Echoes of Reconstruction: An Immigrant Defender of Black Freedom

ECW is pleased to welcome back Patrick Young, author of The Reconstruction Era blog

June is Immigrant Heritage Month, and no American military conflict was more impacted by immigrants than the American Civil War. Roughly a quarter of the United States forces were immigrants, giving the Union a decided manpower advantage over the Confederacy. This month I want to talk about an immigrant who came to America before the Civil War, served in the United States Army, and continued to serve his adopted country after the war.

When Felix Brannigan wrote to his sister in the summer of 1862 he probably did not think that anyone outside of his immediate family circle would see his soldier’s letter home. Brannigan was part of the Union Army of the Potomac that had failed days earlier to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. The Irish immigrant had heard that a series of Union defeats was pushing President Lincoln towards the emancipation of the slaves. Brannigan denounced this possibility in the most racist language possible in what he assumed was a private note to his loved one. He could not know that it would be reprinted more than a dozen times in history books.

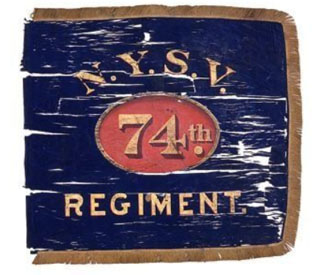

Felix Brannigan was an early volunteer in the Union army. He joined the army in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on April 22, 1861. Although he signed-up for the army in Pennsylvania, his unit was incorporated into the 74th New York Volunteer Infantry, part of New York’s Excelsior Brigade.

Brannigan was white-hot with hatred for the Southern aristocrats who had led the secession movement as well as for native-born New Yorkers who failed to enlist in the army to save their country. Brannigan wrote that “It makes even a foreigners blood boil to look at the apathy” of men unwilling to risk their lives to preserve “a country which is looked upon by the oppressed of all nations as a haven of liberty.” He insisted that the Union would win the war if the men of the North enlisted en masse.

While Brannigan wanted white Northerners to join him in the army, he had no desire to have black men serve with him. “We don’t want to fight side and side by the n*gger,” he wrote. “We think we are too superior a race for that.” He wrote to his sister that he would “let the n*ggers be sent here to use the pick and shovel” to perform the hard manual labor “in the broiling sun” of building fortifications. This, he wrote, would allow white men now engaged in such work to pick up the “soldiers tool-the gun and bayonett.”

Racism was not confined to lower ranking officers and men. William T. Sherman, who may have freed as many slaves as any general in the Union army, wrote in 1864 that “I like n*ggers well enough as n*ggers, but when fools & idiots try & make n*ggers better than ourselves I have an opinion.” While he said that the South was being punished for its “injustice” towards blacks, he warned that there “is no reason why we should go to the other extreme.” [Sources]

While Felix expressed the most extreme opposition to serving with Blacks, the announcement from Washington that African Americans would be enlisted did not lead him to desert. In fact, he was awarded the Medal of Honor for his bravery at Chancellorsville. Then he made a move that seemed like a complete reversal of opinion. Brannigan decided to seek a position as an officer leading African-American troops. [Sources]

Immigrants appear to have been more likely to request a commission as an officer in the newly organized regiments of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). The army had not allowed black men to enlist in large numbers until 1863. When they were finally admitted to service they were placed in segregated regiments in which all the enlisted men were Black and all of the officers were white. With 180,000 Blacks entering the army in just two years, new officers were needed immediately.

Some immigrants joined the black units because they supported the emancipation of slaves and saw the new regiments as legions of liberation. This was a particularly common reason among Germans, whose liberalism impelled them to end slavery. German immigrant Francis Lieber expressed the emotional reaction of German liberals to black enlistments. When he saw a black regiment presented with its flag in New York City a year after the July 1863 Draft Riots, he wrote to his friend Senator Charles Sumner that: “There were drawn up in line over a thousand armed negroes, where but yesterday they were literally hunted down like rats. It was one of the greatest days of our history.”

Other immigrants believed that, whatever the merits of Emancipation, now that it was an accomplished fact, black troops would add needed firepower to a Union army decimated by combat losses. Still other immigrants sought commissions in the Colored Troops because they faced discrimination in advancement in non-ethnic white regiments. Some native-born men simply did not want to be under the command of a “foreigner,” making it difficult for immigrants to get ahead. Joining a USCT regiment at a time when thousands of new officers were needed to command black soldiers was a road to promotion.

Whatever the reason Felix Brannigan had, by Christmas of 1864 he was a Second Lieutenant in the 32nd United States Colored Troops. This regiment was stationed along the Carolina coast when he joined it. Two months later, it occupied Charleston, South Carolina, the city where the Civil War had begun with the attack on Fort Sumter in 1861.

