered streets, that dull passion American city planners.

The Creole and American split could be overstated. For one, the American side had some French street names, most famously Napoleon and a few routes named for his victories. The younger Anglos and Creoles were starting to marry and join militia companies, such as the famed Washington Artillery. Younger Creoles were starting to use French less while the Anglos became obsessed with the Catholic Mardi Gras tradition. Indeed, the Anglos introduced the float parade in the 1850s and generally saved the holiday from being banned, since Mardi Gras was a day when murders spiked, causing some to demand its cancellation. The split was of course still there, and many regiments that formed during the Civil War kept their separate identities, but the trend was for integration, at least for those Creoles who could pass for white.

When New Orleans was founded in 1718 every colony in the Western Hemisphere had slavery. Louisiana would be no different, in that regard, but quite different from the North American colonies owned by Britain and the Netherlands. These nations saw slaves almost exclusively as property. Spain and France saw them as Catholics, and as such slaves had some rights. The Spanish in particular gave slaves Sunday off, allowed them to gathered in certain designated parks (the most famous being Congo Square), and allowed them to buy their freedom. These free people of color varied in class and status. Many were day laborers, others craftsmen, and in a few rare cases even plantation owners. They served in the local military since the brutal 1725 Natchez War, and were praised highly by Andrew Jackson when he led the defense of New Orleans. In 1810 they made up roughly 40% of the population. By 1861 they were around 9%. The Anglos restricted the avenues to freedom, and as Anglos, Irish, and Germans poured in, their share of the population decreased accordingly.

The slaves of New Orleans were steadily dropping in numbers through the 1850s. The demand for plantation hands meant many were sold off and substituted for the Irish, who were cheap labor that could be fired at will. Laws governing slaves had become stricter, and a master could not even free their slave willingly. The Irish were seen as less of a burden by the wealthy, and they were fast replacing the slaves as the housekeepers of New Orleans. The Irish also worked the docks and dug canals, the later being deadly work in the marshes of the region.

New Orleans at this time was all about commerce. The fire department was among the best in America, the police department among the worst. The logic was simple. Fires destroyed commercial property, particularly cotton. Most victims of crime were poor immigrants. The same also explains why many were unfazed by yellow fever. It was called “stranger’s disease” because it killed immigrants and recent arrivals, but almost always spared the native born. Regardless, the prevalence of yellow fever, tuberculosis, and the odd cholera outbreak meant New Orleans had double the death rate of the average American city. Making it worse was crime. The city became known as the “Port of Lost Men” because many were murdered and dumped in the river. People such as Mary Jane “Bricktop” Jackson killed many and somehow always escaped justice. Gallatin Street near the river had a murder rate of roughly one person a day by some estimates. So why did anyone go there? Because it was filled with bars, brothels, and gambling halls. In the 1800s New Orleans was America’s sin city, where most versions of Poker were popularized. The professional gamblers of the era were folk heroes. One, the freedmen P.B.S. Pinchback, used his winnings to launch a post war political career, becoming America’s first black governor, marred though by a reputation for extreme corruption.

As with any sprawling and diverse city, the political battles were fraught and intense. The Creoles were Democrats, because they liked states’ rights, slavery, and immigration, the later of which allowed them to maintain some political power. Most Irish allied with the Creoles, and there was still a steady clip of French immigrants. The Anglos were Whigs, and when that party died they became Nativists or “Know Nothings.” Both parties used the gangs of the city to enforce their will, although the Nativists were more ruthless in this regard. Violent clashes were common, and outside of Mardi Gras, election day was the most bloodiest in the city. The Nativists though triumphed and from 1856-1862 they ran New Orleans.

