Antietam’s Lower Field Revisited Part IV: A.P. Hill’s Not-So-Devastating Counterattack

One of the most celebrated episodes of the entire war is the nick of time arrival of General A.P. Hill’s division to save the day for the Confederates at Antietam. In a made for Hollywood type of moment, the Confederate reinforcements arrive in exactly the right place at exactly the right time.

Closer examination reveals that General A.P. Hill’s late day counterattack was actually more limited and not as devastating as is generally believed, Hill’s entire division lost only 346 men and was engaged for about two hours. Only three of Hill’s brigades, those of Gregg, Branch, and Archer even entered the fight.

These units, like most in the Army of Northern Virginia, were also severely understrength. They had endured the combat of the Seven Days that summer, then the Second Manassas Campaign, and the rapid march into Maryland. After securing the captured garrison and supplies at Harpers Ferry, they made a rapid 12-mile march to Sharpsburg, foregoing the usual breaks that such a march entails.

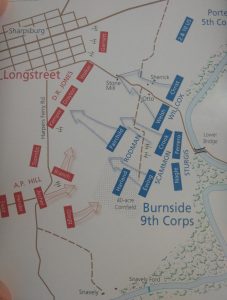

The three brigades of Hill’s division which entered the fight, Gregg’s, Branch’s, and Archer’s, had about 2,000 men combined, giving each brigade roughly 650 men, or each regiment about 170. The first to deploy and strike were Gregg’s South Carolinians, yet it was unevenly done. The brigade moved from the Harper’s Ferry Road downhill towards the unsuspecting troops of the 4th Rhode Island and 16th Connecticut in a cornfield. The 1st, 12th, 13th, and 14th South Carolina and Orr’s Rifles spread out as they entered the 40-acre Cornfield and engaged the 16th Connecticut and later the 4th Rhode Island. The Confederate attack was devastating but disjointed. The 1st and 12th regiments advanced too far and actually had to fall back into the cornfield, then advanced again to drive the Union troops back.

Coming in next was North Carolina brigade of General Lawrence O. Branch. Hill himself ordered the 28th forward to support a battery and sent the 7th and 37th moved forward straight towards the isolated 8th Connecticut, driving them back. The 18th North Carolina (later famous as the unit who likely shot Jackson at Chancellorsville) was sent off to the right and not engaged. Thus, only two regiments of the brigade, the 7th and 37th, were engaged.

Last into the fight was Archer’s Tennessee brigade, only 350 strong. Archer himself was ill, having arrived in an ambulance, but mounted his horse once on the scene. The Tennesseans pushed up to the front line and assisted in blunting the impact of newly arrived Ohio troops.

General Branch, a promising and well-respected officer, was consulting with Archer and Gregg as darkness fell. Branch raised his glass to have a better look and at that moment he was hit in the right cheek, and the bullet exited out the back of his head, killing him instantly. He fell by the side of the other two startled generals.

Following the repulse of the advanced units (8th and 16th Connecticut, 4th Rhode Island, 9th New York), the reserve units of the Kanawha Division moved up to shore up the line, the 11th, 12th, 23rd, 28th, 30th and 36th Ohio. By this time Hill’s three brigades were supported by a general advance by D.R. Jones’ division. His very understrength (about 2300 men) units of Toombs, Kemper, Drayton, and Garnett.

The Union troops all fell back to the high ground just west of the bridge. Here on high ground, behind a fence, and in a compact position, they could hold off any assault. Sunset at 6:15 ended the fighting.

One of the more famous parts of the battle was the confusion caused by some of A.P. Hill’s troops wearing captured Union uniforms from Harper’s Ferry. Has it been exaggerated? Which units had blue coats and how many troops may have actually wore them? This issue is worth exploring in more detail. Accounts from the 16th Connecticut and 4th Rhode Island mention the enemy in front of them (Gregg’s South Carolinians) were in blue, but were there others (Branch’s and Archer’s men)? Were whole regiments in blue or just part of them? Confederate accounts contain few details and it is hard to quantify from the evidence we have.

Hill’s division had arrived in time and at the right place. Yet it only brought about 2,000 men and only fought for about two hours. They lost only 346 men (63 killed and 283 wounded), most of them in Gregg’s brigade.

Postwar memoirs emerged in the 1880s and1890s that fit with Lost Cause narrative, in this case, outnumbered, hungry, tired Confederates turned back a Union tidal wave. An address of General B.T. Johnson in 1884 noted that at this point in the battle “The Confederates were used up.” Yet the Union had overwhelming numbers at their disposal in the form of three corps: “Franklin was fresh, Porter was fresh, Burnside was fresh.” “There was no help for Lee unless A.P. Hill got up in time . . .” Of course, the fact is that nearly half of the Ninth Corps had already fought and suffered fatigue and casualties. There were also many inexperienced troops who were seeing their first combat here. Also Porter’s corps was not within supporting distance and was dispersed.

Johnson continues, noting that “A.P. Hill, with 2,000 men, assisted by Toomb’s Brigade (which at that time didn’t number present 1,000), actually drove back and routed 14,000 fresh Federal soldiers under Burnside, and that, too immediately after a forced march and fording the Potomac!” Again, this telling exaggerates the numbers.

This is all not to say that A.P. Hill’s attack was insignificant, for it threw the Ninth Corps back, and stabilized the Confederate line. Yet it is worthwhile to take the measure of its scale and dig into the details of the attack. There was a good deal of maneuver and back-and-forth by both sides before darkness fell.

The author thanks Kevin Pawlak for his advice and input.

The troop counts for Hill’s Division provide new and telling information

A vivid account and worth expanding!

As it is with all events in history there are many variables that enter the story. Your article scratches the surface of the reality of the outcome.

Hill left two brigades behind at Harpers Ferry and at Pack Horse Ford to guard the crossing.

Terrain between the bridge and Sharpsburg is intense, and the time of day all fell together to end it for the day. I’ve always thought that Lee got away with one here at Sharpsburg.

About 12,000 federals were paroled by Hill’s command at Harper’s Ferry. Those Union troops marched away without guard (later to be interned in a Union-operated parole camp). If those U.S. soldiers had refused parole, forcing the detachment of a sizable CSA force to guard and escort them South, the result at Sharpsburg might have been very different. This mass parole, and a similar result in Richmond, Kentucky the same month, helped cause a change in federal policy, restricting the ability of Union soldiers to accept paroles.

Sorry Bert (and Kevin). but a supposedly historical article looses any credibility once a so called “historian” resorts to calling known facts “lost cause narrative”. General Hill did in fact arrive at the right place at the right time. After their march (where many fell out from exhaustion) they were certainly as or more fatigued as any of the Union forces they faced in Battle. His 2,000 men did turn the tide despite the digging for excuses as to why. Including some rather foggy “blue jacket” theory.