In the last month of the war, April 1865, Brannigan joined the 103rd USCT as Adjutant. The regiment had been organized only weeks before Brannigan was assigned to it. The 103rd was made up almost entirely of former slaves and free blacks from South Carolina. Its mission, in the first few months after the war, was to liberate blacks still held as slaves two and a half years after Emancipation and guard against guerrilla activity by whites hoping to reestablish control over the black population. The immigrant officer left the army in August 1865.

After the war, Brannigan studied law and became an attorney. In 1868 he finally became a United States Citizen. In the 1870s, he returned to the South to help uphold the civil rights of freed slaves who had only been constitutionally recognized as United States Citizens since 1868. Brannigan served in the United States Attorney’s office in Mississippi at a time when the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups were assassinating anyone who defended the rights of African Americans.

The outgoing U.S. Attorney for Jackson, Mississippi, E. Phillip Jacobson wrote to President Ulysses S. Grant on April 16, 1873 that he should consider Felix Brannigan as his replacement. Brannigan, he wrote, was “most entitled to your consideration.” The Irish lawyer was serving as Jacobson’s assistant and was “fully familiar” with the duties of the United States Attorney. He had been Assistant U.S. Attorney for a year and a half, and Jacobson wrote “I am able, from personal observation, to testify to his gallantry.” According to Jacobson, “Mr. Brannigan has enjoyed the confidence of the Government ever since in various official situations and is well known to the Solicitor of the Treasury…” The young soldier whose gallantry had won him the Medal of Honor on the battlefield was now hailed for the same trait as a lawyer administering justice in Reconstruction Mississippi. [Sources]

The language of the last paragraphs in this article severely mischaracterize the nature of events in the South during Reconstruction, and leaves out very relevant facts: 1) Southerners were not “assassinating anyone” who defended African American voting rights, evident in the fact that quite a few African Americans and Northerners in the South survived the period entirely unscathed, and 2) there is no mention whatsoever of the fact that Southerners were disenfranchised across the board during Reconstruction, which of course does not excuse any “assassinations” but does add significant depth to the discussion. In addition, African-American voting rights were being supported by the North entirely for the purpose of developing a Republican voting rights, a fact so widely recognized that to leave it out of this post is truly disingenuous. Mr. Brannigan likely did not lose his innate racism but simply followed whatever course of action served his chosen sides purposes at the time. The USCT served admirably and honorably, but they were segregated, commanded by white officers, initially underpaid and underequipped, and used on more than one notable occasion as cannon fodder. Posing Mr. Brannigan as an example of racism redeemed does not work. I haven’t even mentioned that much of the activity of ‘local Southern militia” was aimed at keeping law and order in an era of extreme dislocation and economic turmoil, for the simple reason that I would then be subjected to a stream of vitriol focused on the theme “racist”….and there were excesses; Nathan Bedford Forrest asked the Governor of Tenn. to disband the KKK as their activities became more extreme. And it needs to be mentioned that even had Mr. Brannigan reformed his attitude, most of the immigrant population who served the Union had the same attitude and kept it through ensuing generations.

Southerners were not disenfranchised “across the board during Reconstruction.” This is nonsense. In most elections more people voted during Reconstruction than had voted during the years before the Civil War.

Actually, all who had served in the Confederacy were indeed disenfranchised. And that meant the vast majority of Southern whites. Interesting to note the few whites allowed to vote were those who remained loyal to the Union. It was these people who voted against the 14th amendment given the pro-Confederate vote was not allowed. It was Union loyal voters who then were disenfranchised for having voted against the 14th.

Patrick Young Disingenuous reply – white Southerners were disenfranchised variously until their individual States were readmitted to the Union. This is easily available information.

This article begs for much needed balance. Here are some quotes from the article along with my comments:

“The Irish immigrant had heard that a series of Union defeats was pushing President Lincoln towards the emancipation of the slaves.”

In reality, there is strong evidence that suggests Lincoln’s EP was a reaction to a CSA offer to end slavery in hopes of gaining foreign support in its war for independence. Lincoln’s EP was prompted as an attempt to head off a CS emancipation which he was informed about in a meeting on July 12, 1862. Is it mere coincidence that the very next day he penned the preliminary EP with which he surprised Seward and Welles later that evening? The meeting on July 12 was with border State congressmen of whom seven three days later formalized in a letter to Lincoln the info they had shared in their meeting with their President:

“We are the more emboldened to assume this position from the fact, now become history, that the leaders of the Southern rebellion have offered to abolish slavery amongst them as a condition to foreign intervention in favor of their independence as a nation. If they can give up slavery to destroy the Union; We can surely ask our people to consider the question of Emancipation to save the Union.”

This CS offer to end slavery is corroborated by several foreign news sources as early as April 8, 1862.

***************************

“Brannigan was white-hot with hatred for the Southern aristocrats who had led the secession movement as well as for native-born New Yorkers who failed to enlist in the army to save their country.”

