On The Eve Of War: An Englishman in Washington

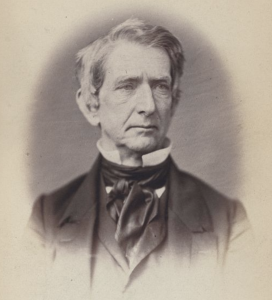

William Howard Russell, an influential reporter for The Times of London, toured America north and south in 1861-62 leaving a picturesque portrait of places, people, and issues. He is considered one of the first modern war correspondents for dramatic coverage of the Crimean War including the Siege of Sevastopol and the Charge of the Light Brigade.

Russell was in Washington DC on the eve of war meeting with and writing in elaborate Victorian prose about leading personalities on both sides but with not much sympathy for either. He brought both the clarity and the prejudices of an outsider’s perspective along with penetrating wit.

On April 4, 1861, Russell interviewed Secretary of State William Seward at the State Department: “He set forth at great length the helpless condition in which the President and the Cabinet found themselves….” The last cabinet tampered with treason, the secretary complained. “A miserable imbecility had encouraged the leaders of the South to mature their plans, and had furnished them with the means of carrying out their design.”

Officials of the previous administration dispatched the navy to distant stations, removed stores of arms, ordnance, and munitions to Southern States, and stole public funds for traitorous purposes. “In every port, in every department of the State, at home and abroad, on sea and by land, men were placed who were engaged in this deep conspiracy…. naval and military officers resigned en masse, that they might accept service in the rebel forces.”

President Lincoln’s duty was clear, Seward explained to Russell: “He had to guard what he had, and to regain, if possible, what he had lost. He would not consent to any dismemberment of the Union nor to the abandonment of one iota of Federal property — nor could he do so if he desired.”

However, the secretary was confident that “all this excitement would come right in a very short time — it was a brief madness, which would pass away when the people had opportunity for reflection.”

In the meantime, foreign powers should not imagine the Federal Government was too weak to defend its rights. “In other words, again, Mr. Seward fears that…Great Britain may recognize the Government established at Montgomery, and [he] is ready, if needs be, to threaten Great Britain with war as the consequence of such recognition.”

Seward assumed the existence of strong Union sentiments in many of the seceded States. If Southern people truly desired secession, he would let them go; it would not become the American spirit to use armed force against the will of a majority. “But he cannot believe in anything so monstrous, for to him the Federal Government and Constitution, as interpreted by his party, are divine, heaven-born.

“He is fond of repeating that the Federal Government never yet sacrificed any man’s life on account of his political opinions; but if this struggle goes on, it will sacrifice thousands — tens of thousands, to the idea of a Federal Union. ‘Any attempt against us [by a foreign power],’ he said, ‘would revolt the good men of the South, and arm all men in the North to defend their Government.’”

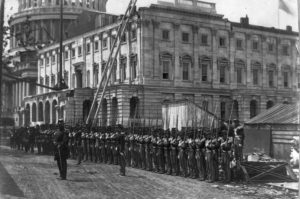

Just that day, Russell had witnessed an assemblage of men “doing a goose-step [and marching] forth dressed in blue tunics and gray trousers, shakoes and cross-belts, armed with musket and bayonet, cheering and hurrahing in the square before the War Department, who were, I am told, the District of Columbia volunteers and militia.”

They had been parading, marching, and trumpeting about “with a poor imitation of French pas and elan, but they did not, to the eye of a soldier, give any appearance of military efficiency, or to the eye of the anxious statesman any indication of the animus pugnandi [intention of fighting]. Starved, washed-out creatures most of them, interpolated with Irish and flat-footed, stumpy Germans.” (Russell was Irish himself.)

It was “matter for wonderment” for this reporter that a government in such imminent danger with its capital almost at the mercy of the enemy should employ bellicose language toward the most powerful nations of Europe. “Was it consciousness of the strength of a great people, who would be united by the first apprehension of foreign interference, or was it the peculiar emptiness of a bombast which is called bunkum? In all sincerity I think Mr. Seward meant it as it was written.”

