US Government Financing of the Civil War

ECW welcomes guest author Dr. Lloyd W. Klein

Faced with the problem of financing a major war, President Abraham Lincoln and his Treasury Secretary, Salmon P. Chase, found innovative solutions that remain foundational of the contemporary US economy. Some of these measures set precedents for war financing. Few Americans realize the historical background of these solutions. President Lincoln left most decisions to his Treasury secretary and Chase’s successors. They worked successfully to ensure the Union had the money it needed to win the war.

The total cost of the Civil War was staggering, and the increment in expenditures compared to the ante bellum economy astonishing. In the 1850s, federal expenditures averaged roughly $1 million a week. In comparison, by mid-1861, the cost of conducting the war alone was $1.5 million a day. Before the war ended, war expenditures had increased to $3.5 million a day, and the US became the first government to spend more than $1 billion in a single year. The total cost of the war has been estimated to be $68.17 billion in 2019 dollars. By comparison World War II cost $4.69 trillion.

War Bonds

Financing the Civil War was achieved through a combination of new revenue from higher tariffs, proceeds from loans and bond sales, taxes on incomes, and issuance of paper money not backed by silver or gold (“greenbacks”). At the start of the war, with patriotism strong, millions of dollars in bonds and notes were sold to the public, a forerunner of the bond drives of the World Wars.

The federal government had great difficulty raising money abroad, so the bonds and loans were largely domestic. It was beneficial that gold was being mined in California, which could be minted into coins to support the convertibility of federal notes.

Chase reported to Congress In summer 1861 that $320 million over the next fiscal year would be needed to finance the war. He thought he could raise $300 million by borrowing, raising existing taxes and from the sale of public lands. It was up to Congress to raise the remaining $20 million.

On July 17, 1861, Congress enabled the Treasury to borrow as much as $250 million for the war effort by issuing bonds and notes. The idea was to sell these to a wide range of investors, including small-business owners and families. By buying their government’s “paper”, Americans showed their support for the war effort. One of these securities was a “bearer instrument”: the holder received the principal due from the Treasury. Other bonds were “coupon bonds”: the holder received interest payments by clipping off and remitting a small portion at the bottom when due, called the coupon. There were also bonds registered in the bond owner’s name and interest was credited when due. Bearer securities were the most easily traded, while registered debt was the most secure. “Seven-Thirties” were notes that matured in three years and paid investors 7.30% interest per year. “Five-Twenties” were bonds that matured in 20 years but were redeemable after only five years, paying 6% interest. “Ten-Forties” were bonds that matured in 40 years; they were redeemable after 10 years if the government consented. Some of these bonds paid 6% and others 5% annual interest.

Paper Currency

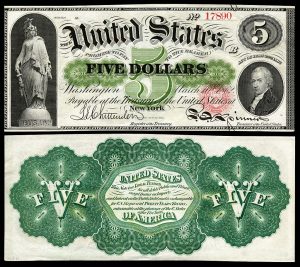

The most historically and economically significant bonds were notes that bore no interest but were payable on demand, and hence called “Demand Notes”. These bonds could be exchanged for coin at any time at one of the Treasury’s branches. The Demand Notes were redeemable in coin “on demand.” The notes were nicknamed “Greenbacks” because of their distinctive green ink on their reverse, a name still in use to refer to United States currency. These bonds were issued in small denominations ($5, $10 and $20), which meant they could circulate as money; they were the first successful federal paper currency. These bills were issued between August 1861 and April 1862.

By 1862, the government was having trouble funding the escalating war. U.S. Demand Notes became increasingly unredeemable, and the value of the notes began to deteriorate. Congressman and Buffalo banker Elbridge G. Spaulding introduced a bill to permit the Treasury to issue $150 million in notes as “legal tender”. This caused tremendous Congressional controversy because the Constitution was interpreted to indicate that the Federal government was not granted the power to issue paper currency. The term “legal tender” guaranteed that creditors would accept the notes even though they were not backed by gold, bank deposits, or government reserves, and offered no interest. The first $1 bill was issued in 1862 as a Legal Tender Note. It was designed with a portrait of Chase on the front.