A typical tenet of the modern mythical narrative is that slave-holding “aristocrats” somehow coerced the Southern polity to secede. Just the reverse was true. It was the Southern people, 75% non-slave holding, who pressured their duly elected leaders to secede, and who voted in State conventions for secession.

***************************

“While he said that the South was being punished for its ‘injustice’ towards blacks, he warned that there ‘is no reason why we should go to the other extreme.’”

An end-goal that lacks a moral means and moral intent lacks any moral merit. To be “anti-slavery” in such an abstract way, without a true interest in the well-being and equality of the slave, only serves ones own virtue-seeking selfish purpose. As even Lincoln realized, “What then free them all and keep them among us as underlings? Is it quite certain that this betters their condition?” To be Anti-slavery in the abstract, while holding a racist opinion of black people, is abstract moralizing of the worst kind! And it led directly to the impossible corner into which the North had backed the South. Given the North was determined to keep non-resident blacks out of their States and the territories, freed slaves had no where to be dispersed to avoid the humanitarian disaster that would result from attempting to accommodate them as freedmen within Southern borders alone. The North simply refused to acknowledge and take responsibility for its foundational role and continuing involvement in the institution of Southern slavery. Had it been willing to share in the social and economic sacrifice that its role in slavery justified, a national plan of emancipation and integration would have made the emancipation momentum in the South in the early 19th century bear fruit. Instead, Northern racism sought to make the South endure all the sacrifice that emancipation would require.

********************************************

“…it occupied Charleston, South Carolina, the city where the Civil War had begun with the attack on Fort Sumter in 1861.”

The war began when Lincoln sent ships into the territorial waters of a sovereign State. These ships were sent to resupply a fort that, by the violation of the terms of the existing contract under which it was being constructed, had reverted back to ownership of South Carolina.

***************************

“The army had not allowed black men to enlist in large numbers until 1863. When they were finally admitted to service they were placed in segregated regiments in which all the enlisted men were Black and all of the officers were white.”

Interesting to note that a full year before Lincoln begrudgingly allowed blacks to serve in segregated units in the Union Army, the State of Tennessee passed legislation in its General Assembly on June 28, 1861 allowing “all male free persons of color between the ages of fifteen and fifty” to serve integrated in its State regiments. This law in no manner debarred them the use of arms.

***************************

“ Its mission, in the first few months after the war, was to liberate blacks still held as slaves two and a half years after Emancipation and guard against guerrilla activity by whites hoping to reestablish control over the black population… Brannigan served in the United States Attorney’s office in Mississippi at a time when the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups were assassinating anyone who defended the rights of African Americans.”

Here again is another tenet of the Righteous Cause Myth which views reconstruction through the lens of Marxist style analysis. Many slaves wanted to remain with their masters, and Southern “guerrilla activity” had far more to do with opposition to Republican tyranny than it did any desire to “control blacks.” Republicans were deliberately attempting to destroy the bond between former masters and slaves in order to use the freedmen as political pawns of Republican power. The original KKK recruited blacks and included them in a sentiment of solidarity against yankees who sought to rule their Southland. For a true evaluation of what was going on in the South, read the writings of Booker T. Washington on the real motives in Reconstruction. Read the letter of the first black senator, Hiram Rhodes Revels, written to President Grant regarding the shenanigans of the Republican Party which deliberately created racial tensions, “ The bitterness and hate created by the late civil strife would have long since been entirely obliterated were it not for some unprincipled men who would keep alive the bitterness of the past and inculcate a hatred between the races, in order that they may aggrandize themselves by office and its emoluments to control my people, the effect of which is to degrade them.”

Typical of most modern historians, whose presumptions are based more on nationalist bias or Leftist political agenda than historical facts, this article needs balance.

The article describes Brannigan’s perspective, not your’s.

The article describes a modern interpretation of Brannigan’s perspective, with little reference to the realities of his world which are very likely to have been important to his actual perspective.

It’s hard for me to believe that anyone could seriously believe the Confederate government was considering emancipating all the slaves in mid-1862.

It’s just too bizarre. Where is the evidence? Not foreign newspapers. Not a deluded border-stater. The actual evidence that Confederate leadership was considering emancipation in mid-1862. Where is it?

Dan If you read Rod B O’Barr’s comment, he gives substantial direct evidence of these negotiations. Also, see “Slavery, Secession, & Civil War”, Charles Adams, p. 304, from a British journal “Once A Week” set up in contradiction to Dickens’ fiscal view of the war. To be clear, the Confederacy was discussing emancipation, not necessarily planning on effecting it in 1862. But since their primary goal was direct trade with Europe, free from Northern tariffs, with the significant economic benefit of that situation, they clearly were aware that European trading partners wanted emancipation and were willing to go that route. That’s the same reason Brazil began its emancipation program in 1871.