That evening, Russell dined with Senator Stephen Douglas and a large party including Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, Interior Secretary Caleb B. Smith, and several senators and congressmen. Mr. John Forsyth, editor of the Mobile Register, also attended. He was a member of the Confederate States peace commission sent in March by President-elect Jefferson Davis to negotiate friendly relations with the United States. But President Lincoln and Secretary Seward refused to receive them. They were still hanging around Washington.

“Few men speak better than Senator Douglas,” Russell recorded. “His words are well chosen, the flow of his ideas even and constant, his intellect vigorous, and thoughts well cut, precise, and vigorous — he seems a man of great ambition….”

The senator expounded on a scheme to distract the people North and South from their troubles by uniting all North America—including Canada—in a free-trade zone resembling the “Zollverein,” a customs union among independent German states established under Prussian leadership in 1834 and the first of its kind.

“Mrs. Douglas did the honors of her house with grace and charming good-nature. I observe a great tendency to abstract speculation and theorizing among Americans, and their after-dinner conversation is apt to become didactic and sententious.” Had Mr. Douglas become president, opined the journalist with a bit of sarcasm, “his good-will towards Great Britain might have been invaluable, and surely it had been cheaply purchased by a little civility and attention to a distinguished citizen and statesman of the Republic.”

The next day, April 5, Russell met with the Southern peace commissioners and a small party at Gautier’s, a French restaurateur on Pennsylvania Avenue. In addition to Mr. Forsyth, the commissioners included former Louisiana Governor Andre B. Roman and former Georgia Congressman Martin J. Crawford. Also at Gautier’s were Col. Pickett and Mr. Banks, both notorious secessionists, and Mr. Phillips, who soon afterward would go South after his wife was arrested for “anti-federal tendencies.”

Russell declined to name other dinner guests for fear they would be exposed to “those marks of attention which [the government has] not yet ceased to pay to their political enemies.” He concluded that Americans had “forfeited all claim to the lofty position they once occupied as a Government existing by moral force, and by the consent of the governed,” a government now resorting to Bastilles, arbitrary arrests, and doubtfully legal if not unconstitutional suspension of habeas corpus.

“The gentlemen present were, I need not say, all of one way of thinking…. Mr. Forsyth is fanatical in his opposition to any suggestions of compromise or reconstruction; but, indeed, upon that point, there is little difference of opinion amongst any of the real adherents of the South.” They spoke of Mr. Lincoln with contempt but regarded Secretary Seward as the ablest and most unscrupulous of their enemies.

The acts of the previous administration, which Russell considered of doubtful morality, were justified to him in the name of States’ Rights. “If the States had a right to go out, they were quite right in obtaining their quota of the national property which would not have been given to them by the Lincolnites. Therefore, their friends were not to be censured because they had sent arms and money to the South.”

The entire Northern race had, contended his dinner companions, been degraded by the pursuit of gain through commerce, manufacture, and the mechanical arts; Yankees would never attempt to strike a blow in fair fight. Whether it was the pernicious influence of slavery or the threat to their institutions, thought Russell, these men exhibited the deepest animosity and most vindictive hate. “Certain it is there is a degree of something like ferocity in the Southern mind towards New England which exceeds belief.”

The reporter was persuaded that similar feelings of contempt were extended towards Great Britain. “They believe that we, too, have had the canker of peace upon us. Evidence of this, according to Southern men, is the abolition of dueling. This practice, according to them, is highly wholesome and meritorious.” Russell admitted, given the apparent state of their society, dueling might be a useful check on such violent men as it had been in his own nation in the previous century.

One gentleman remarked that it would be disgraceful for any man to accept money in recompense for the dishonor of his wife or daughter. The man who dares tamper with the honor of a white woman knows what to expect: “We shoot him down like a dog, and no jury in the South will ever find any man guilty of murder for punishing such a scoundrel.”

In “an argument which can scarcely be alluded to,” recalled Russell, the Southerners admitted that such offenses might be handled less drastically in states that were mostly white. “Indeed, in this, as in some other matters of a similar character, slavery is their summum bonum of morality, physical excellence, and social purity.”