The National Banking Act of 1863 established a uniform national currency and national federal banks. National Banks were required to purchase U.S. government securities as backing for what were termed “National Bank Notes”. The government chartered national banks to hold bonds and issue federal notes, which were issued in small denominations that could serve as currency, along with the “greenbacks”. Most of the paper currency that circulated from 1863 to 1932 was called a “National Bank Note”, which were printed by private companies from 1863 to 1877. The Federal government began printing them in 1877, backed by US Bonds deposited in the US Treasury. National banks were required to maintain a fund amounting to 5% of outstanding balance.

Gold certificates, which were paper money backed by gold reserves, were first issued in 1863 and put into general circulation in 1865. The Gold Certificate was circulated until 1933; each bill gave its holder title to a matching amount of gold coin at the rate of $20.67 per troy ounce. This paper currency was intentionally proffered as representing actual gold coinage.

By issuing notes of small value that could be traded for goods and services, Chase had created a federal paper currency to cover government debt. Like most, he anticipated that the war would be brief and he believed his measures were temporary, to fund the war, and would be promptly abandoned once the war was over. He did not suspect that his idea of Demand Notes would, in time, completely transform the circulating money that ordinary citizens used.

Personal Income Tax

The Revenue Act of 1861 was passed to increase import tariffs, property taxes, and for the first time, to levy a flat rate income tax of 3% on incomes above $800. Its drawback was that it lacked a comprehensive enforcement mechanism. Thaddeus Stevens, chairman of the House Committee of Ways and Means Committee, avowed, “This bill is a most unpleasant one. But we perceive no way in which we can avoid it and sustain the government. The rebels, who are now destroying or attempting to destroy this Government, have thrust upon the country many disagreeable things.”

In 1862, President Lincoln signed a law imposing a graduated income tax. The law levied a 3% tax on incomes between $600 and $10,000 and a 5% tax on higher incomes. The law was later amended in 1864; it levied a 5% tax on incomes between $600 and $5,000, a 7.5% tax on incomes in the $5,000-$10,000 range and a 10% tax on all higher incomes. The income tax was declared unconstitutional in 1872, but returned in 1909 with the 16th amendment.

The Confederacy also attempted to institute an income tax. It authorized a national graduated income tax in 1863. The tax exempted up to $1,000, levied a 1% tax on the first $1,500 over the exemption, and 2% on all additional income. The Confederate income tax failed to raise sufficient funds because as the war continued, domestic production and agriculture halted, so there was diminishing income to tax. Confederate financial efforts failed as their military fortunes waned and a growing deficit and hyper-inflation made it difficult to sell bonds and support the war effort. In contradistinction, there was no major inflation of federal money during the war.

Dr. Lloyd W. Klein is Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco. He is a nationally recognized cardiologist with over thirty-five years’ experience and expertise. He is also an amateur historian who has read extensively and published previously on the Civil War, with a particular interest in political and military leadership and their economic ramifications.

References

- A Brief History of US Government Currency 1861-present. https://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Pages/US-Currency-Brief-History-Part-1.aspx

- Financing the Civil War by Michael A Martorelli. https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/financing-the-civil-war.html

- Funding the Civil War with an Income Tax by Adam David Gibbons. https://www.americanheritage.com/content/funding-civil-war

It was either Talleyrand or Metternich who said “the revenue of the state is the state.” Thank you for this article.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

I don’t believe the income tax was ruled unconstitutional in 1872. It was repealed. The USSC in Springer v United States (1880) , Justice Swayne delivering the opinion, determined that the income tax was not a direct tax subject to apportionment and hence was not unconstitutional as imposed by the act of 1864. But this decision was modified after the new income tax was imposed by the case of Pollack v Farmers’ Loan and Trust Co (1895), the opinion given by Chief Justice Fuller on a close 5-4 decision. Pollack ruled that you had to look to the source of the income to determine if the tax was direct and had to follow the rule of apportionment. That of course was resolved by Amend. XVI that declared taxes on income were not subject to the rule of apportionment regardless of source (and hence subject to the rule of uniformity).