Foreign journalists were not making decisions on emancipation in the confederacy. Where is the evidence that the confederate leadership was considering emancipation in 1862?

Carson Foard claims that Rod O’Barr “gives substantial direct evidence” of negotiations by the Confederacy involving the ending of slavery. He actually offers no direct evidence at all.

“To be Anti-slavery in the abstract, while holding a racist opinion of black people, is abstract moralizing of the worst kind!”

This is a silly assertion. As if being racist is morally worse than being an enslaver.

Rod and Carson are throwing the spaghetti against the wall to see what sticks. I won’t try to counter each of the many strands of spaghetti they threw, since it all comes from the same pot, to wit, in Rob’s words:

_____

Many slaves wanted to remain with their masters, and Southern “guerrilla activity” had far more to do with opposition to Republican tyranny than it did any desire to “control blacks.” Republicans were deliberately attempting to destroy the bond between former masters and slaves in order to use the freedmen as political pawns of Republican power. The original KKK recruited blacks and included them in a sentiment of solidarity against yankees who sought to rule their Southland.

_____

Even when they want to appear to be objective they always fall back on Lost Cause tropes of loyal slaves and a benevolent Ku Klux Klan. This fools no one guys.

Rod and Carson are correct in their analysis and it doesn’t take much study to determine what they wrote here is absolutely correct. Your spaghetti analogy doesn’t pass the snuff test.

Kev, there is zero evidence that the Confederacy offered to end slavery in order to gain foreign support. The contention that slaves wanted to stay with their masters, and that the Ku Klux Klan was a biracial movement struggling for freedom is all stuff and nonsense.

Amongst those “spaghetti strings”, known to some as solid research, is proof that the Confederacy was discussing ending slavery to gain foreign support. It’s up there in print. All the letters and documents mentioned exist in real time, as do the publications mentioning it, especially European papers (see my note on “Slavery, Secession, & Civil War”, C. Adams, p. 304, just one piece of evidence). If you won’t read comments giving you documentation on a point you dont want to concede, it’s worrisome that this is a site dedicated to the education of the young. All the other points are drawn from specific evidence proving the points, including contemporary accounts, both personal and public (letters and newspapers, etc.) that is available to anyone willing to do the research, or at least read the comments of others who have. Rigidity in thinking is not a preferred hallmark of the academic mind.

Here’s where this fantasy of confederate emancipation in 1862 originates. The American diplomat writes to Washington about something he read in a Scottish newspaper:

“My main purpose in alluding to it is to call your attention to a singular development made of the policy adopted by the Confederate emissaries here with a view to fortify the movement of their allies in this country. The substance of it has been disclosed by a publication in the Edinburg Scotsman, a well-conducted paper whose sources of information I have heretofore found to be good. I take from its issue on Saturday last, the 11th of January, the following extract:

There exist in London an active and growing party including many members of Parliament having for its object an immediate recognition of the Southern Confederacy on certain understood terms. This party is in communication with the quasi representatives of the South in London and gives out that it seems its was to a desirable arrangement. Our information is that the South acting through its London agents is at least willing to have it understood that in consideration of immediate recognition and the disregard of the paper blockade it would engage for these three things: A treaty of free trade, the prohibition of all import of slaves, and the freedom of all blacks born hereafter. It will easily be seen that if any such terms were offered (but we hesitate to believe that last of them) a pressure in favor of the South will come upon the British Government from more than one formidable section of our public.

I have reason for believing that some such project as this has been actually entertained by the Confederate emissaries. The pressure of the popular feeling against slavery is so great here that their friends feel it impossible to hope to stem it without some such plea in extenuation as can be made out of an offer to do something for ultimate emancipation.

Of course no man acquainted with the true state of things in America can believe for an instant the existence of one particle of good faith in any profession of thinks kind that may be countenanced by the rebel emissaries here. But I have thought it might not be without its use to recommend that the fact of their sanction of such an agitation should be made know pretty generally in the United States especially among the large class of the friends of the Union in the border States.

If the issue of this contest is to be emancipation with the aid of Great Britain surely the object rebellion against our Government was initiated-the protection and perpetuation of slavery-ceases to be a motive for resisting it further.

If the course of the emissaries here be unauthorized it ought to be exposed here to destroy all further confidence in them. If on the contrary if be authorized it should be equally exposed to the people in the slave-holding States. In either event the eyes of he people both in Europe and America will be more effectually opened to a conviction of the nature and certain consequence of this great struggle.”

So Adams believes that either the newspaper is wrong, or the confederate emissaries are unauthorized to offer that concession, and are in effect, lying in order to get foreign support.

So again, show where the Confederate government, the actual Confederate leadership, EVER proposed emancipation in 1862. It’s nothing but a fantasy.

I should add, the American diplomat is Charles Francis Adams.

Thanks for the info Dan.