Russell was inclined to question whether virtue needing the murderous application of pistol and dagger to defend it was not open to some doubt, but found no sympathy with that view. “The gentlemen at table asserted that the white men in the Slave States are physically superior to the men of the Free States; and indulged in curious theories in morals and physics to which I was a stranger.”

“Disbelief of anything a Northern man — that is, a Republican — can say, is a fixed principle in their minds.” When the company protested the duplicity of Secretary Seward and the Federal Government in refusing to give assurances that Fort Sumter would not be relived by force, Russell noted that it could make little difference if they always lied anyway.

The notion that such men were cowards as well as liars was justified by instances in which Northerners insulted by Southern men failed to call them out. The brutal beating in the Senate chamber of Massachusetts Republican Senator Charles Sumner by South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks was cited as an example.

Russell explained his understanding that Mr. Summer had been attacked suddenly and unexpectedly, struck down before he could rise from his desk to defend himself. He was warmly refuted by assurances that Mr. Brooks, a slighter and shorter man than Mr. Sumner, administered a minor first blow and then justifiably inflicted heavier strokes only when irritated by the senator’s cowardly demeanor.

“In reference to some remark made about the cavaliers [of the English Civil War] and their connection with the South, I reminded the gentleman that, after all, the descendants of the Puritans were not to be despised in battle and that the best gentry in England were worsted at last by the train-bands of London, and the ‘rabbleclora’ [rabble?] of Cromwell’s Independents.”

Concluded Russell: “Altogether the evening, notwithstanding the occasional warmth of the controversy, was exceedingly instructive; one could understand from the vehemence and force of the speakers the full meaning of the phrase of ‘firing the Southern heart’….” He was almost certain that “the colored waiters who attended us at table looked as sour and discontented as could be and seemed to give their service with a sort of protest.”

And thus to this Irishman, the lines were clearly drawn in Washington.

Source: William Howard Russell, My Diary North and South (Boston, 1863), 60-66.

It is always left out of the story that Charles Sumner had specifically insulted Preston Brooks’ cousin, who was in some way compromised in speech and/or mental abilities. Sumner may have done this in the course of insulting Southerners in general; he was a brilliant man with a sharp tongue.. It is of course far more politically expedient to blame Brooks’ attack on Sumner’s anti-slavery rhetoric.

“Bull Run” Russell! Talk about sabotaging one’s one journalistic credibility…. He was one of the most famous (and successful) journalists of his day. His dispatches drew ire from both north and south, and so he had plenty of critics hoping to see him fall on his face–which he did with his botched reporting of First Manassas. Good cautionary tale there!

Thanks to Dwight Hughes for his concise introduction of William Howard Russell: the representative of the Press potentially wielding the power to swing British public opinion in favour of Lincoln or Davis.

The first transatlantic cable connecting America to Britain was completed in 1858; it provided near instant telegraphic communications, but only functioned for three weeks before going permanently silent. The next cable, laid by “Great Eastern” was attempted in 1865. Hence, the Civil War was conducted during a period totally reliant upon steamships for hauling the mail… and broadcasting the News. And the accepted wisdom of the day attributed “about a month” to the time a report would leave the pen of William Howard Russell; cross the Atlantic; be published in The London Times; re-cross the Atlantic; and a copy of that newspaper containing Russell’s report find its way back to Washington or Charleston. Therefore, Government officials North and South attempted full powers of persuasion “to get the English on their side,” and provided unfettered access to military camps and senior generals (believing the military intelligence divulged would be of little value after a month.)

But, both sides attempted to embed spies with the British War correspondent; and both sides were incensed when reports “from Russell” appeared in local papers mere days after access was granted to the information. “My Diary, North and South” reads like the travel journal it is, and provides unvarnished insights to significant Civil War figures and military preparedness, not available anywhere else: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000195397

Imagine if the original 1858 cable had not failed! That was as fast as email today, although likely with limited capacity.