“The Escapes…Are Very Numerous”

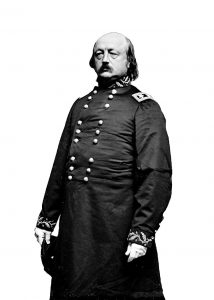

One hundred and sixty years ago, Benjamin Butler enjoyed his new rank as major general of volunteers, a result of occupying Baltimore and helping to secure the transportation and communication lines into Washington D.C. His new assignment at the end of May 1861 involved securing Fortress Monroe at the end of the Virginia Peninsula at the mouth of the James River. Shortly after his arrival and before dispatching troops to seize Newport News, Butler encountered a situation that would ultimate be part of a significant change in the Union’s war causes.

Enslaved men, women, and children sought escape and freedom within the narrow Union lines on the peninsula. Freeing enslaved was not a general war-aim for the North in the early part of 1861, but the steps of self-emancipation taken by African Americans in their escape to Fortress Monroe forced military men and politicians to begin asking important questions about freedom and the war effort.

The following dispatch published in the Official Records reveals General Butler’s dilemma. He had already determined not to send former enslaved men back to their angry overseers, and he fully recognized that slavery involved treating and valuing humans as property. The arrival of families prompted further contemplation of the situation, and Butler tried to divide his thoughts into military, political, and humanitarian categories. The self-emancipation movement would continue, eventually prompting Butler to create the term “Contraband of War” for the newly freed people.

The Civil War was barely a month begun and a major battle had yet to be fought by the end of May 1861. Already, the questions of freedom, enslavement, and emancipation were appearing in dispatches from the military front and landing on politicians’ desks. Months would pass before the Lincoln administration made any moves toward emancipation, but the seeds of freedom had been planted as families ran to a Federal fort and General Butler contemplated the situation:

May 27, 1861

…Since I wrote my last dispatch the question in regard to slave property is becoming one of very serious magnitude. The inhabitants of Virginia are using their negroes in the batteries, and are preparing to send their women and children South. The escapes from them are very numerous, and a squad has come in this morning to my pickets, bringing with them their women and children. Of course these cannot be dealt with upon the theory on which I designed to treat the services of able bodied men and women who might come within my lines, and of which I gave you a detailed account in my last dispatch.

I am in the utmost doubt what to do with this species of property. Up to this time I have had come within my lines men and women with their children—entire families—each family belonging to the same owner. I have therefore determined to employ, as I can do very profitably, the able-bodied persons in the party, issuing proper food for the support of all, and charging against their services the expense of care and sustenance of the non-laborers, keeping a strict and accurate account as well of the services as of the expenditures, having the worth of the services and the cost of the expenditures determined by a board of survey, hereafter to be detailed. I know of no other manner in which to dispose of this subject and the questions connected therewith. As a matter of property to the insurgents it will be of very great moment, the number I now have amounting, as I am informed, to what in good times would be of the value of $60,000. Twelve of these negroes, I am informed, have escaped from the erection of batteries on Sewell’s Point, which this morning fired upon my expedition as it passed by out of range. As a means of offense, therefore, in the enemy’s hands, these negroes, when able-bodied, are of the last importance. Without them the batteries could not have been erected, at least for many weeks.

As a military question, it would seem to be a measure of necessity to deprive their masters of their services. How can this be done? As a political question and a question of humanity, can I receive the services of the father and mother and not take the children? Of the humanitarian aspect I have no doubt. Of the political one I have no right to judge. I therefore submit all this to your better judgment; and as these questions have a political aspect, I have ventured—and I trust I am not wrong in so doing—to duplicate the parts of my dispatches relating to this subject, and forward them to the Secretary of War.

(Excerpt from the May 27, 1861 dispatch; paragraphs added for easier reading)

This is a really cool write up! Fascinating to see how the General categorized the issues in his head.

IIRC, Washington told him initially to send the enslaved persons back to their owners, but to his credit he resisted. Later, the federal government would take his stance on the matter.

Tom