Recruiting the Regiment: The 2nd Maine Volunteer Infantry

Eight days after the rebel bombardment of Fort Sumter, Daniel White, a resident of Bangor, Maine, wrote a letter to his governor. “I have the honor to inform you that at a meeting of the Ex-Tiger & Armory Associates,” White scribbled, “it was voted to tender their services to the government of the United States as a part of the troops sent from this state.”[1] The Ex-Tigers, as they called themselves, included members of the Bangor Fire Department who were suddenly caught up in the martial spirit that flooded the streets of their town. In due time, they would become Company G of the 2nd Maine Infantry. Though numerically the 2nd Maine, the regiment would be the first sent off to war from the Pine Tree State.

Eight days after the rebel bombardment of Fort Sumter, Daniel White, a resident of Bangor, Maine, wrote a letter to his governor. “I have the honor to inform you that at a meeting of the Ex-Tiger & Armory Associates,” White scribbled, “it was voted to tender their services to the government of the United States as a part of the troops sent from this state.”[1] The Ex-Tigers, as they called themselves, included members of the Bangor Fire Department who were suddenly caught up in the martial spirit that flooded the streets of their town. In due time, they would become Company G of the 2nd Maine Infantry. Though numerically the 2nd Maine, the regiment would be the first sent off to war from the Pine Tree State.

Even before the firefighters voted to offer their services, efforts were underway to create a regiment. Levi Emerson, formerly a police officer in Bangor, opened the first recruiting office on April 18, with an ad in the newspaper proclaiming, “A volunteer company is now forming for the purpose of offering their services to the Governor. Able bodied men who wish to serve their country, can report themselves at the Taylor store Office, over Finson’s Market, Mercantile Square, Bangor.”[2]

Bangor, a city of about 16,000 in 1861, offered so many soldiers and support in the creation of the 2nd Maine that it became known as the “Bangor Regiment.” Fully seven of the regiment’s ten companies all came from Bangor, with others coming from Brewer (just across the Penobscot River) and Castine. There were the aforementioned firefighters and cops, and then they were joined by mariners, fishermen, lumbermen, and every other job one could think of as they flooded in to join.[3]

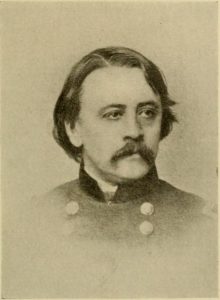

Some of the recruits had limited military experience already, being part of Maine’s antebellum militia. The militia is also where the regiment got its commander from. Born in Gorham, but raised in Old Town and Orono, Charles D. Jameson’s service in the Maine militia gave him a “commanding presence.” Though a Democrat, Jameson supported the war and ardently offered his services to Maine and the nation. Elected colonel of the regiment, Jameson’s commission was dated May 2, 1861.[4] Once filled in, the regimental staff also included among its members Surgeon Augustus Hamlin, nephew of the Vice President.

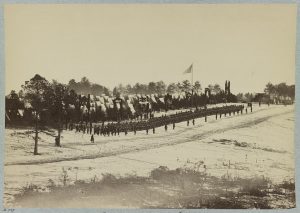

Throughout late April and early May, the companies came together in Bangor. As they did, Colonel Jameson threw them into drill. He wrote to the state’s adjutant general, “We are trying to improve in drill & camp duty, but I assure you it is uphill business.”[5] Governor Israel Washburn, pleased with the regiment’s progress, wrote to Secretary of War Simon Cameron, “The Second Regiment. . . will be ready to march Wednesday May 8th.”[6]

The governor’s date was optimistic, but only by six days. Colonel Jameson received orders that the regiment was to start its journey for Washington on May 14. The local newspaper, the Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, wrote, “It has been organized, clothed, equipped and prepared for movement with very great dispatch, considering all the circumstances.” The paper concluded with pride, “We doubt whether another regiment in Maine will or can be put in marching order in the same length of time.”[7]

On May 14, before the 2nd marched out, it received “by the ladies of Bangor. . . a beautiful set of colors, made of silk, surmounted by the emblematic eagle in gold, with heavy gold tassels.” After the few appropriate remarks by Colonel Jameson, the regiment began its march to the railroad depot. As the soldiers marched, they were “accompanied by an immense concourse of people from the whole city and vicinity, who had come out to see their friends depart for the defence of the country.” Even a steady rainfall wasn’t enough to dissuade the crowd to disperse, and the soldiers boarded the waiting trains.[8]