On financing the Union war effort, there are some biographies on Jay Gould who was instrumental in putting together the actual bond sales for Chase (and managed to enrich himself in the process).

Gould though, after the war, fell in love with the idea that a transcontinental railroad was needed terminating at Duluth MN, which he believed could become a major port. Since railroads were capital intense, it was natural that bankers would be drawn to them. In my estimation Gould lacked the ability to procure the engineering talent needed to pull off the Northern Pacific RR. It ended up bankrupting him and plunged the US into financial panic yet again (similar to that resulting from the Credit Mobilier). The northern route would later be achieved by James Hill’s Great Northern as I think Hill did have the engineering know-how.

You are correct. Thank you for the comment. The income tax authorization was repealed in 1872.The 1894 Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act contained an income tax provision, and this was the tax declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in the case of Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co. In its ruling, the Supreme Court did not hold that all federal income taxes were unconstitutional, but rather held that income taxes on rents, dividends, and interest were direct taxes and thus had to be apportioned among the states on the basis of population.

The financing of the Northern war effort was monumental; and Salmon P. Chase was instrumental in making it happen. For the South, it appears that cotton (and perhaps other commodities) were “sold forward” and loans taken out overseas in order to generate the required funding.

Thanks for introducing this too-long ignored topic.

Thank you for reading and for the comment. Later this week I will post about the Southern economic challenges during the war.

Excellent. As it appears that “economic warfare” was practiced by the Lincoln Administration taking possession (confiscation) of Southern cotton, beginning about 1862, for delivery to Northern mills and overseas mills. And this confiscation would 1) deny Southern collateral for overseas loans, and 2) help defuse any British tendency to increase support for the Confederate States of America.

Again, Thanks for revealing that there were a lot more layers to the Civil War than at first appear…

I also just remembered… early in the conflict, about August or September 1861 there was a “race for bank deposits” in regional Missouri. Both sides stated they were “removing those deposits for safe keeping…” the Union sequestered the cash and reserves in Federal-controlled St. Louis; and the Rebels wagon-trained their withdrawals away, further south [see https://mospace.umsystem.edu/xmlui/handle/10355/4423 ]

Thank you for this article and thank you editors for seeing the wisdom of adding it to the honor roll of articles that get posted here. A topic not as popular as Bloody Angle or Bloody Lane, but the government had to get a pound of flesh from somewhere to pay for among other things, enlistment bonuses.

Thank you for reading and for your comment.

Excellent piece. Is there a book in our future?

Thanks for reading and for your comment. Well, maybe. I want to gauge what interest there is in this and some other pieces I will submit here.

Great post! This is the most vital yet overlooked aspect of the war.

Without these efforts, victory might not have been possible.

As someone famously once said, “ follow the money.”

I appreciate your interest!

Thanks for a most interesting post! Hanging on the wall over my desk is a CSA coupon bond, issued in September, 1862. It is a $50, 8% per annum interest, maturing July 1, 1874. There are quite a few coupons still attached. In today’s dollars, $50 would be $1345 — a 2.09% cumulative average inflation rate. The annual interest would be $107.60 in today’s money. Sure would be nice to be able to buy an 8% bond today!

Thanks for reading my post and for your comment. That would be a wonderful piece of memorabilia to own. I suspect its value is far more than its face.

Another way to look at the war! Huzzah! Just fascinating–I look forward to the next one.

Meg, did you get the new Walt Whitman postage stamp? It is not a regular stamp, it costs 85 cents per stamp.

Was liquor taxed at some point? I read elsewherw that distilled liquor was taxed a $1/gallon, but beer was taxed at only a $1/barrel. Can you verify, thanks.