Secession and war divided New Orleans. The white Creoles were nearly all for it. Many Anglos were opposed, particularly among the wealthy who saw the war as disastrous for commerce. The Irish had few loyalties to America and they brought a working class politics to New Orleans, which included an understanding that if slavery ended their wages would decrease. Two groups in a tough spot were the Germans and free people of color. The Germans were liberals, and while the more radical refugees of 1848 settled north, the Germans of New Orleans were lukewarm about slavery and secession. The free people of color were divided along class lines. The wealthier Creoles gave guarded support to secession. They had white relatives who were for the Confederacy and were themselves often mostly white in complexion. The famed Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau was herself ¼ African and a slave owner who, contrary to mythology, owned and never freed her eight slaves. One of them was even recaptured twice. While these Creoles were hardly fire-eaters, they understood that their precarious position relied on whatever influence and good will the white Creoles had, and if they were all in on disunion, then it made sense. Yet, the free people of color who were not Creole and poorer did not support secession, but had to be quiet about it. As for the slaves almost to a man they of course wanted the Confederacy to lose. Yet, while their status was the great turning wheel of the sectional conflict, they had no direct influence on the political debate over secession.

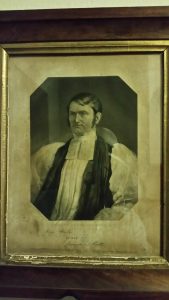

Before the election of 1860, the city seemed to carry on and most thought secession and war unlikely. Then Abraham Lincoln was elected. Editorials, cautious even in the lead up to the 1860 election, became fiery. In the lead up to secession there were parades, speeches, and bonfires. The Reverend Benjamin Palmer and Bishop Leonidas Polk used the pulpit to preach secession, hatred of Yankees, the positive good of slavery, and the right of free men to decide their relations to the government. In the midst of this chaos, P.G.T. Beauregard naively believed cooler heads would prevail, so much so he fought for and secured his place as superintendent of West Point. He was wrong, and would only be at West Point for three days, the shortest tenure to date. Before the year was out, he was the Confederacy’s premiere military hero, a status he held until Shiloh.

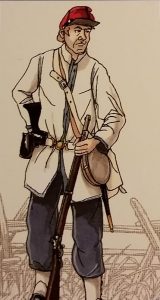

New Orleans went for war, perhaps not with the fervor of other cities and towns, but enough to furnish men and weapons. Most Louisiana regiments would sport at least a company from New Orleans, and usually much more. The unemployed dockworkers, now legion with the blockade, joined regiments and earned fearsome reputations on the fields of Bull Run, Shiloh, and many more. The Washington Artillery provided five elite batteries, and few major battles of the conflict did not see at least one of those batteries engaged. Yet, for all the excitement, New Orleans would lose its role as a top commercial center in 1861. The long decline began before 1861, but was sped up, and today we are a tourist center, where hardly a soul speaks French, Bourbon Street is the Disneyland version of Gallatin Street, and if the politics is less violent it is likely even more corrupt. No place has a pure golden age. Almost no one would want to return to the age when slavery and yellow fever were king, and crime was at levels that dwarf today. Yet, there was in 1861 a prominence and uniqueness. The city has chased after the former and commercialized the later, and with each generation it slowly looks more and more like anywhere else in America. Yet, before that last disgrace can occur, the waves will likely claim New Orleans, a fitting end for a city that has always existed on the brink of precarity.

Great write up of your city. I’ve spent a lot of time there, have family from there, but have never lived there. Like a lot of LSU students we move to either Houston, Dallas, or Atlanta these days… or some other place out of state.

Architecturally it is a unique place in America and it’s very compact thanks to the river, lake, and swamp. Most places in the U.S. allow for sprawl, whereas NOLA can only go so far before it must end. It’s not Manhattan, but it has its space confined by water.

Thanks to Sean Michael Chick for presenting a factual, complete as possible summary of pre-Civil War New Orleans. I’ll admit to feeling uncomfortable while reading about some of the idiosyncrasies of the historic Crescent City, but they are historic traits shared by many Gulf Coast communities and former Spanish Florida towns; and their histories cannot be understood without discussing them, warts and all. [One potential pathway to continued New Orleans prosperity not mentioned, but seriously promoted during the antebellum: the Tehuantepec Canal.]

Excellent reminder of what New Orleans was during the Civil War and afterward.