May 15 found the regiment in Portland, where it boarded more trains to Boston. From there, they made their way to New York City. It was in New York City that the regiment had the first of its problems that threatened to derail their triumphant entry into the war. In fact, it was the same problem that plagued its predecessor in number, the 1st Maine. Measles had swept through the 1st Maine, delaying its departure from Maine, and allowing the 2nd to take up the mantle of the first Pine Tree State soldiers to head for Virginia. While in New York, a surgeon reported measles in the camp of the 2nd, requiring them into quarantine until May 30. The Mainers were not displeased, though, finding the “balmy May air. . . enjoyable” and the hospitality of the locals saw to the wants and needs of the soldiers.[9]

The other problem wasn’t as obvious or noticeable right away, and that concerned the regiment’s enlistment papers. In the rush to join the service, many soldiers signed three-month papers, as did so many thousands of others in the spring of 1861. That quickness led one writer to summarize, “In the haste incident to enrolling troops and getting them to the front, many blunders were made, not only by the U.S. Government, but by the State authorities and men.”[10] Soon after signing their 3-month papers, the soldiers in the 2nd Maine received word that the state legislature had passed resolutions calling for two year enlistments, which many soldiers willingly agreed to, and signed the corresponding paperwork. But while in quarantine, the regiment was visited by Lt. Milton Cogswell, 8th U.S. Infantry, who was there to muster the 2nd into Federal service. It was Cogswell’s understanding that the 2nd Maine was to sign three-year papers, not two. Many soldiers protested, and others refused to sign the three-year contracts, though about 120 Maine soldiers did. Though it wasn’t an obvious problem in late May 1861, it would become one in May 1863—a story familiar to many modern readers as it climaxed with Joshua Chamberlain, the 20th Maine, and the battle of Gettysburg.[11]

With their quarantine finished and the enlistment fiasco settled (at least for the time being), the 2nd Maine continued its journey to Washington, D.C. They settled into camp outside of the city and waited for what came next. The soldiers arrived, like most Maine soldiers at the time, wearing uniforms that would soon lead to confusion: “grey frock coats, pants, and fatigue caps, with heavy overcoats of the same material.” They carried a mixture of muskets converted from old flintlocks and newer Springfield arsenal muskets. The women of Bangor had raised enough money to buy linen for 800 white havelocks which were sent to the regiment, though like most other soldiers, the Mainers found the havelocks more a nuisance than worth.[12]

A final gift awaited the 2nd Maine, and they received it just a day before the war’s first big battle. On July 20, outside of Centreville, the 2nd received yet another flag, this one paid for by Mainers living in San Francisco. The new banner had cost $1,200 dollars and had been made with the intention of being presented to whichever Maine regiment arrived in Washington first. With their third flag at the front of the regiment, the Mainers went into their first battle the next day, losing from killed, wounded, and captured 155 soldiers.[13]

It was their first battle, but it would not be their last. When the survivors returned to Maine in 1863, the same crowds that had sent them off to war welcomed them home. Bangor’s mayor “requested persons to close places of business this afternoon, during the reception of the Second Maine,” and “The Regiment was received in the usual form and escorted to Broadway, where an immense throng had assembled, filling the entire square.”[14]

______________________________________________________________

[1] Daniel White to Gov. Israel Washburn, April 20, 1861.

[2] R.H. Stanley and George O. Hall, Eastern Maine and the Rebellion (Bangor: R.H. Stanley & Company, 1887), 22.

[3] William E.S. Whitman and Charles H. True, Maine in the War for the Union: A History of The Part Borne by Maine Troops in the Suppression of the American Rebellion (Lewison: Nelson Dingley Jr. & Co., 1865), 37-38.

[4] Ephraim O. Jameson, The Jamesons in America, 1647-1900: Genealogical Records and Memoranda (Boston: The Rumford Press, 1901), 278-279; Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964), 250.

[5] Colonel Charles D. Jameson to State Adjutant General John L. Hodson, May 7, 1861.

[6] Governor Israel Washburn to Sec. of War Simon Cameron, April 29, 1861.

[7] Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, May 13, 1861.

[8] Whitman and True, 38.

[9] Stanley and Hall, 55.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Whitman and True, 38; See Thomas A. Desjardin Stand Firm Ye Boys from Maine: The 20th Maine and the Gettysburg Campaign (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

[12] Ron Field, Rally Round the Flag: Uniforms of the Union Volunteers of 1861, The New England States (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing, 2015), 115-117.

[13] Whitman and True, 40; The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. 51, pt. 1, 17.

[14] Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, May 26 and May 27, 1863 issues.

1 Response to Recruiting the Regiment: The 2nd Maine Volunteer Infantry